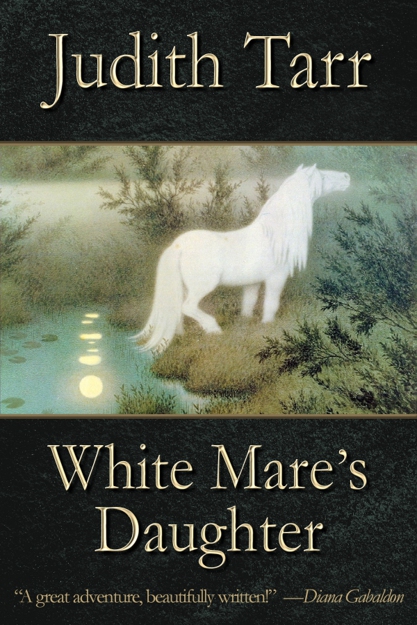

Read White Mare's Daughter Online

Authors: Judith Tarr

Tags: #prehistorical, #Old Europe, #feminist fiction, #horses

White Mare's Daughter

WHITE MARE’S DAUGHTER

The Epona Sequence, Book 1

Judith Tarr

Book View Café Publishing Cooperative

January 28, 2014

ISBN: 978-1-61138-356-0

Copyright © 1998 Judith Tarr

This book could not have been written without the help, advice,

suggestions, and plain old aid-and-comfort of the following:

Professor David W. Anthony of the Institute for Ancient

Equestrian Studies, whose work on the very early history of riding was the

original impetus for this book, and who suggested a time and place in which it

might be set;

Joanne Bertin and Sam Gailey, who trekked through a blizzard to

hear and record a lecture that was critical to the background of the book;

Beth Meacham, who asked for it and, I hope, got it;

Jane Butler and Danny Baror, who leaned on me till it was done;

Russ Galen, who picked it up and carried it on;

the members of the Internet mailing lists Equine-L and

Dressage-L, for daily, hands-on assistance and research;

the Internet “coven” who held my hand during the final throes;

and of course the three White Ladies and the famous Keed, and

all the rest of the horses who provided the original and ongoing inspiration

for the book.

I: HORSE GODDESS’ SERVANT

1

From far away she heard them, echoing across the steppe:

the drums beating, swift as a frightened heart. The voices were too far, too

thin to carry above the shrilling of the wind, and yet in her belly she knew

them, deep voices and high, strong and wild.

Blood and fire! Blood

and fire! Fire and water and stone and blood!

They had made the year-sacrifice, one of many that they

would make in the gathering of the tribes. On this day, from the rhythm of the

drums, it would be the Bull. Yesterday, the Hound; tomorrow, the Stallion, with

his proud neck red like blood.

She laid a hand on the Mare’s neck. In the rolling of years

it would be white, like milk. Now it was the grey of the rain that had fallen

in the morning, shot with dapples like flecks of snow. The Mare snorted lightly

and tossed her head. She could smell the stallions. It was her season, the

strong one that waxed with the moon in spring, and would wax and wane slowly

with each moon all the summer long, and in winter sleep.

She snorted again and pawed, impatient to be going. Her

rider eased a little on the broad grey back, freeing her to spring forward. The

wind tangled in thick grey mane and silver tail; caught the long thick braid

that hung to the rider’s buttocks and sent it streaming out behind. The

pounding of hooves blotted out the drumbeats. They raced the wind then, swift

over the new grass, into the westering sun.

oOo

The gathering of the people spread wide in a hollow of the

steppe, where a river ran through a cutting that deepened with the years.

Winter’s storms brought down the banks nonetheless, and the herds of horses and

cattle made broad paths to the water.

The herds were the girdle that bound the camp. The center,

the soft body, divided into circles of camps, each with the staff and banner of

its tribe: black horsetail, red horsetail, spotted bull’s hide, white bull’s

horns, and three whole handfuls of others; and in the center, in the

king-place, the white mare’s tail catching the strong wind of spring.

Agni was on his way to the king’s circle, but taking his

time about it. The dancing, that had begun where the hill of sacrifice rose

dark with blood, had wound away toward the river. He had been part of it when

it began, before the king’s summons brought him back in toward the white

horsetail. His father was entertaining the chiefs of tribe and clan in the

feast of the Bull, and had called on Agni to stand at his right hand. Rumor had

it among the tribes that the old man was going to name an heir at last; and he

had called for Agni, the avowed favorite of all his sons.

Agni was sensible of the honor, and of what it meant—how

could he not be? But he dearly loved the dance, and the delights that came with

it. He was none too eager to forsake it for the dull dignity of the elders in

their circle.

As he made his somewhat desultory way past the tents in the

center, a hiss brought him about. Someone had lifted the back of a tent. A

white hand beckoned from beneath, and a slender arm heavy with ornaments: carved

bone and stone, beads strung on leather, and one woven of horsehair that he

knew very well.

His breath quickened. Completely without thinking, he

dropped down and slithered into the tent.

It was black dark to his day-accustomed eyes, heavy with

scents of musk and sweat and tanned hides. Strong slender arms circled his

neck. A supple body pressed against his. Warm lips fastened on his own. They

fell in a dizzy whirl.

She was as naked as she was born, slick with sweat, white

glimmering body coming clear in the gloom; and her hair, her wonderful hair,

like a pale fall of sunlight. He could drown himself in the stream of it.

For the dance one wore nothing but a kilt of fine-tanned

leather—very fine, if one were a prince. It was no barrier to a woman’s

urgency, least of all if it were this one. She did not even wait for him to

shed it. She flicked it up and opened her thighs and took him where they lay

entangled. She was burning hot, as hill of the god as any man, and imperious in

her urgency.

He had brought with him the heat of the dance. The Bull was

in him, driving deep. She gasped; then laughed. “Again! O beautiful! Again!”

He was the Bull, the god’s own. He heeded no woman’s

bidding. But the god in her—that one he was glad to obey. He took her as the

bull takes the heifer, but with a man’s strength, and a man’s endurance, too,

riding her till her breath shuddered and a cry burst out of her—muted swiftly,

but sharp enough for all of that.

He let it go then, with a gasp but no cry; for he was more

circumspect than she. She locked arms and legs about him, took him as deep as

ever she could, draining him of every drop of seed.

When he was all empty, she let him go. He rolled on his

back, gulping air, quivering still.

She lifted herself over him, white breasts swaying. They

were the color of milk, the nipples pale, like the sky at morning. She teased

him with them, tormenting him, brushing his face and his sweating breast,

knowing full well that he had no strength left to rouse. “O beautiful,” she

said. “O prince. Be like a god. Love me again.”

He looked past her breasts to her laughing, mocking face.

She was beautiful in everything, with her white skin and her delicate bones and

her eyes the color of a winter sky. She could drive a man mad. Indeed she often

had.

His eye followed the line of her shoulder to her arm, and

down it to the wrist, to the one ornament of them all that mattered: the

bracelet woven from the hair of a white mare and a red stallion, woven on her

living arm, intricate and strong, to last lifelong. “The god is gone from me,”

he said, “and the king is waiting.”

“Ah,” she said without contrition. “Have you kept him

standing about? For shame!”

“Sitting,” said Agni, “in his circle as he always is, with

my brothers on the edges, vying to catch his eye.”

“But only you ever truly catch it,” she said.

“You should have married me, then,” said Agni, “and not my

brother Yama.”

Her face twisted delightfully, a moue of disgust. “That was

my idiot of a father, insisting on giving me to the eldest, and not the one who

would be king. I would have waited, and made him ask the king for you, once you

were a man. I want to be a king’s wife.”

“You should be a king’s wife,” Agni said with sudden

fierceness, seizing her and holding her tight. She laughed, fearless. Her hips

rocked against him. He was reviving; but not enough to matter. Not yet. “When

I’m king, I’ll make my brother give you up.”

“Oh, no,” she said. “That would only be dishonor. I’d have

to go back to my father; and I could never be the king’s wife then. You’ll have

to kill your brother, my prince. Then I can be your wife.”

Agni’s stomach clenched round a small cold knot. But he

managed to laugh. “Oh, you are a fierce creature! Come, give me a kiss, and let

me go. I have to stand beside the king.”

“Oh yes,” she said sulkily. “Leave me for that smelly old

man. And make me lie here waiting for my so-noble husband to remember that I

exist.”

“I don’t see how he can forget,” Agni said. Her kiss nearly

broke his resolve; and her breasts rising as her back arched; and the hot moist

valley of her sex, coaxing him to lose himself in it.

But the king was waiting, and Agni had dallied more than

long enough. He slipped out the way he had come, biting back the smile that

kept breaking out in spite of him. If he came flushed and disheveled to the

king—well, and the dance was wild, and he had come straight from it. Had he

not?

He glanced back once, half expecting to see her peering

through the gap in the tent’s wall. But the gap had vanished. She nursed her

sulks in solitude.

oOo

If the king had grown impatient, he did not show it. Agni

presented himself in the circle of elders, bowed as was proper, and received

the gesture that he had looked for: bidding him come in, even to the center,

and wait on his father. His brothers were where Agni had known they would be,

relegated to places unhappily distant, except for the lighthearted few who had

gone off with the dancers.

Yama in particular glared poison at him. Yama was the

eldest, though begotten of a mere prince and not a ruling king, and fancied

himself greatly; but he was never the hunter or the fighter that Agni was, and

everyone but Yama knew it. No more did he know what was between Agni and the

youngest and fairest of his three wives. That was a secret that Agni meant to

keep—for Rudira’s sake if not for his own. She could die for what she did.

Agni liked to think that what they had was in some way

blessed, though the priests would have been appalled to hear it. Was he not the

king’s heir? Was she not the fairest woman in the tribes?

He would have been glad to be with her now, or with the

dancers who had reached the river and begun the circle back. He could not help

a longing glance or six toward the leaping, yelling skein of men and boys. They

would dance round and round and inabout, weaving together every strand of the

camp, till it was all bound up and blessed of the Bull; and then they would

drink the strong dizzying kumiss till the moon went down, and fall insensible

on the ground, and so bless that. Agni was not so enamored of the headache

afterward, but he did love the dance and the drinking, the laughter and

singing, and maybe, if one was lucky, a willing girl creeping out of a tent to

lie, as they said, with the Bull—meaning any young man full of drink and the

god.

Not, thought Agni, that he had failed to give the gods their

due. Maybe Rudira would quicken from this night—and maybe Yama would claim the

son that came of it, but Agni would know, and she would know, whose it truly

was.

He sighed and did his best not to look bored. The elders and

the chieftains had little to say. Their mouths were too full of the Bull, their

faces slick with grease. Their cups were kept well filled with kumiss that he

as servant was not permitted, and for the few who held to the oldest ways, the

Bull’s own blood caught fresh from the cutting of his throat.

“You! Boy!”

Agni started to attention. The old man glowered up at

him—his wonted expression, and no more eloquent of disapproval than it ever

was. “You, boy,” he said in a somewhat milder tone. “Go on, go and play, I’ll

share a cupbearer with old Muti here.”

Old Muti was, as far as anyone knew, some considerable

number of seasons younger than his king; but it was true, he did look older,

with his toothless grin and rheumy eyes. The man who waited on him had the same

face, albeit much younger—and already gaptoothed when he grinned at Agni.