Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) (432 page)

Read Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) Online

Authors: JOSEPH CONRAD

I am no lover of day-breaks. You know how thin, equivocal, is the light of the dawn. But she was now her true self, she was like a fine tranquil afternoon — and not so very far advanced either. A woman not much over thirty, with a dazzling complexion and a little colour, a lot of hair, a smooth brow, a fine chin, and only the eyes of the Flora of the old days, absolutely unchanged.

In the room into which she led me we found a Miss Somebody — I didn’t catch the name, — an unobtrusive, even an indistinct, middle-aged person in black. A companion. All very proper. She came and went and even sat down at times in the room, but a little apart, with some sewing. By the time she had brought in a lighted lamp I had heard all the details which really matter in this story. Between me and her who was once Flora de Barral the conversation was not likely to keep strictly to the weather.

The lamp had a rosy shade; and its glow wreathed her in perpetual blushes, made her appear wonderfully young as she sat before me in a deep, high-backed arm-chair. I asked:

“Tell me what is it you said in that famous letter which so upset Mrs. Fyne, and caused little Fyne to interfere in this offensive manner?”

“It was simply crude,” she said earnestly. “I was feeling reckless and I wrote recklessly. I knew she would disapprove and I wrote foolishly. It was the echo of her own stupid talk. I said that I did not love her brother but that I had no scruples whatever in marrying him.”

She paused, hesitating, then with a shy half-laugh:

“I really believed I was selling myself, Mr. Marlow. And I was proud of it. What I suffered afterwards I couldn’t tell you; because I only discovered my love for my poor Roderick through agonies of rage and humiliation. I came to suspect him of despising me; but I could not put it to the test because of my father. Oh! I would not have been too proud. But I had to spare poor papa’s feelings. Roderick was perfect, but I felt as though I were on the rack and not allowed even to cry out. Papa’s prejudice against Roderick was my greatest grief. It was distracting. It frightened me. Oh! I have been miserable! That night when my poor father died suddenly I am certain they had some sort of discussion, about me. But I did not want to hold out any longer against my own heart! I could not.”

She stopped short, then impulsively:

“Truth will out, Mr. Marlow.”

“Yes,” I said.

She went on musingly.

“Sorrow and happiness were mingled at first like darkness and light. For months I lived in a dusk of feelings. But it was quiet. It was warm . . . “

Again she paused, then going back in her thoughts. “No! There was no harm in that letter. It was simply foolish. What did I know of life then? Nothing. But Mrs. Fyne ought to have known better. She wrote a letter to her brother, a little later. Years afterwards Roderick allowed me to glance at it. I found in it this sentence: ‘For years I tried to make a friend of that girl; but I warn you once more that she has the nature of a heartless adventuress . . . ‘ Adventuress!” repeated Flora slowly. “So be it. I have had a fine adventure.”

“It was fine, then,” I said interested.

“The finest in the world! Only think! I loved and I was loved, untroubled, at peace, without remorse, without fear. All the world, all life were transformed for me. And how much I have seen! How good people were to me! Roderick was so much liked everywhere. Yes, I have known kindness and safety. The most familiar things appeared lighted up with a new light, clothed with a loveliness I had never suspected. The sea itself! . . . You are a sailor. You have lived your life on it. But do you know how beautiful it is, how strong, how charming, how friendly, how mighty . . . “

I listened amazed and touched. She was silent only a little while.

“It was too good to last. But nothing can rob me of it now . . . Don’t think that I repine. I am not even sad now. Yes, I have been happy. But I remember also the time when I was unhappy beyond endurance, beyond desperation. Yes. You remember that. And later on, too. There was a time on board the Ferndale when the only moments of relief I knew were when I made Mr. Powell talk to me a little on the poop. You like him? — Don’t you?”

“Excellent fellow,” I said warmly. “You see him often?”

“Of course. I hardly know another soul in the world. I am alone. And he has plenty of time on his hands. His aunt died a few years ago. He’s doing nothing, I believe.”

“He is fond of the sea,” I remarked. “He loves it.”

“He seems to have given it up,” she murmured.

“I wonder why?”

She remained silent. “Perhaps it is because he loves something else better,” I went on. “Come, Mrs. Anthony, don’t let me carry away from here the idea that you are a selfish person, hugging the memory of your past happiness, like a rich man his treasure, forgetting the poor at the gate.”

I rose to go, for it was getting late. She got up in some agitation and went out with me into the fragrant darkness of the garden. She detained my hand for a moment and then in the very voice of the Flora of old days, with the exact intonation, showing the old mistrust, the old doubt of herself, the old scar of the blow received in childhood, pathetic and funny, she murmured, “Do you think it possible that he should care for me?”

“Just ask him yourself. You are brave.”

“Oh, I am brave enough,” she said with a sigh.

“Then do. For if you don’t you will be wronging that patient man cruelly.”

I departed leaving her dumb. Next day, seeing Powell making preparations to go ashore, I asked him to give my regards to Mrs. Anthony. He promised he would.

“Listen, Powell,” I said. “We got to know each other by chance?”

“Oh, quite!” he admitted, adjusting his hat.

“And the science of life consists in seizing every chance that presents itself,” I pursued. “Do you believe that?”

“Gospel truth,” he declared innocently.

“Well, don’t forget it.”

“Oh, I! I don’t expect now anything to present itself,” he said, jumping ashore.

He didn’t turn up at high water. I set my sail and just as I had cast off from the bank, round the black barn, in the dusk, two figures appeared and stood silent, indistinct.

“Is that you, Powell?” I hailed.

“And Mrs. Anthony,” his voice came impressively through the silence of the great marsh. “I am not sailing to-night. I have to see Mrs. Anthony home.”

“Then I must even go alone,” I cried.

Flora’s voice wished me “bon voyage” in a most friendly but tremulous tone.

“You shall hear from me before long,” shouted Powell, suddenly, just as my boat had cleared the mouth of the creek.

“This was yesterday,” added Marlow, lolling in the arm-chair lazily. “I haven’t heard yet; but I expect to hear any moment . . . What on earth are you grinning at in this sarcastic manner? I am not afraid of going to church with a friend. Hang it all, for all my belief in Chance I am not exactly a pagan . . . “

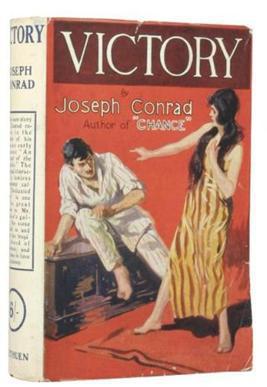

VICTORY

AN ISLAND TALE

This novel was first published in 1915, receiving mixed critical reviews. It features a shifting narrative and temporal perspective, with different viewpoints from different characters, as well as an omniscient narrator.

Victory

tells the story of Axel Heyst, who ends up living on an island in Indonesia, after a business misadventure. Heyst visits a nearby island when a female band is playing at a hotel owned by Mr. Schomberg. Who attempts to rape one of the band members. She flees with Heyst back to his island and they become lovers.

The first edition

CONTENTS

AUTHOR’S NOTE

On approaching the task of writing this Note for Victory, the first thing I am conscious of is the actual nearness of the book, its nearness to me personally, to the vanished mood in which it was written, and to the mixed feelings aroused by the critical notices the book obtained when first published almost exactly a year after the beginning of the war. The writing of it was finished in 1914 long before the murder of an Austrian Archduke sounded the first note of warning for a world already full of doubts and fears.

The contemporaneous very short Author’s Note which is preserved in this edition bears sufficient witness to the feelings with which I consented to the publication of the book. The fact of the book having been published in the United States early in the year made it difficult to delay its appearance in England any longer. It came out in the thirteenth month of the war, and my conscience was troubled by the awful incongruity of throwing this bit of imagined drama into the welter of reality, tragic enough in all conscience, but even more cruel than tragic and more inspiring than cruel. It seemed awfully presumptuous to think there would be eyes to spare for those pages in a community which in the crash of the big guns and in the din of brave words expressing the truth of an indomitable faith could not but feel the edge of a sharp knife at its throat.

The unchanging Man of history is wonderfully adaptable both by his power of endurance and in his capacity for detachment. The fact seems to be that the play of his destiny is too great for his fears and too mysterious for his understanding. Were the trump of the Last Judgement to sound suddenly on a working day the musician at his piano would go on with his performance of Beethoven’s sonata and the cobbler at his stall stick to his last in undisturbed confidence in the virtues of the leather. And with perfect propriety. For what are we to let ourselves be disturbed by an angel’s vengeful music too mighty for our ears and too awful for our terrors? Thus it happens to us to be struck suddenly by the lightning of wrath. The reader will go on reading if the book pleases him and the critic will go on criticizing with that faculty of detachment born perhaps from a sense of infinite littleness and which is yet the only faculty that seems to assimilate man to the immortal gods.

It is only when the catastrophe matches the natural obscurity of our fate that even the best representative of the race is liable to lose his detachment. It is very obvious that on the arrival of the gentlemanly Mr. Jones, the single-minded Ricardo, and the faithful Pedro, Heyst, the man of universal detachment, loses his mental self-possession, that fine attitude before the universally irremediable which wears the name of stoicism. It is all a matter of proportion. There should have been a remedy for that sort of thing. And yet there is no remedy. Behind this minute instance of life’s hazards Heyst sees the power of blind destiny. Besides, Heyst in his fine detachment had lost the habit of asserting himself. I don’t mean the courage of self-assertion, either moral or physical, but the mere way of it, the trick of the thing, the readiness of mind and the turn of the hand that come without reflection and lead the man to excellence in life, in art, in crime, in virtue, and, for the matter of that, even in love. Thinking is the great enemy of perfection. The habit of profound reflection, I am compelled to say, is the most pernicious of all the habits formed by the civilized man.