The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (79 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

12.14Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

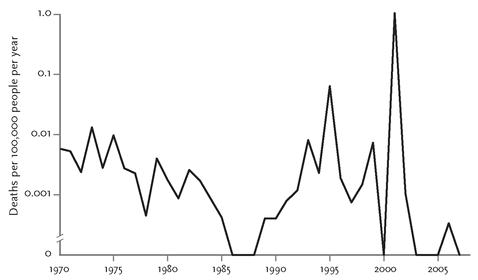

FIGURE 6–9.

Rate of deaths from terrorism, United States, 1970–2007

Rate of deaths from terrorism, United States, 1970–2007

Source:

Global Terrorism Database, START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2010,

http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

), accessed on April 6, 2010. The figure for 1993 was taken from the appendix to National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2009. Since the log of 0 is undefined, years with no deaths are plotted at the arbitrary value 0.0001.

Global Terrorism Database, START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2010,

http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

), accessed on April 6, 2010. The figure for 1993 was taken from the appendix to National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2009. Since the log of 0 is undefined, years with no deaths are plotted at the arbitrary value 0.0001.

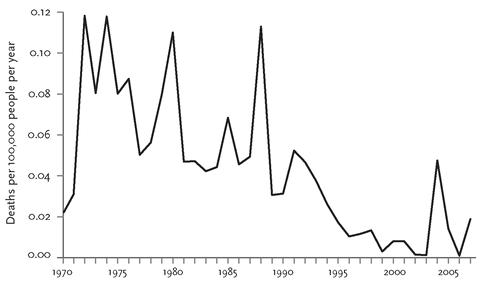

The trajectory of terrorism in Western Europe (figure 6–10) illustrates the point that most terrorist organizations fail and all of them die. Even the spike from the 2004 Madrid train bombings cannot hide the decline from the glory years of the Red Brigades and the Baader-Meinhof Gang.

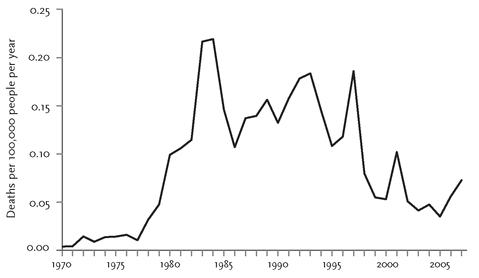

What about the world as a whole? Though Bush administration statistics released in 2007 seemed to support their warnings about a global increase in terrorism, the HSRP team noticed that their data include civilian deaths from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which would be classified as civil war casualties if they had taken place anywhere else in the world. The picture is different when the criteria are kept consistent and these deaths are excluded. Figure 6–11 shows the worldwide annual rate of death from terrorism (as usual, per 100,000 population) without these deaths. The death tolls for the world as a whole have to be interpreted with caution, because they come from a hybrid dataset and can float up and down with differences in how many news sources were consulted in each of the contributing datasets. But the shapes of the curves turn out to be the same when they include only the larger terrorist events (those with death tolls of at least twenty-five), which are so newsworthy that they are likely to have been included in all the subdatasets.

FIGURE 6–10.

Rate of deaths from terrorism, Western Europe, 1970–2007

Rate of deaths from terrorism, Western Europe, 1970–2007

Source:

Global Terrorism Database, START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2010,

http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

), accessed on April 6, 2010. Data for 1993 are interpolated. Population figures from UN

World Population Prospects

(United Nations, 2008), accessed April 23, 2010; figures for years not ending in 0 or 5 are interpolated.

Global Terrorism Database, START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2010,

http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

), accessed on April 6, 2010. Data for 1993 are interpolated. Population figures from UN

World Population Prospects

(United Nations, 2008), accessed April 23, 2010; figures for years not ending in 0 or 5 are interpolated.

FIGURE 6–11.

Rate of deaths from terrorism, worldwide, except Afghanistan 2001–and Iraq 2003–

Rate of deaths from terrorism, worldwide, except Afghanistan 2001–and Iraq 2003–

Source:

Global Terrorism Database, START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2010,

http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

), accessed on April 6, 2010. Data for 1993 are interpolated. World population figures from U.S. Census Bureau, 2010c; the population estimate for 2007 is extrapolated.

Global Terrorism Database, START (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2010,

http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/

), accessed on April 6, 2010. Data for 1993 are interpolated. World population figures from U.S. Census Bureau, 2010c; the population estimate for 2007 is extrapolated.

Like the graphs we have seen for interstate wars, civil wars, and genocides, this one has a surprise. The first decade of the new millennium—the dawn of the Age of Terror—does not show a rising curve, or a new plateau, but a decrease from peaks in the 1980s and early 1990s. Global terrorism rose in the late 1970s and declined in the 1990s for the same reasons that civil wars and genocides rose and fell during those decades. Nationalist movements sprang up in the wake of decolonization, drew support from superpowers fighting the Cold War by proxy, and died down with the fall of the Soviet empire. The bulge in the late 1970s and early 1980s is mainly the handiwork of terrorists in Latin America (El Salvador, Nicaragua, Peru, and Colombia), who were responsible for 61 percent of the deaths from terrorism between 1977 and 1984. (Many of these targets were military or police forces, which the GTD includes in its database as long as the incident was intended to gain the attention of an audience rather than to inflict direct damage.)

200

Latin America kept up its contribution in the second rise from 1985 to 1992 (about a third of the deaths), joined by the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka (15 percent) and groups in India, the Philippines, and Mozambique. Though some of the terrorist activity in India and the Philippines came from Muslim groups, only a sliver of the deaths occurred in Muslim countries: around 2 percent of them in Lebanon, and 1 percent in Pakistan. The decline of terrorism since 1997 was punctuated by peaks for 9/11 and by a recent uptick in Pakistan, mainly as a spillover from the war in Afghanistan along their nebulous border.

200

Latin America kept up its contribution in the second rise from 1985 to 1992 (about a third of the deaths), joined by the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka (15 percent) and groups in India, the Philippines, and Mozambique. Though some of the terrorist activity in India and the Philippines came from Muslim groups, only a sliver of the deaths occurred in Muslim countries: around 2 percent of them in Lebanon, and 1 percent in Pakistan. The decline of terrorism since 1997 was punctuated by peaks for 9/11 and by a recent uptick in Pakistan, mainly as a spillover from the war in Afghanistan along their nebulous border.

The numbers, then, show that we are not living in a new age of terrorism. If anything, aside from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, we are enjoying a

decline

in terrorism from decades in which it was less big a deal in our collective consciousness. Nor, until recently, has terrorism been a particularly Muslim phenomenon.

decline

in terrorism from decades in which it was less big a deal in our collective consciousness. Nor, until recently, has terrorism been a particularly Muslim phenomenon.

But isn’t it today? Shouldn’t we expect the suicide terrorists from Al Qaeda, Hamas, and Hezbollah to be picking up the slack? And what are we hiding by taking the civilian deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan, many of them victims of suicide bombers, out of the tallies? Answering these questions will require a closer look at terrorism, especially suicide terrorism, in the Islamic world.

Though 9/11 did not inaugurate a new age of terror, a case could be made that it foretold an age of Islamist suicide terror. The 9/11 hijackers could not have carried out their attacks had they not been willing to die in the process, and since then the rate of suicide attacks has soared, from fewer than 5 per year in the 1980s and 16 per year in the 1990s to 180 per year between 2001 and 2005. Most of these attacks were carried out by Islamist groups whose expressed motives were at least partly religious.

201

According to the most recent data from the National Counterterrorism Center, in 2008 Sunni Islamic extremists were responsible for almost two-thirds of the deaths from terrorism that could be attributed to a terrorist group.

202

201

According to the most recent data from the National Counterterrorism Center, in 2008 Sunni Islamic extremists were responsible for almost two-thirds of the deaths from terrorism that could be attributed to a terrorist group.

202

As a means of killing civilians, suicide terrorism is a tactic of diabolical ingenuity. It combines the ultimate in surgical weapon delivery—the precision manipulators and locomotors called hands and feet, controlled by the human eyes and brain—with the ultimate in stealth—a person who looks just like millions of other people. In technological sophistication, no battle robot comes close. The advantages are not just theoretical. Though suicide terrorism accounts for a minority of terrorist attacks, it is responsible for a majority of the casualties.

203

This bang for the buck can be irresistible to the leaders of a terrorist movement. As one Palestinian official explained, a successful mission requires only “a willing young man . . . nails, gunpowder, a light switch and a short cable, mercury (readily obtainable from thermometers), acetone.... The most expensive item is transportation to an Israeli town.”

204

The only real technological hurdle is the willingness of the young man. Ordinarily a human being is unwilling to die, the legacy of half a billion years of natural selection. How have terrorist leaders overcome this obstacle?

203

This bang for the buck can be irresistible to the leaders of a terrorist movement. As one Palestinian official explained, a successful mission requires only “a willing young man . . . nails, gunpowder, a light switch and a short cable, mercury (readily obtainable from thermometers), acetone.... The most expensive item is transportation to an Israeli town.”

204

The only real technological hurdle is the willingness of the young man. Ordinarily a human being is unwilling to die, the legacy of half a billion years of natural selection. How have terrorist leaders overcome this obstacle?

People have exposed themselves to the risk of dying in wars for as long as there have been wars, but the key term is

risk

. Natural selection works on averages, so a willingness to take a small chance of dying as part of an aggressive coalition that offers a large chance of a big fitness payoff—more land, more women, or more safety—can be favored over the course of evolution.

205

What cannot be favored is a willingness to die with certainty, which would take any genes that allow such willingness along with the dead body. It’s not surprising that suicide missions are uncommon in the history of warfare. Foraging bands prefer the safety of raids and ambushes to the hazards of set-piece battles, and even then warriors are not above claiming to have had dreams and omens that conveniently keep them out of risky encounters planned by their comrades.

206

risk

. Natural selection works on averages, so a willingness to take a small chance of dying as part of an aggressive coalition that offers a large chance of a big fitness payoff—more land, more women, or more safety—can be favored over the course of evolution.

205

What cannot be favored is a willingness to die with certainty, which would take any genes that allow such willingness along with the dead body. It’s not surprising that suicide missions are uncommon in the history of warfare. Foraging bands prefer the safety of raids and ambushes to the hazards of set-piece battles, and even then warriors are not above claiming to have had dreams and omens that conveniently keep them out of risky encounters planned by their comrades.

206

Modern armies cultivate incentives for soldiers to increase the risk they take on, such as esteem and decorations for bravery, and disincentives for them to reduce the risk, such as the shaming or punishment of cowards and the summary execution of deserters. Sometimes a special class of soldier called file closers trails behind a unit with orders to kill any soldier who fails to advance. The conflicts of interest between war leaders and foot soldiers leads to the well-known hypocrisy of military rhetoric. Here is how a British general waxed about the carnage of World War I: “Not a man shirked going through the extremely heavy barrage, or facing the machine gun and rifle fire that finally wiped them out.... I have never seen, indeed could never have imagined, such a magnificent display of gallantry, discipline, and determination.” A sergeant described it differently: “We knew it was pointless, even before we went over—crossing open ground like that. But you had to go. You were between the devil and the deep blue sea. If you go forward, you’ll likely be shot. If you go back, you’ll be court-martialed and shot. What can you do?”

207

207

Warriors may accept the risk of death in battle for another reason. The evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane, when asked whether he would lay down his life for his brother, replied, “No, but for two brothers or eight cousins.” He was invoking the phenomenon that would later be known as kin selection, inclusive fitness, and nepotistic altruism. Natural selection favors any genes that incline an organism toward making a sacrifice that helps a blood relative, as long as the benefit to the relative, discounted by the degree of relatedness, exceeds the cost to the organism. The reason is that the genes would be helping copies of

themselves

inside the bodies of those relatives and would have a long-term advantage over their narrowly selfish alternatives. Critics who are determined to misunderstand this theory imagine that it requires that organisms consciously calculate their genetic overlap with their kin and anticipate the good it will do their DNA.

208

Of course it requires only that organisms be inclined to pursue goals that help organisms that are statistically likely to be their genetic relatives. In complex organisms such as humans, this inclination is implemented as the emotion of brotherly love.

themselves

inside the bodies of those relatives and would have a long-term advantage over their narrowly selfish alternatives. Critics who are determined to misunderstand this theory imagine that it requires that organisms consciously calculate their genetic overlap with their kin and anticipate the good it will do their DNA.

208

Of course it requires only that organisms be inclined to pursue goals that help organisms that are statistically likely to be their genetic relatives. In complex organisms such as humans, this inclination is implemented as the emotion of brotherly love.

Other books

Inevitable by Angela Graham

Irish Eyes by Mary Kay Andrews

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

The Cheer in Charming an Earl (The Naughty Girls) by Locke, Emma

The Waiting Room by T. M. Wright

Dragon Rescue by Don Callander

A Tattered Love by Nickie Seidler

Black Dorn [submission/punishment/bondage] by Daryl Devore

Take Me: The Complete Series (Power Play #1-4) by Kelly Harper

In the Shadow of Gotham by Stefanie Pintoff