Authors: Madison Smartt Bell

Tags: #Social Science, #Caribbean & West Indies, #Slavery, #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #Slave insurrections, #Haiti, #General, #History

All Souls' Rising

Contents

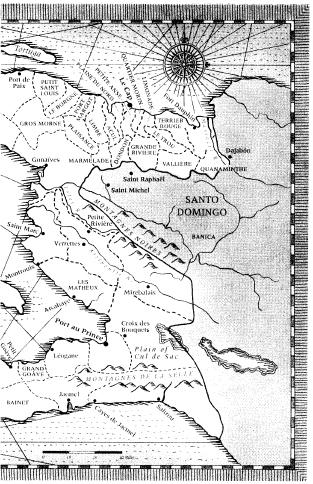

Map of Saint Domingue in the Late Eighteenth Century

(August 1791)

(August—November 1791)

(November 1791—April 1792)

(August 1792—June 1793)

Also by Madison Smartt Bell: Master of the Crossroads

Preview of The Stone That the Builder Refused

For les Morts et les Mystères,

and for all souls bound in living bodies,

I have burned this offering

Four hundred years

…

(Four hundred years, four hundred years…)

And it’s the same

…

Same philosophy

…

B

OB

M

ARLEY

Acknowledgments

This novel was completed with invaluable assistance from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the George A. and Eliza Gardner Howard Foundation, the Maryland State Arts Council, and the National Endowment for the Arts. My thanks also to George Garrett and Russell Banks for good advice and good examples, and to Isabel Reinharez, Caroline Gifford, Tom McGonigle, Cassandra Dunwell, Thomasin LaMay of the Goucher College Library, Caroline Smith of Special Collections at the Johns Hopkins University Libraries, Jennifer Bryan of the Manuscripts Division of the Maryland Historical Society, Daryl Phillip of the Cane Mill Museum of Dominica, and M. Emmanuel Leroy Ladurie of the

Bibliothèque nationale

in Paris, for their critical research assistance—may fortune smile upon you all.

Preface

I

N

1791,

THE COLONY OF

S

AINT

D

OMINGUE

, established on the western half of the island which Columbus had named Hispaniola and which the native Amerindians (before their wholesale extermination by the Spanish) had called Hayti, was the richest and most productive French possession overseas, known as the Jewel of the Antilles. Plantations in the colony, run by slave labor, produced fortunes in sugar and coffee, which could create for their proprietors, who were frequently absentees, luxurious lives in Paris. From the point of view of French landowners, locally known as

grand blancs

, Saint Domingue was not a place to settle permanently but a place to get rich quick.

The shock of the French Revolution in 1789 traveled along social and racial fault lines already present in the colony. The

grand blanc

landowners, who owned most of the plantations and most of the slaves, were conservative and royalist by disposition and for the most part unfriendly to French Revolutionary radical ideas. By 1791 the idea was already afoot in this group that at worst the colony might splinter off from the home government and reconstitute itself as a royalist refuge or perhaps make itself a protectorate of the British (who maintained slavery in Jamaica and their other Caribbean colonies). The

grand blanc

royalists in the colony identified themselves by wearing a white cockade and were therefore sometimes known as

Pompons Blancs

.

Meanwhile there existed a lower class of white people in the colony, an artisan class mostly concentrated in the two principal cities of the coast: Cap Français (commonly known as Le Cap) in the north and Port-au-Prince in the western department. Members of this group were not necessarily French in origin; they were an obscure and shifting community, including a great many professional criminals, adventurers, and international fugitives. Some originated from an earlier period when the island had been a haven and stronghold of pirates. These

petit blancs

, who embraced French Revolutionary ideas, were at odds with the

grand blanc

landowners, and between 1789 and 1791 the struggle between these two groups for political control of the colony sometimes came to violence. The

petit blanc

revolutionaries distinguished themselves by wearing a red cockade and were known for this reason as

Pompons Rouges

. Their declared loyalty to the French Revolutionary government led them to call themselves Patriots.

Whatever their differences among themselves, white people were in a minority in Saint Domingue. In 1791 there were about thirty-nine thousand white people in the colony, twenty-seven thousand people of mixed blood, and four hundred and fifty-two thousand black slaves. The large mulatto population, descendants of white landowners and black slaves, had come into being because there had never been many white women in the colony, which had always attracted opportunists and entrepreneurs rather than settlers proper. Some mulattoes were enslaved but many were free, and there existed a class of freedmen, or

affranchis

, who were mostly of mixed race, though some full-blooded blacks were also included.

Sixty-four different shades of color were identified (and named) among the mulattoes, and social status depended on the lightness of the shade. Economically, the mulattoes were a powerful group. Many were wealthy and owned land and slaves of their own, and many had been well educated—sometimes in France. But the mulattoes had no political rights whatsoever. Though required to serve three years in the militia, they could not vote or hold office—only white people played any part in the political life of the colony. Apart from a lively business in prostitution, mulattoes had little social contact with whites, were forced to give precedence to whites in all circumstances, and were sometimes victims of spontaneous genocidal pogroms.

There was a special animosity between the mulattoes, who had wealth but no political rights, and the

petit blancs

, who had rights but little money. These tensions were exacerbated after 1789, when the mulattoes began sending delegations to Paris to petition for political equality and voting rights. These delegations found sympathy among the more radical French Revolutionary factions and among abolitionist organizations like

Les Amis des Noirs

. But in the early phases of the French Revolution, the parties in power believed very firmly that the Rights of Man must apply to white men only. Saint Domingue was one of the few sectors of the French economy still functioning after the Revolution; therefore slavery and the racial hierarchy underwritten by the slave system had to be maintained.

As for the tremendous number of black slaves, only a minority were Creole (a term designating anyone of any race who was born in the colony). In part because absentee ownership was so common, abuses and cruelty were much more frequent and severe in Saint Domingue than in the southern United States or in most other slaveholding societies. Through suicide, infanticide, abortion, starvation, neglect, overwork, and murder, the black slaves of Saint Domingue died off at a much faster rate than they could replace themselves by new births. It was necessary for the proprietors to import twenty thousand fresh slaves from Africa

annually

in order to maintain the workforce at a constant level.

Thus a two-thirds majority of the slaves in the colony had been born in Africa. They came from ten or twelve different tribes and spoke as many different languages. They communicated with their masters and with one another in a patois with French vocabulary and African syntax; this language, also called Creole, is still spoken in Haiti today. The slave population synthesized a variety of different African religious traditions into a common religion called vodoun or voodoo, which was universal among the African slaves and very common among the Creole slaves also—including those Creole slaves who were nominally Christian. Vodoun, which includes a pantheon of gods who take literal and physical possession of their worshipers, incorporated components of African ancestor worship with a new mythology evolved on slave ships. Practitioners believed that Africa, or Guinée, existed as an island below the sea and that death was the portal of return to Africa.

Occupied with their quarrels among themselves, the whites of Saint Domingue gave little thought to the possible effects of the French Revolution on the mulattoes and almost none at all to its possible effects on the black slaves. Because of their common economic interests, some queasy and unstable alliances did form between

grand blancs

and mulattoes. The blacks, who were not generally acknowledged to be fully human, were ignored. Meanwhile, Revolutionary conceptions like “the Rights of Man” circulated freely and noisily through the entire colony and were as audible to the black slaves as to anyone.