Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (30 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

CHAPTER XIX.

Oxford. — Montmorency’s idea of Heaven. — The hired up-river boat, its beauties and advantages. — The “Pride of the Thames.” — The weather changes. — The river under different aspects. — Not a cheerful evening. — Yearnings for the unattainable. — The cheery chat goes round. — George performs upon the banjo. — A mournful melody. — Another wet day. — Flight. — A little supper and a toast.

We spent two very pleasant days at Oxford. There are plenty of dogs in the town of Oxford. Montmorency had eleven fights on the first day, and fourteen on the second, and evidently thought he had got to heaven.

Among folk too constitutionally weak, or too constitutionally lazy, whichever it may be, to relish up-stream work, it is a common practice to get a boat at Oxford, and row down. For the energetic, however, the up-stream journey is certainly to be preferred. It does not seem good to be always going with the current. There is more satisfaction in squaring one’s back, and fighting against it, and winning one’s way forward in spite of it — at least, so I feel, when Harris and George are sculling and I am steering.

To those who do contemplate making Oxford their starting-place, I would say, take your own boat — unless, of course, you can take someone else’s without any possible danger of being found out. The boats that, as a rule, are let for hire on the Thames above Marlow, are very good boats. They are fairly water-tight; and so long as they are handled with care, they rarely come to pieces, or sink. There are places in them to sit down on, and they are complete with all the necessary arrangements — or nearly all — to enable you to row them and steer them.

But they are not ornamental. The boat you hire up the river above Marlow is not the sort of boat in which you can flash about and give yourself airs. The hired up-river boat very soon puts a stop to any nonsense of that sort on the part of its occupants. That is its chief — one may say, its only recommendation.

The man in the hired up-river boat is modest and retiring. He likes to keep on the shady side, underneath the trees, and to do most of his travelling early in the morning or late at night, when there are not many people about on the river to look at him.

When the man in the hired up-river boat sees anyone he knows, he gets out on to the bank, and hides behind a tree.

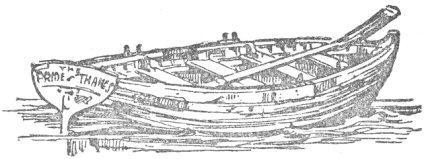

I was one of a party who hired an up-river boat one summer, for a few days’ trip. We had none of us ever seen the hired up-river boat before; and we did not know what it was when we did see it.

We had written for a boat — a double sculling skiff; and when we went down with our bags to the yard, and gave our names, the man said:

“Oh, yes; you’re the party that wrote for a double sculling skiff. It’s all right. Jim, fetch round

The Pride of the Thames

.”

The boy went, and re-appeared five minutes afterwards, struggling with an antediluvian chunk of wood, that looked as though it had been recently dug out of somewhere, and dug out carelessly, so as to have been unnecessarily damaged in the process.

My own idea, on first catching sight of the object, was that it was a Roman relic of some sort, — relic of

what

I do not know, possibly of a coffin.

The neighbourhood of the upper Thames is rich in Roman relics, and my surmise seemed to me a very probable one; but our serious young man, who is a bit of a geologist, pooh-poohed my Roman relic theory, and said it was clear to the meanest intellect (in which category he seemed to be grieved that he could not conscientiously include mine) that the thing the boy had found was the fossil of a whale; and he pointed out to us various evidences proving that it must have belonged to the preglacial period.

To settle the dispute, we appealed to the boy. We told him not to be afraid, but to speak the plain truth: Was it the fossil of a pre-Adamite whale, or was it an early Roman coffin?

The boy said it was

The Pride of the Thames

.

We thought this a very humorous answer on the part of the boy at first, and somebody gave him twopence as a reward for his ready wit; but when he persisted in keeping up the joke, as we thought, too long, we got vexed with him.

“Come, come, my lad!” said our captain sharply, “don’t let us have any nonsense. You take your mother’s washing-tub home again, and bring us a boat.”

The boat-builder himself came up then, and assured us, on his word, as a practical man, that the thing really was a boat — was, in fact,

the

boat, the “double sculling skiff” selected to take us on our trip down the river.

We grumbled a good deal. We thought he might, at least, have had it whitewashed or tarred — had

something

done to it to distinguish it from a bit of a wreck; but he could not see any fault in it.

He even seemed offended at our remarks. He said he had picked us out the best boat in all his stock, and he thought we might have been more grateful.

He said it,

The Pride of the Thames

, had been in use, just as it now stood (or rather as it now hung together), for the last forty years, to

his

knowledge, and nobody had complained of it before, and he did not see why we should be the first to begin.

We argued no more.

We fastened the so-called boat together with some pieces of string, got a bit of wall-paper and pasted over the shabbier places, said our prayers, and stepped on board.

They charged us thirty-five shillings for the loan of the remnant for six days; and we could have bought the thing out-and-out for four-and-sixpence at any sale of drift-wood round the coast.

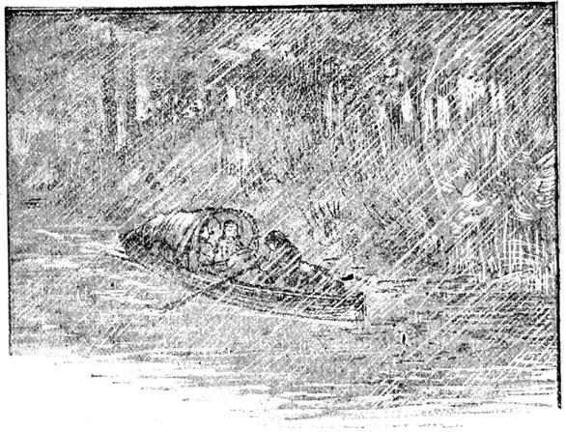

The weather changed on the third day, — Oh! I am talking about our present trip now, — and we started from Oxford upon our homeward journey in the midst of a steady drizzle.

The river — with the sunlight flashing from its dancing wavelets, gilding gold the grey-green beech-trunks, glinting through the dark, cool wood paths, chasing shadows o’er the shallows, flinging diamonds from the mill-wheels, throwing kisses to the lilies, wantoning with the weirs’ white waters, silvering moss-grown walls and bridges, brightening every tiny townlet, making sweet each lane and meadow, lying tangled in the rushes, peeping, laughing, from each inlet, gleaming gay on many a far sail, making soft the air with glory — is a golden fairy stream.

But the river — chill and weary, with the ceaseless rain-drops falling on its brown and sluggish waters, with a sound as of a woman, weeping low in some dark chamber; while the woods, all dark and silent, shrouded in their mists of vapour, stand like ghosts upon the margin; silent ghosts with eyes reproachful, like the ghosts of evil actions, like the ghosts of friends neglected — is a spirit-haunted water through the land of vain regrets.

Sunlight is the life-blood of Nature. Mother Earth looks at us with such dull, soulless eyes, when the sunlight has died away from out of her. It makes us sad to be with her then; she does not seem to know us or to care for us. She is as a widow who has lost the husband she loved, and her children touch her hand, and look up into her eyes, but gain no smile from her.

We rowed on all that day through the rain, and very melancholy work it was. We pretended, at first, that we enjoyed it. We said it was a change, and that we liked to see the river under all its different aspects. We said we could not expect to have it all sunshine, nor should we wish it. We told each other that Nature was beautiful, even in her tears.

Indeed, Harris and I were quite enthusiastic about the business, for the first few hours. And we sang a song about a gipsy’s life, and how delightful a gipsy’s existence was! — free to storm and sunshine, and to every wind that blew! — and how he enjoyed the rain, and what a lot of good it did him; and how he laughed at people who didn’t like it.

George took the fun more soberly, and stuck to the umbrella.

We hoisted the cover before we had lunch, and kept it up all the afternoon, just leaving a little space in the bow, from which one of us could paddle and keep a look-out. In this way we made nine miles, and pulled up for the night a little below Day’s Lock.

I cannot honestly say that we had a merry evening. The rain poured down with quiet persistency. Everything in the boat was damp and clammy. Supper was not a success. Cold veal pie, when you don’t feel hungry, is apt to cloy. I felt I wanted whitebait and a cutlet; Harris babbled of soles and white-sauce, and passed the remains of his pie to Montmorency, who declined it, and, apparently insulted by the offer, went and sat over at the other end of the boat by himself.