Read The Camel Bookmobile Online

Authors: Masha Hamilton

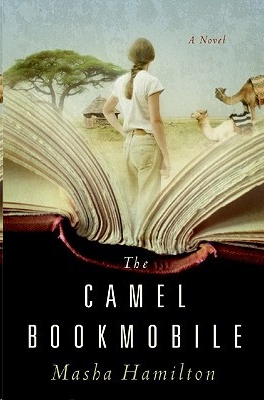

The Camel Bookmobile

The Camel Bookmobile

Masha Hamilton

For the inspiring librarians who help keep the real

Camel Bookmobile running into the African bush,

and who are dedicated to decreasing an illiteracy rate of

more than 80 percent: Rashid M. Farah,

Nimo Issack, Kaltuma Bonaya, and Joseph Otieno.

Thank you for the time my daughter and I

shared with you.

Contents

F

EBRUARY

1989—

Mididima, North-Eastern Province, Kenya

T

HE CHILD, WIDE-LEGGED ON THE GROUND, LICKED DUST

off his fist and tried to pretend he was tasting camel milk. Nearby, his father spoke to a thorny acacia while his older brother hurled rocks at a termite mound. Neither paid him any attention, but this didn’t change the fact that for the child, the three of them existed as a single entity. It was as if he drank dust, beseeched a tree, and threw stones all at once. He took this oneness for granted. Separate was a concept he was too young to recognize. Nor did he know of change, or fear, or the punishment of drought. All of life still felt predictable, and forever, and safe.

Now, for instance, this child-father-brother unit was enveloped in the reliable collapse of day, when the breeze stiffened, color drained from the sky, and shadows tinted three sets of cheeks simultaneously. The child welcomed this phase. The texture of the graying light transformed faces. It made people, he would later think, resemble charcoal portraits.

Something disturbed this particular dusk, though, tugging his attention away from the intimate comfort of his tongue on his skin and the dust’s piquant flavor. Out of the

gloom of nearby bushes rose a rigid, narrow object, standing frozen but quivering. This was odd. Everything in his experience either walked or dashed or flew or was blown by the wind or planted in the ground—in other words, it plainly moved or, less frequently, it didn’t. What could he make of this harsh immobile shuddering, this tense and stubborn suggestion of flexibility? He crawled closer, then sat back to look again.

From this perspective, he spotted another object, small and round against the other’s long narrowness. It was the color of a flame.

In fact, there were two.

Aha, he thought with satisfaction, the puzzle starting to shift into place. Eyes. Eyes, of course, moved and stayed still at once and could flicker like firelight. So the object must be human. Or maybe animal. Or maybe an ancestral ghost.

Whatever it was, he understood from somewhere, an inherited memory or intuition, that he needed all of himself to meet it. So he called to his other parts, his father-brother. “Here I am,” he said, a gentle reminder. Even as he spoke, he didn’t look away from the eyes and the rigid tail, and so he saw the object begin to grow larger. And then it lunged. It joined him, as if it too wanted to be part of the son-father-brother entity.

He was unaware of pain. Instead, the moment seemed unreal and confusing, like drifting off to sleep in the midst of one of his father’s sung tales and losing track of the story. What had already happened? What was happening still? He would have to ask his father in the morning.

Only one part remained distinct: the sound that would echo in his mind until death. The wet, high-pitched ripping of his three-year-old flesh as the spotted hyena, never a kind beast and now mad with hunger, dove onto his leg, chomped at his waist, and then reached his face and gnawed, grunting with pleasure.

Later he would hear how his father turned, killed the beast with a miraculously aimed knife, scooped his son into his arms, and began running, the child’s blood weeping down the father’s arms. He would learn that all this took less than five meditative breaths—but he would never quite believe it. In his memory, the crunching of bone and tearing of flesh stretched over a decade of sundowns and sunups, disrupting all patterns, making everything separate and fearful and dusty and fleeting forever.

M

osquitoes’ lives may be ephemeral, their deaths almost always brutal. But during their transitory span, absolutely nothing will stand in the way of their two formidable guiding desires: to soak up human lifeblood, and to reproduce.

—

A Mosquito’s Life,

J. R. Churin, 1929

D

ECEMBER

2002—

Brooklyn, New York

F

IONA

S

WEENEY SHOVED A PAIR OF ROLLED-UP JEANS INTO THE

corner of her purple duffel bag. Outside her bedroom window, a siren’s wail sliced through the white noise of a wet snowfall. Those eerie man-made moans were part of New York City’s wallpaper, a signal of trouble commonplace enough to pass unnoticed. But Fi registered this one, maybe because she knew she wouldn’t be hearing sirens for a while.

She turned her attention back to her bag, which still had space. What else should she take? Lifting a framed snapshot, she examined her mother as a young woman, wading into a stream, wearing rubber boots and carrying a fishing pole. Fi cherished the photograph; in real life, she’d never known her mother to be that carefree. The mother Fi had known wouldn’t want to go to Africa. In fact, she wouldn’t want Fi to go. Fi put the picture facedown and scanned the room, her attention drawn to a worn volume of Irish poetry by her bedside. She tucked it in.

“How about the netting?” Chris called from the living room where he sat with Devi.

“Already in,” Fi answered.

“And repellent?” asked Devi.

“Yes, yes.” Fi waved her hand as though shooing away a gnat—a gesture that Chris and Devi couldn’t see from the other room. “Should have kept my mouth shut,” she murmured.

Early on in her research about Kenya, she’d discovered that the country’s annual death toll from malaria was in the tens of thousands. She had pills; she had repellents; logically, she knew she’d be fine. Still, a figure that high jolted her. She became slightly obsessed and—here’s the rub—discussed it with Chris and Devi.

Mbu

—mosquito—had been the first Swahili word she’d learned. Sometimes the insects even dive-bombed into her nightmares. Eventually, mosquitoes became a metaphor for everything she feared about this trip: all the stories she’d read about a violent and chaotic continent, plus the jitters that come with the unknown.

And what wasn’t unknown? All she knew for sure, in fact, was why she was going. Fi’s mom had never been a big talker, but she’d been a hero, raising four kids alone. Now it was Fi’s turn to do something worthwhile.

“Fi.” Chris, at the door of the bedroom, waved in the air the paper on which he’d written a list of all the items he thought she should bring and might forget. Money belt. Hat. Granola bars. “Have you been using this?” he asked half-mockingly in the tone of a teacher.

“I hate lists,” Fi said.

He studied her a second. “OK,” he said. “Then, what do you say, take a break?”

“Yeah, c’mon, Fi. We don’t want to down all your wine

by ourselves,” Devi called from the living room, where an Enya CD played low.

Pulling back her dark, frizzy hair and securing it with a clip, Fi moved to the living room and plopped onto the floor across from Devi, who sprawled in a long skirt on the couch. Chris poured Fi a glass of cabernet and sat in the chair nearest her. If they reached out, the three of them could hold hands. Fi felt connected to them in many ways, but at the same time, she was already partly in another place and period. A soft light fell in from the window, dousing the room in a flattering glow and intensifying the sensation that everything around her was diaphanous, and that she herself was half here and half not.

“You know, there’s lots of illiteracy in

this

country,” Devi said after a moment.

“That’s why I’ve been volunteering after work,” Fi said. “But there, it’s different. They’ve never been exposed to libraries. Some have never held a book in their hands.”

“Not to mention that it’s more dangerous, which somehow makes it appealing to Fi,” Chris said to Devi, shaking his head. “Nai-robbery.”

Though he spoke lightly, his words echoed those of Fi’s brother and two sisters—especially her brother. She was ready with a retort. “I’ll mainly be in Garissa, not Nairobi,” she said. “It’s no more dangerous there than New York City. Anyway, I want to take some risks—different risks. Break out of my rut. Do something meaningful.” Then she made her tone playful. “The idealistic Irish. What can you do?”

“Sometimes idealism imposes,” Chris said. “What if all they want is food and medicine?”

“You know what I think. Books are their future. A link to the modern world.” Fi grinned. “Besides, we want

Huckleberry Finn

to arrive before

Sex in the City

reruns, don’t we?”

Devi reached out to squeeze Fi’s shoulder. “Just be home by March.”

Home. Fi glanced around, trying to consciously take in her surroundings. She’d considered subletting, which would have been the most economical decision, but she’d gotten busy and let it slide. Now she noticed that Chris had stacked her magazines neatly and stored away the candles so they wouldn’t collect dust. After she left for Kenya, Chris had told her, he’d come back to wash any glasses or plates she’d left out, make sure the post office was holding her mail, and take her plants back to his apartment. He’d thought of that, not her. A nice gesture, she kept reminding herself. Still. She gave Chris a wicked grin as she reached out to mess up the magazines on the coffee table. It felt satisfying, even though she knew he would just restack them later.