Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (5 page)

Wedding Ring: 2800

B.C

., Egypt

The origin and significance of the wedding ring is much disputed. One school of thought maintains that the modern ring is symbolic of the fetters used by barbarians to tether a bride to her captor’s home. If that be true, today’s double ring ceremonies fittingly express the newfound equality of the sexes.

The other school of thought focuses on the first actual bands exchanged in a marriage ceremony. A finger ring was first used in the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, around 2800

B.C

. To the Egyptians, a circle, having no beginning or end, signified eternity—for which marriage was binding.

Rings of gold were the most highly valued by wealthy Egyptians, and later Romans. Among numerous two-thousand-year-old rings unearthed at the site of Pompeii is one of a unique design that would become popular throughout Europe centuries later, and in America during the Flower Child era of the ’60s and ’70s. That extant gold marriage ring (of the type now called a

friendship ring

) has two carved hands clasped in a handshake.

There is evidence that young Roman men of moderate financial means often went for broke for their future brides. Tertullian, a Christian priest writing in the second century

A.D

., observed that “most women know nothing of gold except the single marriage ring placed on one finger.” In public, the average Roman housewife proudly wore her gold band, but at home, according to Tertullian, she “wore a ring of iron.”

In earlier centuries, a ring’s design often conveyed meaning. Several extant Roman bands bear a miniature key welded to one side. Not that the key sentimentally suggested a bride had unlocked her husband’s heart. Rather, in accordance with Roman law, it symbolized a central tenet of the marriage contract: that a wife was entitled to half her husband’s wealth, and that she could, at will, help herself to a bag of grain, a roll of linen, or whatever rested in his storehouse. Two millennia would drag on before that civil attitude would reemerge.

Diamond Engagement Ring: 15th Century, Venice

A Venetian wedding document dated 1503 lists “one marrying ring having diamond.” The gold wedding ring of one Mary of Modina, it was among the early betrothal rings that featured a diamond setting. They began a tradition that probably is forever.

The Venetians were the first to discover that the diamond is one of the Diamond Engagement Ring: 15th Century, Venice

hardest, most enduring substances in nature, and that fine cutting and polishing releases its brilliance. Diamonds, sets in bands of silver and gold, became popular for betrothal rings among wealthy Venetians toward the close of the fifteenth century. Rarity and cost limited their rapid proliferation throughout Europe, but their intrinsic appeal guaranteed them a future. By the seventeenth century, the diamond ring had become the most popular, sought-after statement of a European engagement.

One of history’s early diamond engagement rings was also its smallest, worn by a two-year-old bride-to-be. The ring was fashioned for the betrothal of Princess Mary, daughter of Henry VIII, to the dauphin of France, son of King Francis I. Born on February 28, 1518, the dauphin was immediately engaged as a matter of state policy, to assure a more intimate alliance between England and France. Infant Mary was presented with the veriest vogue in rings, which doubtless fit the tiny royal finger for only a short time.

Though the origin of the diamond engagement ring is known, that of betrothal rings in general is less certain. The practice began, though, well before the fifteenth century.

An early Anglo-Saxon custom required that a prospective bridegroom break some highly valued personal belonging. Half the token was kept by the groom, half by the bride’s father. A wealthy man was expected to split a piece of gold or silver. Exactly when the broken piece of metal was symbolically replaced by a ring is uncertain. The weight of historical evidence seems to indicate that betrothal rings (at least among European peoples) existed before wedding rings, and that the ring a bride received at the time of proposal was given to her again during the wedding ceremony. Etymologists find one accurate description of the engagement ring’s intent in its original Roman name,

arrhae

, meaning “earnest money.”

For Roman Catholics, the engagement ring’s official introduction is unequivocal. In

A.D

. 860, Pope Nicholas I decreed that an engagement ring become a required statement of nuptial intent. An uncompromising defender of the sanctity of marriage, Nicholas once excommunicated two archbishops who had been involved with the marriage, divorce, and remarriage of Lothair II of Lorraine, charging them with “conniving at bigamy.” For Nicholas, a ring of just any material or worth would not suffice. The engagement ring was to be of a valued metal, preferably gold, which for the husband-to-be represented a financial sacrifice; thus started a tradition.

In that century, two other customs were established: forfeiture of the ring by a man who reneged on a marriage pledge; surrender of the ring by a woman who broke off an engagement. The Church became unbending regarding the seriousness of a marriage promise and the punishment if broken. The Council of Elvira condemned the parents of a man who terminated an engagement to excommunication for three years. And if a woman backed out for reasons unacceptable to the Church, her parish priest had the authority to order her into a nunnery for life. For a time, “till death do us part” began weeks or months before a bride and groom were even united.

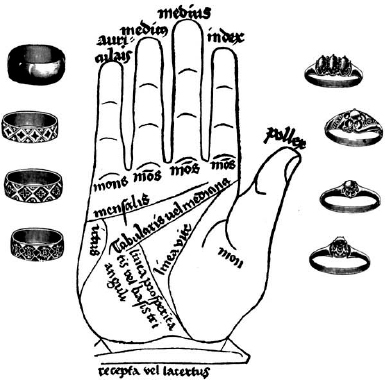

A wedding ring symbolizes the fetters used to tether a captive bride to her new home. The ring finger, adjacent to the pinky, was thought to contain a “vein of love” connecting to the heart

.

Ring Finger: 3rd Century

B.C

., Greece

The early Hebrews placed the wedding ring on the index finger. In India, nuptial rings were worn on the thumb. The Western custom of placing a wedding ring on the “third” finger (not counting the thumb) began with the Greeks, through carelessness in cataloguing human anatomy.

Greek physicians in the third century

B.C

. believed that a certain vein, the “vein of love,” ran from the “third finger” directly to the heart. It became the logical digit to carry a ring symbolizing an affair of the heart.

The Romans, plagiarizing Greek anatomy charts, adopted the ring practice unquestioningly. They did attempt to clear up the ambiguity surrounding exactly what finger constituted the third, introducing the phrase “the finger next to the least.” This also became the Roman physician’s “healing finger,” used to stir mixtures of drugs. Since the finger’s vein supposedly ran to the heart, any potentially toxic concoction would be readily recognized by a doctor “in his heart” before being administered to a patient.

The Christians continued this ring-finger practice, but worked their way across the hand to the vein of love. A groom first placed the ring on the top of the bride’s index finger, with the words “In the name of the Father.” Then, praying, “In the name of the Son,” he moved the ring to her middle finger, and finally, with the concluding words “and of the Holy Spirit, Amen,” to the third finger. This was known as the Trinitarian formula.

In the East, the Orientals did not approve of finger rings, believing them to be merely ornamental, lacking social symbolism or religious significance.

Marriage Banns: 8th Century, Europe

During European feudal times, all public announcements concerning deaths, taxes, or births were called “banns.” Today we use the term exclusively for an announcement that two people propose to marry. That interpretation began as a result of an order by Charlemagne, king of the Franks, who on Christmas Day in

A.D

. 800 was crowned Emperor of the Romans, marking the birth of the Holy Roman Empire.

Charlemagne, with a vast region to rule, had a practical medical reason for instituting marriage banns.

Among rich and poor alike, a child’s parentage was not always clear; an extramarital indiscretion could lead to a half-brother and half-sister marrying, and frequently did. Charlemagne, alarmed by the high rate of sibling marriages, and the subsequent genetic damage to the offspring, issued an edict throughout his unified kingdom: All marriages were to be publicly proclaimed at least seven days prior to the ceremony. To avoid consanguinity between the prospective bride and groom, any person with information that the man and woman were related as brother or sister, or as half-siblings, was ordered to come forth. The practice proved so successful that it was widely endorsed by all faiths.

Wedding Cake: 1st Century

B.C

., Rome

The wedding cake was not always eaten by the bride; it was originally thrown at her. It developed as one of many fertility symbols integral to the marriage ceremony. For until modern times, children were expected to follow marriage as faithfully as night follows day; and almost as frequently.

Wheat, long a symbol of fertility and prosperity, was one of the earliest grains to ceremoniously shower new brides; and unmarried young women

were expected to scramble for the grains to ensure their own betrothals, as they do today for the bridal bouquet.

Early Romans bakers, whose confectionery skills were held in higher regard than the talents of the city’s greatest builders, altered the practice. Around 100

B.C

., they began baking the wedding wheat into small, sweet cakes—to be eaten, not thrown. Wedding guests, however, loath to abandon the fun of pelting the bride with wheat confetti, often tossed the cakes.

According to the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius, author of

De rerum natura

(“On the Nature of Things”), a compromise ritual developed in which the wheat cakes were crumbled over a bride’s head. And as a further symbol of fertility, the couple was required to eat a portion of the crumbs, a custom known as

confarreatio

, or “eating together.” After exhausting the supply of cakes, guests were presented with handfuls of

confetto

— “sweet meats” —a confetti-like mixture of nuts, dried fruits, and honeyed almonds, sort of an ancient trail mix.

The practice of eating crumbs of small wedding cakes spread throughout Western Europe. In England, the crumbs were washed down with a special ale. The brew itself was referred to as

bryd ealu

, or “bride’s ale,” which evolved into the word “bridal.”

The wedding cake rite, in which tossed food symbolized an abundance of offspring, changed during lean times in the early Middle Ages. Raw wheat or rice once again showered a bride. The once-decorative cakes became simple biscuits or scones to be eaten. And guests were encouraged to bake their own biscuits and bring them to the ceremony. Leftovers were distributed among the poor. Ironically, it was these austere practices that with time, ingenuity, and French contempt for all things British led to the most opulent of wedding adornments: the multitiered cake.

The legend is this: Throughout the British Isles, it had become customary to pile the contributed scones, biscuits, and other baked goods atop one another into an enormous heap. The higher the better, for height augured prosperity for the couple, who exchanged kisses over the mound. In the 1660s, during the reign of King Charles II, a French chef (whose name, unfortunately, is lost to history) was visiting London and observed the cake-piling ceremony. Appalled at the haphazard manner in which the British stacked baked goods, often to have them tumble, he conceived the idea of transforming the mountain of bland biscuits into an iced, multitiered cake sensation. British papers of the day are supposed to have deplored the French excess, but before the close of the century, British bakers were offering the very same magnificent creations.

Throwing Shoes at the Bride: Antiquity, Asia and Europe

Today old shoes are tied to newlyweds’ cars and no one asks why. Why, of all things, shoes? And why

old

shoes?

Originally, shoes were only one of many objects tossed at a bride to wish

her a bounty of children. In fact, shoes were preferred over the equally traditional wheat and rice because from ancient times the foot was a powerful phallic symbol. In several cultures, particularly among the Eskimos, a woman experiencing difficulty in conceiving was instructed to carry a piece of an old shoe with her at all times. The preferred shoes for throwing at a bride—and later for tying to the newlyweds’ car—were old ones strictly for economic reasons. Shoes have never been inexpensive.