The Training Ground (28 page)

Despite that remarkable achievement, the Mexican people were unbowed — and unimpressed. “The Americans should not even speak of the bombardment of Veracruz. The walls of Veracruz are in no way strong or impregnable,” one Mexican journalist wrote. “More than 500 innocent children, women, and old people perished under the enemy cannonade, and the valiant garrison under General Morales had to submit to a capitulation, because the entire city would have been ruined and all the innocents sacrificed to no avail.”

The writer concluded with a disgusted nod to the changing face of warfare: “A military action which relied solely on the superiority of the missiles should not even be mentioned.”

Scott soon assembled a list of men to be commended for their “noble services” during the battle. Lee was on it. Colonel Totten, his direct superior, was soon dispatched to Washington to deliver news of the victory. When Major John L. Smith, the senior man, then became ill, Lee was instantly elevated to a position as Scott’s senior engineer.

M

EADE, ON THE

other hand, was all but forgotten. As the navy spent its days off-loading munitions and supplies, and the army steeled itself for the dramatic march to Mexico City, the topographer had been ordered home. “I found myself at Veracruz a perfect cipher; the major, three captains, and one lieutenant I had over my head depriving me of any opportunity I might otherwise have of distinction,” he groused in a letter to Margaretta. Meade was known to be deeply fond of Zachary Taylor and was something of a rogue among the topogs in Veracruz, owing to the fact the orders had not yet been cut reassigning him to Scott’s command. He had fallen into a military limbo, still technically under Taylor’s authority while physically in Scott’s theater of war. Meade had complained about his inactivity to General Worth, who in turn demanded an explanation from Major William Turnbull, the ranking topographer. Turnbull shrugged, saying that he had more than enough topographers to do the limited jobs to which his unit had been assigned.

Before Scott sent him back to Washington, Colonel Totten had seen to it that the prime assignments fell to men under his command and not to the Topographical Corps. Now, the duties of mapping and forward reconnaissance that Meade had done so well since Matamoros were being turned over to men like Lee. Meade groused that Totten “wishes to make as much capital for his own corps, and give us as little as possible.”

In the midst of a monumental invasion, with a rugged and potentially bloody stretch of road between the American army and Mexico City, and at a time when experienced cartographers would be vital to analyzing the lay of the land, Meade was being told that there was nothing for him to do.

He was ordered home. Meade was not happy about the transfer. There was the slightest whiff of failure to his homecoming, for so few other officers were leaving the front. “What will you say to my return?” he wrote his wife. “And what will your dear father say? I will frankly acknowledge that I had a most anxious time in making up my mind what to do. I, however, reasoned, that it was my intention, from the first moment I left you, to perform my duty and remain so long as duty required me, but to retire whenever I could do so honorably, and could not retire in a more honorable manner than I have done.”

Meade’s departure was swift, even if his journey home was not. He boarded the steamship

Alabama

on March 31, stopped two days in Tampico and a third on Brazos Island, and then endured another twenty-four hours stuck on a sandbar at the mouth of the Mississippi. His ten-day trip to New Orleans should have ended six days earlier, but the duration gave Meade plenty of time to reflect. Although there was little chance that he would see combat again, this did not sadden him. Meade knew that there would be no more significant warfare in northern Mexico (insurgents and bandits had taken to harassing American supply columns and lone American soldiers) and was afraid that his commanding officer would reassign him to Monterrey, where the work would be administrative. And he was also afraid of being posted somewhere out on the Great Plains, surveying wagon trails in the middle of nowhere. The postwar promotions would go to the warriors, and the personal connections that arose from being part of a large army on the move would benefit those soldiers even more.

Meade knew that, and he struggled to find a silver lining to the cloud that had just thrown a shadow over his career. It was not a cloud of shame, for he had performed his job admirably and with courage. Rather, it was a cloud of bad fortune, sending him back to the safety of Washington at a time when the men of West Point were finally getting the chance to be soldiers.

Meade set those thoughts aside and allowed himself to dream of being home. And when he did, Meade was eager to be with his wife and children after more than a year’s absence. “Rest assured,” he wrote Margaretta from New Orleans, “I shall leave no exertion unspared to hasten the moment when I shall hold you and my ever dear children in my arms.”

National Road

A

PRIL 8, 1847

T

he weather was blazing hot, tempered ever so slightly by a fresh sea breeze. Just a little more than a week after the fall of Veracruz, Scott had ordered General David Twiggs to march his division on to Mexico City. Their first stop would be Jalapa, seventy-four miles inland, at an altitude of 4,680 feet. From a military standpoint, the march presented major obstacles in the form of a river crossing (the Río Antigua) and mountain passes at Plan del Río, Cerro Gordo, and Corral Falso. Each of these presented a potential bottleneck of American troops and offered the Mexicans prime opportunities to thwart the invasion.

Thomas Jackson was among the twenty-six hundred men and two batteries of flying artillery setting out from Veracruz. An advance screen of dragoons rode before them to suss out the terrain. They were an army in a hurry, and each man was stripped down to the essentials of uniform, canteen, bedroll, and weapons. Extra baggage was forbidden, and each company was limited to three tents, to be used only for the sick or the wounded and for the protection of weapons in case of rain.

Though ravaged by the bombardment, in some ways occupied Veracruz had been lovely, and after their bland shipboard diet the men had exulted in delicacies like oysters, fresh tomatoes, eggs, and lemonade. But the soldiers were glad to be away. Yellow fever had a gestation period of just three to five days, and already many men were getting sick, thanks to their weeks of exposure to the elements — and to the mosquitoes in particular. They drank little alcohol for fear of weakening their immune systems and falling prey to

el vómito

or to the diarrhea they had come to know all too well back on the Rio Grande. Each soldier, even the hardheaded volunteers, had begun to treat disease with the same cautious fear as they would the enemy. But for some it was too late, and American corpses began to pile up. (Some 1,721 Americans would have been killed in combat and 4,102 wounded when the war in Mexico finally came to an end, but an astonishing 11,562 would have succumbed to disease or accidents.)

Contrarily, Jackson, the quiet hypochondriac, was feeling not only well but better than he had in a very long time. “I probably look better than I have in years,” he wrote to his sister.

Jackson had been busy during the siege. There had been no time for advanced artillery training after his West Point graduation, but he had been more than adequately educated on the sands of Veracruz. Jackson’s battery was on the front lines, his commanding officer John Bankhead Magruder. “Prince John,” who had built the theater at Corpus Christi and fought at Resaca de la Palma before being reassigned to the recruiting service for several months, had been promoted to captain in June. His gregarious personality, imposing physical size, pronounced lisp, and determination to be in the thick of every battle made Magruder a flamboyant and deeply charismatic leader. He was also a strict disciplinarian, which made him an ideal commander for Jackson, whose zeal for rules and restraint bordered on the fanatical.

For Jackson there had been great satisfaction in the destruction of Veracruz, which he saw as a necessary step toward defeating Mexico. He had not been shaken in the least when an enemy cannonball missed him by just a few feet, and he was more than content to deflect glory onto the artillery commanders who had already plied their craft with steady brilliance under Taylor’s command. “That portion of praise which may be due to me must of course go to those above me or be included in the praise given to the army,” he wrote Laura.

The aftermath brought out yet another side of Jackson’s very complicated personality. He was known by many for the twang of his backwoods Virginia accent, and by his West Point brethren for his determination to succeed at all costs. But there was also an outspoken side to Thomas Jackson, one that few soldiers ever saw, for he preserved his sharpest comments for his letters home. “This capitulation has thrown into our hands the strong hold of this republic and being a regular [siege] in connection with other circumstances must in my opinion excel any military operations known in the history of our country,” he wrote Laura. Jackson could not and would not understand the logic of releasing enemy prisoners. “I approve of all except allowing the enemy to retire that I can not approve of in as much as we had them secure and could have taken them prisoners of war unconditionally.”

What might have been seen as a cold heart was, in fact, canniness. Rumors were flying that General Santa Anna was racing back from Buena Vista with the remainder of his army to confront Scott. The Mexican soldiers from Veracruz were sure to flee westward toward their military brethren, where they would be rearmed and sent straight back into battle. Jackson realized that in the long run, keeping prisoners now would save lives later.

The rumors were true: Santa Anna had marched straight from Buena Vista to Mexico City, seized control of the Mexican government in order to quell the growing dissent at his performance in the field, and then on April 2 hurried his troops east toward Jalapa, which was not only the American’s intermediate destination, but also the location of Santa Anna’s personal hacienda.

Santa Anna arrived in Jalapa on April 5, and after a two-day reconnaissance, he chose the mountain pass at Cerro Gordo, as the site where his army would position themselves and throw the Americans back into the sea.

Now, a day later, Jackson marched toward this showdown. He had been with Worth’s division during the siege, stationed on the southern end of the American line. But Worth would linger a few days more to serve as temporary military governor of Veracruz. Elements of his division were being divided between other generals. Now Jackson was commanded by Twiggs, the towering and somewhat dim-witted Georgian with the prebattle bowel superstitions.

Jackson’s performance at Veracruz had resulted in a promotion to full second lieutenant. He was eager to continue his upward advance by making a name for himself in another battle. But the National Road was a twisting route, and if battle came, it was hard to imagine that artillery would be as effective as infantry, for its mobility would be minimal when the passage turned mountainous. Many of the men were making the situation more precarious by falling behind during the march, thanks to the heat and an overall lack of fitness, making them a perfect target.

Jackson and his gun crews were not among the stragglers. They slogged slowly away from the beach. The trail was lined with palm trees and resplendent with exotic flowers and vegetation, but it was also thick with sand until the army finally linked up with the National Road. The Spaniards under Cortés had leveled the road and covered it in pavers three centuries earlier, making it the ideal path for yet another invading army. With his left arm raised high to enhance his circulation, Jackson slowly rode forward into the mountains.

Twiggs’s Dilemma

A

PRIL 15, 1847

J

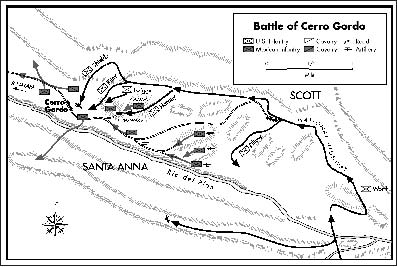

ust outside the village of Cerro Gordo, the National Road passed through a long valley. Steep cliffs and sudden drop-offs defined the wooded terrain. Mexican gun batteries had been placed atop hills on either side of the road, and troops were stationed at the mouth of the ravine. Should Twiggs have made it past the Mexican cannons, his outnumbered army would be penned inside the valley as Mexican forces swarmed over them. Santa Anna had selected an invincible position.

Twiggs was a confrontational sort. A head-on attack suited his personality. Tactically, it wasn’t the prettiest way to get at Santa Anna, but on a practical level, there was no other way to get an army from one side of the pass to the other. Twiggs knew it. Santa Anna knew it. As bloody as it would be, Twiggs’s suicidal charge made perfect logistical sense.

On April 12, Twiggs probed the pass with an advance unit led by William Hardee, which immediately came under fire and withdrew. Determined to test the Mexican defenses again, this time under cover of darkness, Twiggs decided to invade the pass at 4:00 a.m. on the thirteenth. The plan fell through when units led by Generals Gideon Pillow and James Shields, a pair of young volunteer Democrats (forty and thirty-six, respectively) appointed to their ranks by President Polk, arrived shortly before the attack was to begin. The volunteers were too tired to be effective, claimed the generals. Twiggs was reluctantly forced to postpone his charge for twenty-four hours.

The mood in the camp turned somber as the hours counted down, and the soldiers dreaded the coming morning. They knew that few of them would survive the attack. Wrote one soldier, “On the night before the expected engagement the camp wore an air of stillness unusual at other times, the men generally appearing more thoughtful, and conversing less, and in more subdued tones than usual. On the evening of the 13th, General Twiggs, who, during the sickness of General Patterson, commanded the forces at Plan del Río, after having spent two days in reconnoitering, gave the order for an attack on the enemy’s batteries, which we were to take at the point of the bayonet by assault, early next morning. The bugle having sounded for the troops to assemble a little before sunset, the captains of companies addressed their men, informing them of the General’s intention, and explaining as much of the plan of the meditated attack as would tend to facilitate its execution. They concluded with a hope that all would do their duty gallantly, and required us to give three cheers, an invitation which was very faintly responded to. The want of enthusiasm displayed by the men, arose, I am persuaded, from a want of confidence in the judgment of General Twiggs, and not from any deficiency of the necessary pluck required for the occasion. But that General, though always admitted to be a brave old cavalry officer, was considered, from his peculiar temperament, and previous school of education and discipline, to be totally incapable of successfully directing an operation of such magnitude as the present, which any person might easily see required both military talent and skill.”

Of all people, it was General Patterson who saved the day. The political appointee, who outranked Twiggs, rose from his sickbed and took command, calling off the attack. The American army would hold its present position and wait for Scott to tell them how best to move forward up the valley. This rare example of a volunteer general’s making a sound decision saved countless American lives.

Dana, still on the road to Cerro Gordo, could hear the distant sounds of artillery as Mexican guns took aim on the American positions. Dana had recently been promoted to first lieutenant and was in command of a company, marching inland with the Fourth Infantry. All he knew of the action were rumors that Santa Anna’s twelve-thousand-man army had been located at Cerro Gordo, and that Twiggs had nearly attempted a premature head-on assault of the position. Those rumors sent shivers through the American army, who knew all too well that their inferior numbers would likely spell doom in waging such a battle against a fortified position. “General Twiggs intended to attack,” Dana wrote. “But I rather think that General Scott got up in time to stop him until he gets ready. He will probably wait for us to come up, and then he will put Santa Anna in a mighty bad fix.” Dana hadn’t played an active part in a battle since Monterrey and was eager to get back into action.

“It may be that the fight will be over before we reach there,” he wrote to Sue. “I have no doubt that there are a good many in Santa Anna’s army who surrendered and were paroled at Veracruz. If so, and we can get hold of any of them and detect them, they will be shot to a certainty.”

Dana’s bold predictions had been correct throughout the war, but Cerro Gordo would be a different story. Dana’s luck in battle would finally run out.