Read Glacier National Park Online

Authors: Mike Graf

Glacier National Park (5 page)

A cascade of small boulders and rocks showered

onto the glacier from the cliffs above. Then a large chunk of ice broke away and tumbled into the lake.

The newly formed iceberg dipped below the water and bobbed and weaved its way to the surface. A series of rippling waves followed, flowing toward the shore.

Slowly, the free-floating chunk of ice steadied. Rick turned toward the group, grinning. “Well, you don’t get to see that every day!”

Once everything appeared stable, Rick presented more information. “We used to lead our hikes onto the glacier itself. Obviously that can’t be done anymore because of the lake. Come here, everyone, I want to show you some pictures.”

The group gathered around while Rick held up a poster. “This is the park’s Boulder Glacier in the 1930s.” Rick’s picture showed the tongue of the glacier with a large ice cave in it.

“And here it is now.” The next photo showed the same area, completely barren of ice and snow.

Rick held up another picture. “Here’s Grinnell Glacier years ago. Notice how it was attached all the way up to Salamander Glacier.”

“Wow,” a person in the group exclaimed. “It really has lost a lot of snow.”

Someone in the group raised her hand. “What makes it a glacier and not a snowfield?”

“Excellent question,” Rick replied. “A snowfield is formed by more snow accumulating than melting. If the snowfield continues to grow each year, it eventually gets large enough to move. That’s when we call it a glacier. Usually they have to be 90 to 100 feet thick to start moving. When glaciers lose ice mass and stop moving, they are no longer glaciers.

“I’d like to have a couple of young, strong volunteers for a demonstration,” Rick said next.

The group looked at Morgan and James, the only children on the walk. “Perfect!” Rick said, following the group’s eyes. “Would you two mind helping me out?”

Morgan and James stepped up. Rick handed each of them two small stones. He kept a pair for himself. “What I’d like you to do,” Rick explained, “is take the sharp edge of one rock and scratch it as hard as you can against the other. Do this over and over until you form a powder.”

Morgan and James each put their flat rock on the ground. They held it steady with one hand and rubbed the sharp rock back and forth on it. Meanwhile, Rick also rubbed his two rocks together.

After a minute, Rick stopped and caught his breath. He looked at Morgan and James, still working away. “Okay. That looks good.” The twins carefully picked up their rocks and stood.

Rick turned to the group. “What we’ve just done on a very small scale is what glaciers do.” Rick glanced at Morgan and James. “Rub your hand over the scratched area on the rock.”

All three of them did this. “Now, let’s hold up our hands.”

Morgan, James, and Rick showed their palms. A fine powder covered their skin.

“One cubic foot of glacial ice weighs nine times more than the same size block of regular ice or snow because the glacial ice is compressed. And when glaciers move, they grind the rock underneath them into a rock flour like we just made. That rock dust is so light, it floats in water. When sunlight shines through it, it causes glacial lakes and streams to have a turquoise color—just like this lake and the larger Grinnell Lake below.”

“Hey, we saw a little bit of that at Avalanche Lake,” Morgan whispered to James.

“How about a hand for our glacier simulators here!” Rick called out, and everyone clapped as Morgan and James walked back to their parents.

Rick wrapped up his talk: “This awesome glaciated place won’t have these glaciers much longer. Global warming is changing all that. But we’ll still call it Glacier because of the scenery the glaciers created. Thank you for joining me on the hike. If you go back on your own, just remember to warn the bears along the way.”

Dad looked at his family. “Let’s hike down with the group,” he said, giving the kids a wink.

The grizzly huffed along, climbing far above the trail. A large pile of sand and pebbles piqued her curiosity. The bear lumbered over and noticed tiny black insects scampering out of a hole on top of the mound

.

The bear stuck her nose into the hole and licked up a bunch of ants. Then she furiously

pawed at the top of the massive colony. A flurry of ants rushed out of their disturbed home. The grizzly lapped up as many as she could. Some of the ants managed to find their way onto the bear’s face and fur. A few trickled into her nose

.

The grizzly hopped back and shook her head vigorously. She swatted at her nose several times, then sneezed and huffed while backing farther away from the mound. She shook her head and rubbed her nose on the ground. Finally, the bear rolled her face and body onto a nearby pile of dirt

.

Somewhat relieved, the grizzly stood up and shook her whole body. She glanced at the ravished ant mound and lumbered away

.

The Parkers chatted with Rick on the way down. When they reached the junction to Grinnell Lake, Morgan, James, Mom, and Dad said good-bye.

Soon they had left everyone behind and the Parkers were alone, hiking in a dense forest. Dad led the way. “Hey, bear!” he called out while trying to imitate Rick’s deep voice.

They saw people ahead of them, and the Parkers purposely caught up. Now nine people snaked their way through the forest toward Grinnell Lake.

Someone in the front stopped. “Look out up here,” she warned. The

woman stepped cautiously over a large pile of fresh scat and shouted, “Bears! We’re coming through!”

Morgan glanced at the scat as she walked by. She noticed tiny pieces of red berry scattered throughout it.

They reached a footbridge hanging low over a stream. One by one they crossed the swaying bridge and gathered again on the other side.

Finally a clearing appeared between the trees. Morgan, James, Mom, and Dad walked onto a sandy shoreline. Straight ahead of them was jewel-like Grinnell Lake.

The Parkers sat down next to the water. James quickly pulled out his journal.

This is James Parker reporting.

I’m sitting here at Grinnell Lake in Glacier National Park. This lake and the one above are different from others. They’re turquoise because of Grinnell Glacier.

But it’s not just the water color that makes this lake fantastic. There’s a huge waterfall across the way that comes from the glacier. And there are incredible mountains all around us. Rick said Native Americans called Glacier’s mountains “the backbone of the world.” Now I can see why.

What’s really sad, though, is that the color of this lake will change back to normal in about ten years. That’s when Grinnell and all of the park’s other glaciers are expected to have melted away due to global warming.

But it’s still exciting seeing glaciers, and we’ve gotten a good look at five so far: Piegan, Sexton, Gem, Salamander, and Grinnell.

Speaking of exciting, we have Dad’s little surprise coming up soon. I don’t think he has any idea it’s coming!

Reporting from Glacier,

James Parker

After a few more minutes at the lake, the Parkers packed up. They returned to Lake Josephine and stopped at the junction.

Mom turned toward her family. “Do you want to hike back the rest of the way or take the boat?” she asked.

The family thought about the bear they saw earlier in the day and the scat on the trail.

“Let’s take the boat,” James blurted out.

“Definitely,” Morgan added.

Later that evening, after cooking dinner at their site at the Many Glacier Campground, the family walked over to the nearby Swiftcurrent Motor Inn store. A large group of people were gathered in the parking lot with binoculars and telescopes.

Rick was among them. He saw the Parkers. “Hey, it’s my buddies from Grinnell Lake! How was the rest of the hike?”

“Fine,” Morgan replied.

“No bears?”

“Only scat.”

Rick pulled a pair of binoculars off his neck. “Do you want to see a grizzly now?”

“Yes!” Morgan exclaimed. She took the binoculars first. “Look at that grassy slope halfway up the mountain,” Rick directed. “To the right of a tree is a small brown dot. But it’s moving.”

Morgan scanned the area where Rick pointed. “There it is!” she called out.

“There’s also a cub nearby,” Rick mentioned.

Morgan passed the binoculars to James. James focused in. “The cub is just below the mom,” he reported.

After Mom and Dad took a turn, they handed the binoculars back to Rick. “Now that’s the way to see a grizzly,” Dad said, “from a nice, safe distance.”

The Parkers said good-bye to Rick and then strolled over to the store for some ice cream.

Mom and Dad clipped the bear spray canisters

they had purchased the night before to their belts. The family gathered their lunch and water and walked to the nearby parking lot. At the end of the lot was the Iceberg Lake Trail.

The Parkers began their early morning hike on a worn pathway.

As the family walked along, they heard dogs barking.

Dad stopped and looked around. “That’s weird,” he said. “Dogs are usually not allowed on national park trails.”

Farther up the trail was a ranger with a large group of people. They were all gazing into the brush. Suddenly the group gathered close together. A moment later they began coming down the trail toward the Parkers.

The family watched the line of people hastily descend. The ranger spoke into a handheld radio as he walked.

The first person in the line of hikers approached the Parkers. “They’re closing the trail,” he reported.

“How come?” Mom asked.

“We just got bluff-charged by a grizzly. Apparently there’s also a mother and her cubs farther up the trail.”

Morgan, James, Mom, and Dad filed into line with the others. They hiked out with the large group, eventually spilling into the parking lot. Three people with dogs on leashes were at the trailhead.

“I guess there

are

dogs out here,” Morgan said.

The Parkers stopped and waited for the ranger, to ask him what was going on. Finally he approached from the back of the line. Morgan was the first to realize it was Rick.

“Hi!” she greeted him.

Rick waved, then stopped to put down his pack. He took out a sign and posted it at the trailhead.

D

ANGER

: T

HE AREA BEYOND THIS SIGN IS CLOSED DUE TO BEAR ACTIVITY

.

Mom stared at the ominous message. “I’m glad we got the warning!”

“We’ve been monitoring this trail all summer,” Rick explained. “It’s prime grizzly habitat, and the buffalo berries are ripe. We’ve had to close it before, and I’m sure we’ll have to again.”

“How long until it’s open again?” Dad asked.

“That I’m not sure about. We’ll need at least three days of grizzly-free trail first.”

Rick looked at the people with the dogs. “I’m glad you and your canine friends were still around,” he said to them. “Are you ready for some bear conditioning on the Iceberg Lake Trail?”

A woman in front nodded. Rick, the dogs, and their guides hiked up the closed trail.

The Parkers walked over to the bench in front of Swiftcurrent Motor Inn. They sat down and looked out at the parking lot. “I wonder what they’re going to do with those dogs?” Dad pondered.

After a few minutes, James looked at his family. “Well, since we can’t hike here, what do you want to do?”

Mom pulled out a park newspaper and sifted through it. “Hmm. This could be interesting.” Mom explained her idea.

“That does sound like fun,” Morgan, James, and Dad agreed.

The Parkers walked over to their campsite. They put the bear spray in the bear locker and drove out of the park. At the junction, Dad turned

north and they were on their way to Canada.

The highway paralleled the park. Soon, a solitary, square-sided mountain dominated the view. “That’s quite a peak,” Dad commented.

James searched for the mountain on his map. “It must be Chief Mountain,” he reported.

• • •

The dogs sniffed around a large paw print in a muddy section of trail. They picked up a scent and started following it.

Soon, the dogs and their trainers came upon a large, solitary grizzly foraging nearby. The dogs barked furiously and tried to rush at the bear. The guides held the dogs in place and watched.

The grizzly heard the commotion and looked up.

One of the guides called out brazenly to the grizzly: “Hey, bear. Go on, bear. Get out of here.”

The bear stared at the group. Then it continued searching for food.

One guide led the group a few steps closer. She commanded, “Bear, you get out of here now.”

Still the bear was slow to move. The woman turned toward Rick. “It might have gotten human food somewhere around here in the past. It’s harder to work with food-conditioned bears.”

Rick looked concerned. “That’s unfortunate.”

While the dogs barked incessantly and kept their leashes taut, the guide called out again, but the bear stayed in the vicinity.

“Well, here’s our next step,” one guide said. She pulled out a special rifle and checked to see that it was loaded. Then she aimed the weapon at the ground below the bear. “Okay, here goes.” The guide shot several rubber bullets near the bear.

The bear took off and rambled into the bushes until it was out of sight.

“Good bear!” the guide called out. She immediately turned to the dogs. “Okay, quiet now,” she commanded, and the dogs became silent.

Rick turned to the group. “What next?”

“We keep on conditioning the bear until it no longer needs dogs or rubber bullets to avoid humans,” the guide explained. “Their reward is to get away from the chaos we bring them. I’m confident this training will work.”

The group watched the spot where the bear disappeared. “Let’s check again later,” a guide said, and they trotted down the path, looking for other bears in the area.

BEAR SHEPHERDING

The Wind River Bear Institute in Montana trains and works with Karelian bear dogs to help teach bears in Glacier and other areas to avoid humans. They call this bear shepherding. The purpose is to make wilderness areas where people and bears cross paths safe for humans. In the long term, this is also best for the bears. By using dogs, voice commands, and at times rubber bullets or firecrackers, institute members teach the bears that humans are a nuisance and should be avoided. The bears are taught to leave an area only when humans are around; they can return to feed later. Karelian bear dogs have been used since 1996 in wilderness areas in hundreds of situations. No dogs, humans, or bears have been hurt in the process.

Eventually the Parkers went through customs and entered Canada. They wound their way into Waterton Lakes National Park, Glacier’s twin park in Canada.

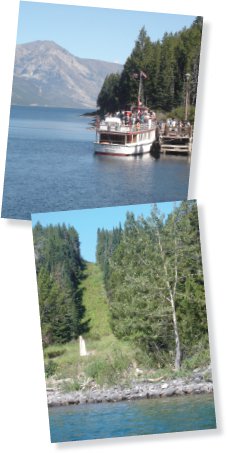

Dad drove into town and found the marina. He parked the car, and the family climbed out. They got tickets and found their seats just as the ferry left the dock.

After a while, a person spoke into the sound system. “Welcome to Waterton Lake,” the guide announced. “We’re on the largest of Waterton’s

three main lakes and the deepest lake in the Canadian Rockies. Waterton Lake is 487 feet deep.

“Waterton-Glacier is the world’s first International Peace Park. The two parks joined to become a peace park in 1932.”

The boat slowed to a stop right in the middle of the water.

“Look at the mountains on each side of the lake,” the guide directed. “See anything unusual?”

James noticed a strip cut out of the forest.

What happened to the trees?

he wondered.

“Welcome to the 49th parallel,” the guide said. “And back to the United States. The trees are cut along the border every fifteen years, all the way to the ocean.”

“So we’re back in Glacier now,” Morgan realized.

The boat sped up and continued cruising. A short time later it slowed down again as it approached Goat Haunt, then docked. The Parkers got off the boat with the rest of the visitors. They all proceeded down an asphalt trail toward a ranger station. A US park ranger met everyone there, checked IDs, and asked some questions before letting them back on US soil.

The Parkers waited by a sign with a small group of others. “I like this guided walk thing,” Mom said. “We learn about the park, and we don’t have to fend for ourselves in bear country.”

Ranger Lynn Dixon trotted up and introduced herself. A moment later the small group was hiking toward Kootenai Lake.

Lynn set a brisk pace on the mostly flat trail. A short time in she

stopped and let everyone gather around. “Notice this pile of pulpy, dry nuggets. Does anyone know what animal did this?”

“Elk?” James wondered.

“Deer?” Morgan asked.

“Moose,” Lynn answered. “We’re on the trail of the moose. You’ll see why soon.

“This scat is from last winter. The moose eat almost all wood then, because sticks and bark are about all they can find above the snow.”

Kootenai Lake.

A few minutes later Lynn stopped again. “Moose,” she informed the group, “actually crossed over the Bering Strait from Asia about 150,000 years ago. They settled in Alaska, Canada, and Maine—all areas above the 50th parallel. We’re at the 49th here. They began to inhabit this area 150 years ago. Does anyone know why?”

Nobody had an answer.

“They came on their own,” Lynn answered. “They moved into these ‘spruce-moose’ forests, or so we call them, where forested areas had been cleared by logging and beavers had built dams. The dams made marshes and lakes that moose love.”

The group hiked farther down the trail. At one point, Lynn turned and said, “Male moose can have antlers up to six and a half feet wide. Those antlers are the fastest-growing bone in the world, growing up to a half inch a day! Moose can also weigh up to 1,200 pounds. They have powerful legs that move straight up and down when they run. That might make them have an awkward gait, but it also helps them pull up out of the snow. And there’s plenty of that around here in the winter. Moose can

also withstand temperatures down to −48 degrees! The hollow hairs that make up their shaggy fur keep them warm.