Lean on Pete (28 page)

Authors: Willy Vlautin

When I woke I was crying and I could hardly breathe. I lay there too scared to go back to sleep. I got up and went to my aunt’s room. Her door was half open and her bedside light was on. She was asleep with a book on her chest and her clock radio was playing. I sat down across from her and leaned against the wall. The night passed and I sat there and waited.

In the morning I woke to her shaking me.

“Charley,” she said, “are you okay?”

“I’m alright,” I said and opened my eyes.

She was dressed in her bathrobe. She had slippers on her feet.

“I get nightmares,” I said.

“They’ll get easier the more good times we have together.”

“You think so?”

“I’m pretty sure,” she said.

“I ain’t gonna be a pain in the ass,” I told her.

“Good,” she said.

“Are you going to work today?”

“I have to,” she said.

“But you’ll come back?”

“Of course I will,” she said and put out her hand. “Now come on, get up.”

Insights, Interviews & More . . .

About the author

Meet Willy Vlautin

A Conversation with Willy Vlautin

About the book

On

Lean on Pete

Read on

Have You Read? More by Willy Vlautin

Meet Willy Valutin

Willy Vlautin

is the author of

The Motel Life

,

Northline

, and

Lean on Pete

, and the singer and songwriter of the band Richmond Fontaine. He currently resides in Scappoose, Oregon.

A Conversation with Willy Vlautin

What kind of extra-literary and extra-musical jobs have you held—anything dangerous or notably mundane?

I’ve had a long series of jobs like anyone else I guess. But my first real job was at a chemical company where I loaded trucks and answered phones. After that it was mostly warehouse jobs and trucking company jobs. I did that for maybe thirteen years. I really grew to hate warehouses and even now when I drive past them I get depressed as hell. After that I became a house painter. I’d always hated house painters, and suddenly there I was one. I did it for years and eventually grew to like it all right, but Jesus, I hope I don’t have to go back anytime soon.

You somewhere expressed a fondness for John Fante and Charles Bukowski. When did you first stumble on their fiction?

I found out about John Fante later in life. A friend of mine gave me

Ask the Dust

and I plowed through it and then all his others. I think he’s a great writer. Bukowski, on the other hand, I read in college. I didn’t do much in college but hang out in the library, and I read a lot of him there. He’s one of the only things I got out of college. Crazy thing is I was young, and I had no idea about anything but I knew I liked to get drunk, and I knew I thought Bukowski was funnier than hell. I started buying all his books, and let me tell you they’re expensive and you can never find them used. So I had them lined up in my room like a shrine. At the time it was summer, and I was working for my mom. I was helping park planes during the Reno Air Races. I was hung over and sweating to death ’cause it was so hot and it was there I had this revelation: Maybe if I got rid of the Bukowski books I wouldn’t be a loser anymore. Maybe if I sold the books I wouldn’t be sweating to death and hung over. Maybe I’d have more confidence and be more normal. Maybe I’d amount to something. It had to be Bukowski’s influence that was ruining me. So I went down and sold all his books and I thought I’d straighten up and fly right, but then I had almost fifty bucks in my pocket and well. . . .

“I didn’t do much in college but hang out in the library, and I read a lot of [Bukowski] there.”

Your band, Richmond Fontaine, formed over ten years ago. But what came first, Willy the writer or Willy the rocker?

I wrote stories for myself in high school, but I never thought much of it. I wasn’t a very good student and had a hard time in English and just assumed that I wasn’t smart enough to be a writer. So I really gravitated toward music because anyone can join a band, and I loved records, records were my best friends growing up. So I started playing guitar when I was fourteen. I wrote story songs and more than anything I wanted to make a real record and have it be in a store. Have it sitting there next to all the great records of the world. So from when I was a kid up until I was thirty-five or so I just wrote novels and stories for myself. I’d just finish one and throw it in the closet and start another one.

An AllMusic.com review of your album

Miles From

, admired “the quality of Willy Vlautin’s songwriting; suggesting the clean narrative lines and morally troubling perspective of Raymond Carver, Vlautin’s tales of damaged lives and lost souls are vivid, honest, and evoke both horror and compassion in equal measures. . . .” Do you get that a lot—the Carver comparison?

I started writing seriously when I first read Raymond Carver. He changed my life. There is an Australian songwriter named Paul Kelly who wrote a song based on the Carver story “So Much Water So Close to Home.” I liked the story of the song so much I went down and found the Carver book, and I swear Carver just killed me. I was living in my girlfriend’s parents’ garage at the time, and I spent all my free time beating myself up for what a bum I was. And then I read Raymond Carver. I swear I thought I understood every line. He wasn’t better than me, he wasn’t from Harvard, he didn’t get a scholarship to Oxford, he was just a man from the Northwest trying to hang on. I was never adventurous or smart enough to be Hemingway or Steinbeck, and Bukowski lived too hard for me, but Carver was just a working-class guy with an edge that was trying to kill him. Boy, that time was something. I started writing as hard as I could from that moment on. The stories just started pouring out. I had all this sadness and darkness on my back, and I didn’t know what it was. I was just a kid. But Carver opened it all up. So yeah, I’m always grateful to get compared to him. It’s a great honor, and I’ll take it where I can get it. I know I’m just the janitor where guys like Steinbeck and William Kennedy and James Welch and Raymond Carver are the kings, but for me just trying to be a part of it is enough.

“From when I was a kid up until I was thirty-five . . . I just wrote novels and stories for myself.”

Visit

www.AuthorTracker.com

for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.

On

Lean on Pete

W

HEN

I

MOVED TO

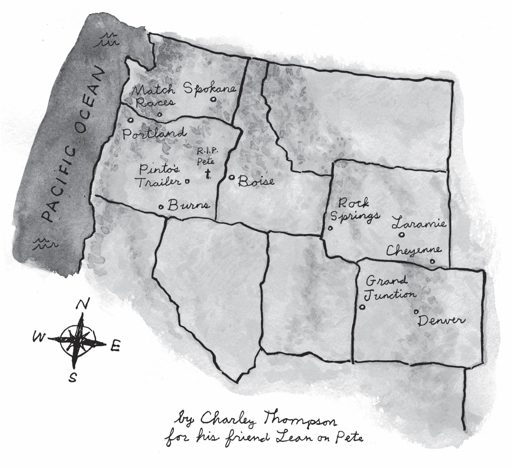

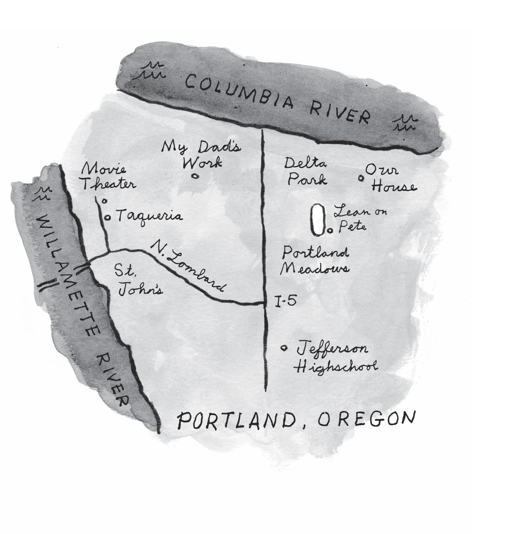

Portland, Oregon, I was twenty-six years old. I transferred up from a trucking company in Reno, and I rented a place in a suburb. I moved to Portland hoping to start a band, but I only knew one guy in town and no musicians. I was working a swing shift loading trucks with guys who’d knocked up their girlfriends and spent all their money on cars. Not one of them played music. The Portland I found wasn’t what I’d hoped it would be. I was very homesick. I wanted to move back to Reno, but, in the end, I was too proud to admit that I couldn’t make a go of it. So, instead of leaving, I began going to places that reminded me of Reno. There was an old man’s bar called Patty’s Retreat (now closed down), a great diner called Tom’s, and a local horse track Portland Meadows.

For years, it was the track that kept my heart in Portland. I’d go every chance I had. I loved the feeling that I was witnessing a once great place that is on its way out. Portland Meadows is a huge complex that can hold ten thousand people; now, it sees fewer than a thousand on a good race day. And the thousand or fewer are the gamblers, the trainers, and horse owners, people affiliated with the track. There are hardly ever tourists or young people at the races. I’ve been going since 1994, and amazingly Portland Meadows is still hanging on. Each year they say it’s the last, but they always manage to open up for one more season.

“It was the track that kept my heart in Portland.”

Within the first month of going to the track, I fell in love with everything about horse racing. I couldn’t get enough. I read novels, gambling books, and biographies about it. During Portland’s off-season, I went to other tracks, and I followed the Oregon County Fair race circuit during the summer.

When the Portland meet would start, I’d watch workouts and would try to get in on the backside, where only people affiliated with the track are allowed. I’d sit near the old-time handicappers and try to learn something from them. I began writing out there and doing my best work there. I was truly in love, and when you fall in love with something you want to learn all about it, you want to dive deeper and deeper in. But, I found out that low-level horseracing is like diving into a river with a rusted out car two feet below the surface.

“

Lean on Pete

comes from my struggle with horseracing: my love for it and my guilt for liking it so much.”

Lean on Pete

comes from my struggle with horseracing: my love for it and my guilt for liking it so much. Portland Meadows is a track at the end of its line. There’s tragedy in the horses and jockeys there. I don’t know much about the great tracks of the East Coast, and I’ve only been to Santa Anita a handful of times, so a lot of the glamour of the races is lost on me. I see the races from a more hand-to-mouth view, where horses are raced too often, where jockeys barely scrape by, and where trainers are just trying to hang on to a sport that has seen its heyday in the west.

When I first began going to the track, I didn’t realize that the horses and jockeys were disposable. I assumed the horses had decent lives and that the jockeys made a decent living for risking so much. But jockeys are independent contractors and have to hustle for rides. They don’t make much of anything unless they win. If they’re just starting out, they get stuck with the hurt, damaged, unstable, and dangerous horses—ones that can kill or at least seriously hurt a jockey. And race horses are bred for speed, and their worth is only in relation to that.

It’s taken me years to learn about the track and what goes on behind the scenes, and I’m still not much more than a novice. That’s why I wrote

Lean on Pete

the way I did, from the view of a very green fifteen year old.

A few years ago, I bought an old failed Portland Meadows race horse named A Meritable Dash. The horse in

Lean on Pete

is based on him. He’s a black quarter horse with a white star, but unlike Lean on Pete he has never won a race. My girlfriend found him living as an underweight part-time pack horse in the mountains. Now he’s spoiled and lazy and living with us.

The real Lean on Pete is a successful thoroughbred racehorse from Portland Meadows. He’s owned and trained by respected Oregon horseman David Duke. Both Lean on Pete and Mr. Duke have nothing in common with my story’s characters except the name Lean on Pete, and what a great name! It’s always been my favorite race name. I remember betting on Pete one day and telling myself that if he won I’d name the book after him, and he did win. He came in five to one. I even snuck in the winner’s photo. I was on a hot streak for a while then. I bet exactas, and they came in. Then one day I was hungover, I was eating donuts and drinking coffee and sitting on the second floor. I was going over the form when a horse I’d bet on broke its leg on the first turn. He tumbled, throwing the jockey onto the ground. The horse got up on three legs and stumbled around. The jockey lay facedown in the dirt motionless, and the race went on. After it finished an ambulance drove onto the track and the jockey was taken away, and a tractor pulling a cart came and the horse was loaded in and taken to be put down.