The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (53 page)

Read The a to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers Online

Authors: Harold Schechter

Tags: #True Crime, #General

S

PREE

K

ILLERS

In its efforts to establish precise criminal classifications, the

FBI

distinguishes between serial killing and spree killing. According to the Bureau’s definitions, a serial killer always experiences an emotional “cooling-off” period between his crimes—a hiatus lasting anywhere from days to years. By contrast, a spree killer is someone who murders a string of people in several different locations with no cooling-off period between homicides.

A classic case of spree killing occurred in 1949, when a crazed ex-GI named Howard Unruh strode through his Camden, New Jersey, neighborhood with a 9mm Luger in hand, gunning down everyone who crossed his path. In the space of just twelve minutes, he killed thirteen people and wounded three more. More recently, a twenty-seven-year-old Englishman named Michael Ryan decked himself out like Rambo—complete with an AK-47 Kalashnikov assault rifle—and spent the morning of August 19, 1987, shooting thirty people around the British market town of Hungerford.

Other spree killers, however, commit their crimes over a much more extended period of time. This can make the FBI’s distinction between spree killing and serial murder seem a little blurry. In 1984, for example, a homicidal

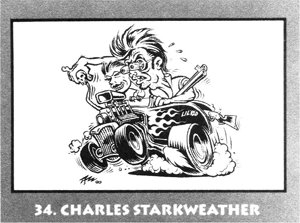

maniac named Christopher Wilder went on a murder spree that left six women dead in a month’s time. Perhaps the most famous of all American spree killers, Charles Starkweather, killed ten people during a twenty-six-day rampage through the badlands of Nebraska and Wyoming (see

Killer Couples: A Couple of Crazy Kids

).

Perhaps a more useful distinction between spree killing and serial homicide has to do with underlying motives. Serial killing is, bottom-line, a sexual crime. The serial killer spends a great deal of time (perhaps years) indulging in dark, obsessive fantasies about dominance, torture, and murder. Finally, driven by an overpowering hunger, he goes out in search of a very precise type of victim (women with long dark hair parted in the middle, for example, or Asian teenage boys). Once he has fulfilled his depraved desires, his blood lust subsides for a certain length of time, until it builds again to an irresistible need.

Charles Starkweather; from

Murderers!

trading card set

(Courtesy of Roger Worsham)

Spree killing, on the other hand, is really a form of mobile

Mass Murder

.

While the mass murderer commits his crimes in a single location (for example, the disgruntled employee who suddenly goes berserk and blows away all his co-workers), the spree killer moves from place to place (throughout a neighborhood, around a town, or even across an entire county or state). But his rampage is essentially a single extended massacre (even when it lasts for several weeks).

In short, the spree killer is generally not a sexual psychopath but a deeply unbalanced individual who suddenly snaps and embarks on a murderous

jaunt, leaving a trail of corpses in his wake. Spree killers share another trait with mass murderers: they are driven by profoundly self-destructive impulses. Typically, their rampages end with their own deaths, either by suicide or in a barrage of police gunfire. They are walking time bombs who detonate without warning, destroying everyone in sight—themselves included.

That suicidal impulse was clear in the case of Andrew Cunanan, whose cross-country rampage became a worldwide media sensation in the summer of 1997. A charismatic young man who led a glitzy, hedonistic life as the kept boy-toy of a succession of older gay males, Cunanan eventually went into a sudden downward spiral, possibly as a result of drug abuse. By the summer of 1996, the high-living party boy was leading a sordid, desperate existence. Shortly afterward, he embarked on a murderous spree that culminated in the killing of celebrated fashion designer Gianni Versace. With a mammoth manhunt under way, Cunanan took refuge in a Miami houseboat, where, on July 25, 1997, he shot himself in the head with his .40-caliber handgun.

Cunanan perfectly fit the profile of a spree killer: a profoundly embittered individual, full of suppressed rage and resentment, whose world suddenly falls apart. Life having become unendurable, he decides to go out with a bang—but not without taking others down with him. By committing such a high-profile crime, moreover, he seeks to demonstrate that he is someone to be reckoned with after all—not the nonentity he appears to be, but the kind of person who can rivet the attention of the world.

The same psychological syndrome can be seen in the case of another spree killer whose crimes held the nation in thrall: the “Beltway Sniper,” John Allen Muhammad. A supremely arrogant man, Muhammad had failed in every area of grown-up life—marriage, fatherhood, business. Seething with resentment, he blamed everyone but himself for his botched life. With the aid of a worshipful, teenaged accomplice, Muhammad—who had honed his shooting skills in the army—set off on a terrifying spree, randomly shooting more than a dozen people in the Washington, D.C., area as they went about their daily routines. As in the case of Cunanan, the crimes were Muhammad’s way both of taking revenge on society and of satisfying his own deluded sense of importance.

Unlike Cunanan, Muhammad was taken alive, though he had contrived

to end his life just the same. He awaits execution in Virginia, having been condemned to death in March 2004. His teenaged acolyte, Lee Boyd Malvo, received a life sentence.

S

TATISTICS

If you live in California and you’re the kind of person who worries obsessively about encountering a serial killer, you might consider moving to a different place—like Maine. Of all the states in the union, California has the single highest number of serial homicide cases in the twentieth century—fully 16 percent of the national total. Maine, on the other hand, has the lowest—none. Other states to avoid: New York, Texas, Illinois, and Florida. The safest places in America, at least in terms of serial murder, are Hawaii, Montana, North Dakota, Delaware, and Vermont, each of which had only one case of serial murder in of the twentieth century.

For the statistically minded student of serial murder, here are a few other interesting facts and figures:

• The United States is the hands-down leading producer of serial killers, with 76 percent of the world’s total. Europe comes in a distant second with a measly 17 percent.

• England has produced 28 percent of the European total. Germany is a very close second with 27 percent, and France is third with 13 percent.

• In terms of demographics, the vast majority of American serial killers—fully 84 percent—are Caucasian and a mere 16 percent black.

• In terms of gender, men constitute the overwhelming preponderance of serial killers—at least 90 percent. Indeed, depending on how the crime is defined, many experts believe that serial murder is an exclusively male activity. (See

Definition

and

Women

.

)

• While women constitute, at most, an infinitesimal fraction of serial murderers, they make up the majority of victims—65 percent.

• It is very rare for a serial killer to prey on members of another race. Since most serial killers are white, so are the vast majority of victims—89 percent.

• Serial murder tends to be a young person’s crime. Most serial killers—44 percent—embark on their deadly careers in their twenties, with 26 percent starting out in their teens and 24 percent in their thirties.

• If you’re seeking a career that will keep you safe from serial killers, you’ll want to avoid prostitution, since hookers are prime targets for sociopathic sex slayers. The bad news is that there really isn’t any profession that will necessarily protect you from a run-in with a serial killer. In almost 15 percent of serial-murder cases, the victims are chosen entirely at random.

S

UICIDE

See

Death Wish

.

T

HEATER

The kinds of sickos we now call serial killers—bloodthirsty butchers who revel in torture, mutilation, and every conceivable variety of murder—have been portrayed onstage for centuries. During the Elizabethan era, for example, one of the most popular forms of drama was the so-called revenge tragedy, featuring villains who were never happier than when gouging out a rival’s eyes or ripping out his entrails or feeding him pies made from the reeking flesh of his own children. Even Shakespeare got in on the act. In his play

Titus Andronicus,

a young girl—after being gang-raped—has her tongue cut out and her hands chopped off to keep her from identifying her attackers.

A few centuries later, Parisians flocked to the Theater of the Grand Guignol, which specialized in insanely sadistic skits with titles like “The Garden of Torture,” “The Merchant of Corpses,” “The Kiss of Blood,” “The Castle of Slow Death,” and “The Horrible Experiment.” The plots, such as they were, were little more than a flimsy pretext to depict the most outrageous atrocities imaginable, all simulated with shockingly realistic stage effects. Audiences shrieked, swooned, and occasionally lost their suppers as they watched

cackling psychos amputate their victims’ limbs or tear out their tongues or saw open their skulls or grill their faces on red-hot stoves.

Nowadays, the Grand Guignol tradition of gratuitous gore and stomachchurning effects has largely been taken over by low-budget slasher

Movies

(and the occasional high-end Hollywood production, like Ridley Scott’s

Hannibal).

Occasionally, however, a play about serial murder still appears on the Broadway stage. Stephen Sondheim’s 1979 “musical thriller”

Sweeney Todd,

for example, resurrects the tale of the legendary “Demon Barber of Fleet Street”—the Victorian madman who slaughtered his customers in his specially designed chair, then (with the help of his landlady-lover) turned them into meat pies. The score, one of Sondheim’s best, contains the wittiest paean to

Cannibalism

ever written (“A Little Priest”).

There are no songs in Martin McDonagh’s

The Pillowman,

which debuted on Broadway in 2005. Like Sondheim’s play, however, it contains a potent blend of horror and humor, along with some shocking moments that wouldn’t have been out of place on the stage of the Theater of the Grand Guignol. A meditation on the power of storytelling, the play deals with a series of grisly child murders that may or may not have been inspired by the macabre tales written by the main character and committed by his mentally deficient brother.

Another recent, powerfully disturbing play about serial murder is Bryony Lavery’s

Frozen,

a harrowing, three-character drama about a British woman, Nancy, whose ten-year-old daughter is abducted and slain by a serial killer; the serial killer himself, a brain-damaged pedophile named Ralph; and an American psychologist, Agnetha, who is studying the causes of serial homicide. Agnetha’s theory—that criminal psychopathology is rooted in neurological changes caused by extreme child abuse—closely echoes that of real-life criminal psychiatrist Dorothy Otnow Lewis, co-author of the influential 1999 study

Guilty by Reason of Insanity.

The similarities were not lost on Lewis, who, in 2004, launched a highly publicized plagiarism suit against the playwright, claiming that Lavery had not only ripped off her book but “stolen her life.”