The Incredible Human Journey (31 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

Before flying out, I spent one more night in the village, at Marina Stepanova’s once again. And just before I left the following

morning, the other Marina, head of the reindeer herders, who had travelled back with us, sniffed both my cheeks and gave me

the reindeer boots as a gift.

The Riddle of Peking Man: Beijing, China

Having explored the genetic and archaeological evidence for the peopling of North Asia, and having experienced the deathly

chill of the taiga for myself, it was time for a change of tack, to track down the first modern human East Asians. But in

the Orient, I was going to be walking into one of the biggest controversies in palaeoanthropology, because the prevailing

theory in China is that the modern Chinese are descended from

Homo

erectus

in China. Chinese palaeoanthropologists claim that the available evidence supports regional continuity: an unbroken line of

descent from the archaic humans that made it to East Asia over a million years ago, and they even claim that the features

so characteristic of modern Chinese faces are already there in ancient Chinese

Homo erectus

fossils. This stands in direct opposition to the more widely accepted theory of a recent African origin for all anatomically

modern humans, across the globe. Social scientist Barry Sautman has argued that the Chinese state has used palaeoanthropology

in this way to support racial nationalism and foster a sense of ‘Chineseness’.

1

I left Russia, flying from Yakutsk to the severe, grey, end-of-the-world airport at Vladivostock, and on to Beijing. Once

again I was meeting two great figures from the world of palaeoanthropology: one in the present and one from the deep past.

I was to become acquainted with Professor Xingzhi Wu and Peking Man.

The argument over Peking Man and the ancestry of the Chinese people has a long history, and progress in the debate has been

stymied by a lack of open scientific communication between East and West, the language barrier further cemented by political

tensions. Anthropologists from the West have had limited access to both specimens and ideas from China.

2

But things are changing. There are now British and Canadian researchers working away on Chinese dinosaurs in the Institute

of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, and Chinese researchers are publishing more and more

in international journals.

I met Professor Wu at Zhoukoudian, the place where the Peking Man fossils had been found. It felt as if I’d come on some sort

of pilgrimage to one of the ancient places. Zhoukoudian is about 50km south-west of Beijing, in a landscape dominated by limestone

massifs riddled with fissures and caves. In 1921, a Swedish geologist called John Gunnar Andersson was visiting Zhoukoudian,

and a local resident took him to a cave that was reputed to be full of ‘dragon bones’. He realised that the bones of the mythical

creatures were in fact fossils, and, throughout the 1920s and 1930s, extensive excavations were undertaken at the site by

an international team of scientists. Ancient human teeth, and then parts of skulls, started to emerge from the ground, and

the hominin was christened

Sinanthropus pekinensis

. The fossils have since been reclassified as

Homo erectus

, and the finds from Zhoukoudian represent the largest sample of specimens of this species from a single locality.

Professor Wu led me through a tunnel-like cave into a deep, steep-sided pit on the side of Dragon-Bone Hill. I was amazed

to find out that this pit, which was around 40m in depth, had been entirely dug out as an archaeological excavation. It must

have been a mammoth undertaking. What was originally a cave in the side of the hill had filled up with sediments, and the

roof had fallen in. As the archaeologists had dug down and down, they had found layers full of limestone blocks, fossils and

stone tools. The first skull of Peking Man was found in layer 11, in sediments 20m below the surface.

The skulls of what was then called

Sinanthropus pekinensis

(literally ‘Peking China-Man’, or, as it was to become known, Peking Man) were studied by the German anatomist Franz Weidenreich,

who proposed that they represented ancestors of modern Chinese. To him, the ancient skulls possessed features that linked

them with modern populations. Weidenreich took the fragments that had been recovered in the dig at Zhoukoudian, and, with

his assistant Lucille Swan, made a reconstruction of an entire skull, which was to become the icon of the newly discovered

species.

3

The idea that Chinese people had a lineage stretching back a million years, in China, led Chinese archaeologist Lin Yan to

proclaim that the Chinese are ‘the earth’s most ancient original inhabitants’.

1

Wu and I walked up, out of the pit of Locality 1, and up on to the north-east slope of Dragon-Bone Hill, where we could look

down into the excavated Upper Cave, Shandingdong. In the 1930s, excavations in this area had yielded three well-preserved

skulls of modern humans, as well as perforated animal teeth, pebbles and shells. The Upper Cave skulls were also examined

and described by Weidenreich.

Then, in late June 1937, Chinese and Japanese troops clashed in the town of Wanping, about thirty miles from Beijing, in what

was to become known as the ‘Marco Polo Bridge Incident’, and effectively the beginning of the Second World War in the East.

By the end of July, Beijing had fallen to the Japanese. Excavations at Zhoukoudian ceased, and the precious Peking Man fossils

were packed up into crates to be sent for safe-keeping to America. But they never made it. The tragic loss of the Peking Man

fossils is one of the great mysteries of palaeoanthropology. There are all sorts of stories about where the fossils may now

reside (if indeed they still exist). Suggestions include the fossils having been removed to a museum in Taiwan, sent to the

Crimea on a Russian ship, or having been kept in a hospital in Beijing.

4

So, when I said I was to meet Peking Man, I was actually going to see casts of the original fossils.

Professor Wu and I returned to Beijing, to the IVPP, where the casts of Peking Man and the Upper Cave skulls are kept. We

entered a room where one wall was lined with lockers from floor to ceiling. A table covered in a deep red cloth stood in the

centre of the room. But then we both had to leave the room and stand in the corridor while a security officer removed the

specimens from the lockers.

‘I am not allowed to see the drawers out of which the skulls come. I will stand back and wait here.’ The location of the specimens was kept secret even from Professor Wu, such was the nature

of this magnificently elaborate security system.

‘He keeps the key so that nobody knows the number,’ said Professor Wu.

‘So you don’t know the number?’

‘No. I don’t want to know. If I know, and if it is lost, then I have the responsibility. But now I don’t know anything. I

have no responsibility,’ Wu smiled.

While we were waiting out in the corridor, I asked Professor Wu how he had become interested in palaeoanthropology. It turned

out that he had qualified as a medical doctor, but that, at the time, China had needed more medical teachers, so he was instructed

to become a lecturer in anatomy. Anatomy and palaeoanthropology have always been closely allied professions, and so when excavations

restarted at Zhoukoudian in the 1950s, Wu naturally became involved.

He asked me about my background, and I was really pleased to be able to tell him that I too had trained as a medical doctor,

then became a lecturer in anatomy, and developed an interest in palaeoanthropology. I felt like an apprentice in the presence of a grand master. At the age of eighty, Professor Wu was still coming to work every

day (on his bike) at the IVPP.

Once the specimens were out of the lockers, we could re-enter the room. Six or seven of them now sat, neatly lined up, on

the table. There were some modern human skulls, and casts of

Homo erectus

. I recognised the cast of the original Weidenreich/Swan reconstruction but I had also read about a newer reconstruction put

together by Ian Tattersall and Gary Sawyer from the American Museum of Natural History, New York, and Professor Wu had arranged

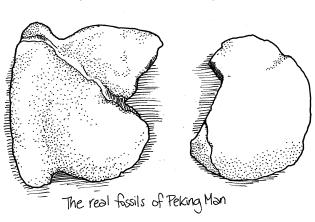

for this to be taken out as well. There were also two thick fragments from the top of a skull.

‘These are original fossils of Peking Man,’ he said. I was taken aback. I knew the story of the missing crates of fossils in the Second World War, and I had not expected to see any

actual

fossils, just casts.

‘I honestly thought all the specimens had been lost,’ I said.

‘After the war, in the 1950s, we carried out some new excavations, and we got some new specimens,’ explained Wu.

So I was holding in my hands fragments of a skull of an earlier human who had lived in China some one million years ago. It

was quite a strange moment: there was something about the physicality of holding something I knew to be truly ancient. The

vast depths of time through which these fossilised bones had passed, and then to end up in the present as some sort of magical

talisman that could give us the power to know the past, made me feel almost giddy. A great range of dating techniques has

been used to pin down the dates of the layers at Zhoukoudian. Most suggest that the hominin fossils come from layers dating

to between 400,000 and 250,000 years ago. But the latest uranium series dates suggest that the fossils may be more than 400,000

years old, and perhaps as much as 800,000 years.

5

,

6

I laid the fragments back down on the red cloth. This was Chinese

erectus

, the real thing, with its massive brow and sloping forehead.

Having got over the shock of seeing Peking Man, I turned my attention to the reconstructed casts – and the face of Chinese

Homo

erectus

. The Weidenreich/Swan and Tattersall/Sawyer reconstructions were quite different looking. Professor Ian Tattersall had

wanted to make a new reconstruction using more fragments from the face than had been used in the Weidenreich model. This had

been possible, because, although the majority of original fossil fragments had been lost, casts had survived – and there were

fragments of twelve separate skulls to work from. The original reconstruction had been based on just three pieces of skull:

the skullcap, part of the right side of the mandible and a fragment of the left maxilla (the bone that bears the upper teeth

and forms much of the cheek), and photographs and casts of this reconstruction didn’t make it obvious which parts were real

and which were ‘restored’. Tattersall and Sawyer had wanted to keep artistic licence to a minimum, by using as many fragments of facial bones as possible in their

reconstruction.

3

Professor Wu held up the Weidenreich/ Swan reconstruction and started to point out the features that he thought to be evidence

for regional continuity. He indicated the flatness of the bridge of the nose, and the shape of the edges of the cheekbones. Then he pointed to these features on his own face and mine: it was true that he had a much less pronounced bridge of the nose

than I had, and much wider, flatter cheekbones. But I couldn’t really see any similarity between Professor Wu’s face and that

of Peking Man, even though it seemed that the Weidenreich/Swan reconstruction had somehow accentuated these Chinese-looking

features. On the Tattersall/Sawyer skull, the nasal bones were more prominent, the face taller and narrower across the cheekbones,

and the jaw more protruding. In general, this reconstruction looked less ‘Chinese’ and more like other

erectus

specimens around the world.

3

The shape of the front teeth was another feature that Wu considered as evidence of regional continuity. Weidenreich had proposed

that shovel-shaped incisors were a regional trait shared by Chinese

Homo erectus

and many modern Chinese. But this tooth shape is also seen in African

erectus

and in Neanderthals, so, while it may be an archaic trait, it is not specifically East Asian. And the shovel shape seen in

the teeth of some living Chinese people seems to be developmentally different from the shovelling of the archaic teeth, even

though it looks superficially similar – in which case it can’t be used to argue for a connection at all.

7