The Complete Essays (31 page)

Read The Complete Essays Online

Authors: Michel de Montaigne

Tags: #Essays, #Philosophy, #Literary Collections, #History & Surveys, #General

[A] Learned we may be with another man’s learning: we can only be wise with wisdom of our own:

[I hate a sage who is not wise for himself.]

19

[C]

‘Ex quo Ennius: Nequicquam sapere sapientem, qui ipse sibi prodesse non quiret’

[Hence what Ennius said: ‘That Sage is in no way wise who seeks not self-improvement’]…

[B] … Si

cupidus, si

Vanus et Euganea quantumvis vilior agna

[If he is avaricious and vain, or scraggier than a ewe in Euganea];

[C]

‘Non enim paranda nobis solum, sed fruenda sapientia est.’

[‘We must not only obtain Wisdom: we must enjoy her.’]

20

Dionysius used to laugh at professors of grammar who did research into the bad qualities of Ulysses yet knew nothing of their own; at musicians whose flutes were harmonious but not their morals; at orators whose studies led to talking about justice, not to being just.

21

[A] If our souls do not move with a better motion and if we do not have a healthier judgement, then I would just as soon that our pupil should spend his time playing tennis: at least his body would become more agile. But just look at him after he has spent some fifteen or sixteen years studying: nothing could be more unsuited for employment. The only improvement you can see is that his Latin and Greek have made him more conceited and more arrogant than when he left home. [C] He ought to have brought back a fuller soul: he brings back a swollen one; instead of making it weightier he has merely blown wind into it.

These

Magisters

(as Plato says of their cousins, the Sophists) are unique in promising to be the most useful of men while being the only ones who not only fail to improve what is entrusted to them (yet carpenters or masons do so) but actually make it worse. And then they charge you for it.

22

Were we to accept the terms put forward by Protagoras

23

– that either he should be paid his set fee or else his pupils should declare on oath in the temple what profit they reckoned they had gained from what he had taught them and remunerate him accordingly – these pedagogues of mine would be in for a disappointment if they had to rely on oaths based upon my experience.

[A] In my local Périgord dialect these stripling

savants

are amusingly called

Lettreferits

(‘word-struck’), as though their reading has given them, so to speak, a whack with a hammer. In truth, as often as not they appear to have been knocked below common-sense itself. Take a peasant or a cobbler: you can see them going simply and innocently about their business, talking only of what they know: whereas these fellows, who want

to rise up [C] and fight [A] armed with knowledge which is merely floating about on the surface of their brains, are for ever getting snarled up and entangled. Fine words break loose from them: but let somebody else apply them! They know their Galen but not their patient. They stuff your head full of prescriptions before they even understand what the case is about. They have learned the theory of everything: try and find one who can put it into practice.

In my own house a friend of mine had to deal with one of these fellows; he amused himself by coining some nonsensical jargon composed of disconnected phrases and borrowed passages, but often interlarded with terms bearing on their discussion: he kept the fool arguing for one whole day, thinking all the time that he was answering objections put before him. Yet he had a reputation for learning – [B] and a fine gown, too.

Vos, o patritius sanguis, quos vivere par est

Occipiti, cæco, posticœ occurrite sannœ

.

[O ye men of patrician blood! You have no eyes in the back of your heads: beware of the faces which are pulled behind your backs.]

24

[A] Whoever will look closely at persons of this sort – and they are spread about everywhere – will find as I do that for the most part they understand neither themselves nor anyone else and that while their memory is very full their judgement remains entirely hollow – unless their own nature has fashioned it for them otherwise, as I saw in the case of Adrian Turnebus who had no other profession but letters (in which he was, in my opinion, the greatest man for a millennium) yet who had nothing donnish about him except the way he wore his gown and some superficial mannerisms which might not be elegant

al Cortegiano

but which really amount to nothing.

25

[B] And I loathe people who find it harder to put up with a gown askew than with a soul askew and who judge a man by by his bow, his bearing and his boots. [A] For, within, Turnebus was the most polished of men. I often intentionally tossed him into subjects remote from his experience: his insight was so lucid, his grasp so quick and his judgement so sound that it would seem that he had never had any other business but war or statecraft.

Natures like that are fair and strong:

[B]

queis arte benigna

Et meliore luto finxit prœcordia Titan;

[Whose minds are made by Titan with gracious art and from a better clay;]

26

[A] they keep their integrity even through a bad education. Yet it is not enough that our education should not deprave us: it must change us for the better.

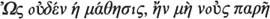

When our Courts of Parliament have to admit magistrates, some examine only their learning: others also make a practical assay of their ability by giving them a case to judge. The latter seem to me to have the better procedure, and even though both those are necessary and both needed together, nevertheless the talent for knowledge is less to be prized than that for judging. Judgement can do without knowledge: but not knowledge without judgement. It is what that Greek verse says:

–

‘what use is knowledge if there is no understanding?’

27

Would to God for the good of French justice that those Societies should prove to be as well furnished with understanding and integrity as they still are with knowledge! [C] ‘

Non vitae sed scholae discimus.’

[We are taught for the schoolroom not for life.]

28

[A] Now we are not merely to stick knowledge on to the soul: we must incorporate it into her; the soul should not be sprinkled with knowledge but steeped in it.

29

And if knowledge does not change her and make her imperfect state better then it is preferable just to leave it alone. Knowledge is a dangerous sword; in a weak hand which does not know how to wield it it gets in its master’s way and wounds him, [C]

‘ut fuerit melius non didicisse’

[so that it would have been better not to have studied at all].

30

[A] Perhaps that is why we French do not require much learning in our wives (nor does Theology) and why, when Francis Duke of Brittany, the son of John V, was exploring the possibility of a marriage to Isabella, a princess of Scotland, and was told that she had been brought up simply and

never taught to read, he replied that he liked her all the better for it and that a wife is learned enough when she can tell the difference between her husband’s undershirt and his doublet.

31

And it is not as great a wonder as they proclaim it to be that our forebears thought little of book-learning and that even now it is only found by chance in the chief councils of our monarchs; for without the unique goal which is actually set before us (that is, to get rich by means of jurisprudence, medicine, paedagogy, and Theology too, a goal which does keep such disciplines respected) you would see them still as wretched as they ever were. If they teach us neither to think well nor to act well, what have we lost? [C]

‘Postquam docti prodierunt, boni desunt.’

[Now that so many are learned, it is good men that we lack.]

32

All other knowledge is harmful in a man who has no knowledge of what is good.

But the reason that I was looking for just now, could it not also arise from the fact that since studies in France have virtually no other end than the making of money, few of those whom nature has begotten for duties noble rather than lucrative devote themselves to learning; or else they do so quite briefly, withdrawing (before having acquired a taste for learning) to a profession which has nothing in common with books; normally there are few left to devote themselves entirely to study except people with no money, who do strive to make their living from it. And the souls of people like that – souls of the basest alloy by nature, by their home upbringing and by example – bear but the false fruits of knowledge. For learning sheds no light on a soul which lacks it; it cannot make a blind man see: her task is not to furnish him with sight but to train his own and to put it through its paces – if, that is, it has legs and hoofs which are sound and capable.

Learning is a good medicine: but no medicine is powerful enough to preserve itself from taint and corruption independently of defects in the jar that it is kept in. One man sees clearly but does not see straight: consequently he sees what is good but fails to follow it; he sees knowledge and does not use it. The main statute of Plato in his

Republic

is to allocate duties to his citizens according to their natures.

33

Nature can do all, does do all: the lame are not suited to physical exercises, nor are lame souls suited to spiritual ones: misbegotten and vulgar souls are unworthy of philosophy. When we see a man ill-shod, we are not surprised when he

turns out to be a cobbler! In the same way it would seem that experience often shows us that doctors are the worst doctored, theologians the most unreformed and the learned the least able.

In Ancient times Ariston of Chios was right to say that philosophers do harm to their hearers, since most souls are incapable of profiting from such teaching, which when it cannot do good turns to bad:

‘asotos ex Aristippi: acerbos ex Zenonis schola exire.’

[debauchees come from the school of Aristippus; little savages from Zeno’s.]

34

[A] In that excellent education that Xenophon ascribed to the Persians,

35

we find that they taught their children to be virtuous, just as other peoples teach theirs to read. [C] Plato says that the eldest son in their royal succession was brought up as follows: at birth he was entrusted not to women but to eunuchs holding highest authority in the king’s entourage on account of their virtue. They accepted responsibility for making his body fair and healthy; when he was seven they instructed him in riding and hunting. When he reached fourteen they placed him into the hands of four men: the wisest man, the most just man, the most temperate man and the most valiant man in all that nation. The first taught him religion; the second, to be ever true; the third to be master of his desires; the fourth to fear nothing.

36

[A] It is a matter worthy of the highest attention that in that excellent constitution which was drawn up by Lycurgus and was truly prodigious in its perfection, the education of the children was the principal duty, yet little mention was made of instruction even in the domain of the Muses; it was as though those great-hearted youths despised any yoke save that of virtue, so that they had to be provided not with Masters of Arts but Masters of Valour, of Wisdom and of Justice – [C] an example followed by Plato in his

Laws

. [A] Their mode of teaching consisted in posing questions about the judgements and deeds of men: if the pupils condemned or praised this or that person or action, they had to justify their statement: by this means they both sharpened their understanding and learned what is right.