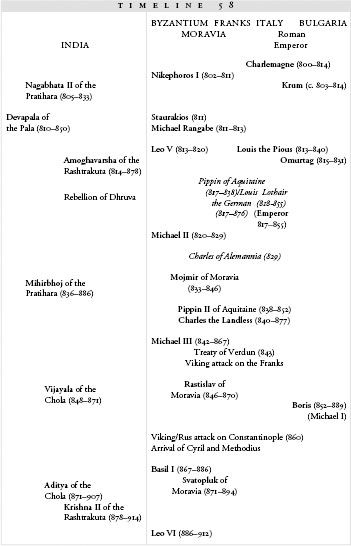

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (59 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

At some point, Basil also began sleeping with his wife, since she bore him two more sons after Michael’s death. (Basil, understandably, displayed a marked preference for his younger sons over his oldest.)

In 886, Basil was hunting with his attendants when he rode out ahead of them to pursue a huge stag. The animal turned on him; Basil’s horse bolted and threw him onto the stag’s antlers, and the stag dragged him through the woods until one of his guards caught up with him and cut him loose. Basil, badly wounded, had just enough strength left to accuse the guard of trying to kill him with the drawn sword the man had used to free him; he ordered the guard put to death, and died not long afterwards. Only the introduction to his great Purification was ever published.

10

When Basil’s entourage returned to Constantinople with this story of his death, it was greeted with skepticism. More than one chronicler suggested that it was covering up some sort of assassination plot, perhaps directed by Basil’s son Leo. Relations between the two had grown sourer as Leo grew, which merely fed the rumors that Leo was actually the son of the dead Michael.

But Leo was never publicly accused of Basil’s death. He was crowned emperor. Shortly afterwards, he had Michael’s body exhumed from its burial place in a monastery outside of Constantinople and reburied in Constantine the Great’s own mausoleum.

11

Between 861 and 909, Turkish soldiers take control of the Abbasid caliphate, new dynasties break away in the east, and a new caliph proclaims himself in Egypt

I

N EARLY

D

ECEMBER OF

861, the Abbasid caliph was murdered.

The murder of a caliph was not anything new or startling. But by 861, the surface tension that held the Islamic world together was already strained by crosscurrents of doctrine and practice, and this particular assassination strengthened those currents until the surface unity finally, and fatally, burst apart.

The chain of events that led to this particular murder had begun back in the early years of the century, with the caliph al-Mamun himself. Before his death in 834, al-Mamun had developed a particular interest in a form of doctrine known as Mu’tazilism, which suggested that he had the responsibility to purify the community—by force, if necessary.

The Mu’tazilites believed that God was perfect reason, which meant that his divine judgment of men, both sinners and righteous, was also completely rational. In Mu’tazilism there was no uncertainty about God’s intentions. There was no need to appeal for mercy: mercy required the giver to change his mind about the severity of an offense, and God did not share in such human qualities as changing one’s mind. God was so completely transcendent, so far beyond the limitations of man’s existence, that he was almost an abstraction: Divine Logic.

1

Like all medieval (and modern) arguments about the nature of God, this one had a political application. Mu’tazilite leaders argued that since men have the ability to reason, they can think their way to a clear understanding of right and wrong: they can predict, with certainty, what God’s judgment on their acts will be. They may not always choose the righteous act, however; and so it is the leader’s job to guide the community in right belief and right practice.

*

It is also the leader’s job to stamp out wrong belief and evil practice, and al-Mamun had taken this task quite seriously. He instituted an inquisition: the

mihna

, or ordeal. Teachers, scholars, and leaders were subjected to intense questioning, which sometimes involved quite forceful persuasion, until the interrogated were “convinced” that Mu’tazilite ideas were true.

2

In many cases, the conviction was shallow; agreeing hastily to the doctrines that al-Mamun decreed improved the chances of quick release from his prisons. But al-Mamun, who died just as his inquisition was getting underway, did not quite grasp this truth. He left orders to his half-brother and heir al-Mutasim to continue the inquisition, convinced that it would not only make the Islamic community stronger but also bolster the power of the caliphate.

Unfortunately al-Mutasim, carrying out his brother’s wishes, ran slap into another difficulty. Mu’tazilite doctrine assured him that as caliph, he had the authority to reward good and punish evil (and to define what good and evil

were

). But he ruled in a world where Muslims were increasingly divided over who could claim the right to be the true caliph, the rightful leader of the community.

The arguments about who should be caliph had been going on for two centuries. Many Muslims still believed that the Islamic world should be led by a direct descendent of the Prophet. They had hoped, since the death of Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali back in 661, to see a descendent of Ali and his wife, the Prophet’s daughter Fatima, become caliph. Instead, the caliphate had been taken over first by the Umayyads and then in 750 by the Abbasids, who traced their descent back to Muhammad’s uncle but not to Muhammad himself. At both crises of leadership, the supporters of Ali—the Shi’a—had called for a caliph of Ali’s blood.

Neither time had their voices been strong enough to triumph against the majority, known as the Sunni. So the party of Ali, rejecting the caliphs as illegitimate, had exalted its own series of leaders: not caliphs, but

imams

, religious leaders who refused to swear allegiance to the caliphate. The Shi’a (a relatively small group who lived within the Sunni majority, sometimes peacefully, sometimes in a state of minor war) were willing to obey their

imams

without question. They believed that the Prophet himself had

designated

his successor, and that each

imam

had the God-given, infallible knowledge that allowed him to designate the

next

successor. The

imams

could not make mistakes, because they were filled with the wisdom of the Divine.

3

But the Abbasid caliph could not boast the same kind of authority that the Shi’a granted to their

imams

. Sunni Muslims

chose

their caliphs; the pool of candidates was limited to the Abbasid line, but the caliph himself was elected by the community. Which was a problem for al-Mutasim, because while God and the Prophet were incapable of error, the community of Muslims might realize, after electing a caliph, that they had blundered.

And if a caliph started arresting and torturing members of the community who disagreed with him, it was very likely that the community might decide that he was a mistake sooner rather than later. During his caliphate, al-Mutasim had to put down three separate major revolts and a handful of minor ones. It became very clear that if the caliph were to hold on to his power, he needed an army that came from

outside

the community—an army that would fight for him but had no right to remove him from power in favor of another candidate.

4

Al-Mutasim formed this army around the core of his own personal guard—captives who had been brought back to Baghdad after wars with the Western Turkish Khaghanate and the other Turkish tribes across the Oxus river. These Turkish captives had become slaves to the Abbasid caliphate, and many of the slaves were trained to be soldiers in the Abbasid army. Those who did well were often set free, and some were even given government offices to hold.

The influx of Turks into Baghdad had been constant, over the last century of warring, and al-Mutasim had a personal guard of four thousand Turkish slave-soldiers even before he became caliph. As caliph, he began to transform this guard into a real army. Within just a few years, he had expanded his force until he had seventy thousand men under his control—mostly Turks, but also a few Slavs and North Africans who had been captured in battle and brought to the capital as slaves.

5

These men, chosen for the specific reason that they were outsiders, now surrounded and protected the caliph, pushing his Arab and Persian officials to the edge of the inner circle. Resentment grew in Baghdad. Continual scuffles—and worse—broke out on the streets between Turks and the men they had supplanted. Finally al-Mutasim decided to move his capital to another city: north along the Tigris to Samarra, where he constructed separate quarters for his Turks and kept them isolated from the population. This prevented street riots, but it also transformed the Turks into a highly cohesive, self-contained community that had no particular loyalty to Muslim doctrine. Al-Mutasim was succeeded first by his older son and then by his younger son al-Mutawakkil, both of them living in Samarra. During the caliphates of both, the Turkish community strengthened until the Turks were the single most powerful segment of Abbasid society.

6

In 861, all of these tensions came to a head when the caliph al-Mutawakkil threatened to disinherit his oldest son al-Muntasir. The young man went to the Turks and persuaded them that they would prosper better under

his

rule than under the rule of any of his brothers. Before al-Mutawakkil could carry through on his threat, his Turkish guards murdered him in his own quarters and arrayed themselves behind al-Muntasir’s election as the new caliph.

Al-Muntasir died of illness shortly after his ascension, and the Turkish army picked the next caliph as well. When he displeased them, they tried to depose him. He fled to Baghdad and barricaded himself inside the city; the Turks laid siege to the old capital and, after a year, forced the powerless caliph to abdicate and chose a new one. Baghdad, now under Turkish control, became once again the political center of the caliphate.

Brought from the outside to protect the power of the caliph, the Turks had become kingmakers. The newly chosen caliph, al-Mutazz, lasted only three years. In a massive miscalculation, he spent too much money on his court and ran out of cash to pay his army. Once again the Turks intervened. Al-Tabari preserves an eyewitness account of what happened when they dragged the twenty-four-year-old caliph from his palace:

I thought that they had already beaten him with clubs, for he came out with his shirt torn in several places and traces of blood on his shoulders. They stood him in the sun in the palace at that time when the heat is oppressive. I saw him lift his foot time and again due to the heat of the place where he had been made to stand. I also saw some of them slap him, as he tried to protect himself with his hand…. After he had been deposed, he was reportedly given over to someone who tortured him, and he was forbidden food and water for three days…. Finally they plastered a small vault with heavy plaster, put him in it, and shut the door behind him.

7

By the next morning, the young caliph was dead. The Turks were in power, and one thing had become perfectly clear: the Abbasid caliph might claim to be God’s spokesman, but that claim would no longer protect him.

The loss of control over the palace at Baghdad was mirrored by the caliphate’s loss of control over the eastern reaches that had once belonged to the Abbasid empire.

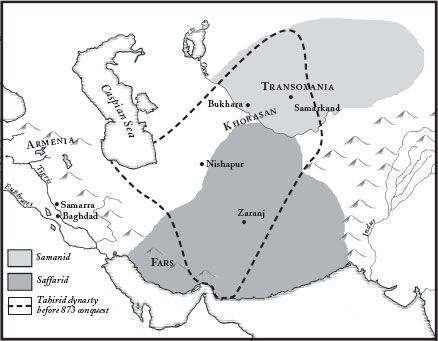

The Tahirids of Khorasan, descendents of the general Tahir, were still ruling over the territory that had been given them by al-Mamun half a century earlier. But their power was soon shaken. In 867, a coppersmith turned bandit named Ya’qub-i Laith Saffari began conquering a territory south of his home city of Zaranj, halfway between the Tigris and the Indus. The Tahirids tried to defend their realm, but by 873, Saffari had fought all the way to the Tahirid capital city Nishapur. He captured the young Tahirid ruler and took the city for himself. The Tahirid dynasty was shattered; it had lasted only seventy years.

59.1: The Saffarid and Samanid Dynasties

Saffari then began to advance towards Baghdad, intending to storm the city and force the caliph to grant him official recognition as a legitimate Muslim ruler. The caliph, of course, was more or less powerless; the Turks had put another handpicked candidate, al-Mutamid, into the caliphate, and he would survive for twenty-two years by allowing his officials and army to control the palace. But although the illusion of a God-ordained caliph was flickering, it was still functioning. Even as he built his own separate empire, Saffari wanted the caliph’s stamp of approval.

8

The chaos of the last twenty years made the most straightforward solution—sending an army large enough to wipe out Saffari’s rebellion—impractical. Instead, the caliph’s officials set out to find an ally who could help by pressuring Saffari on the other side. A message was sent to the city of Samarkand on the far side of the Oxus river, offering the governor there the title “Ruler of Transoxania” if he would rally his forces against Saffari.

This governor was named Nasr, and he too was worried about Saffari’s expanding power. His family, the Persian clan of the Samanids, had been governors of Samarkand since 819, and for some years they had been the strongest power east of the Tahirids. Now that the Tahirids were gone, Saffari would likely turn on the Samanids in the future.

Nasr agreed to the caliph’s proposal, and the Samanid family became rulers of Transoxania. Led by Nasr’s brother Ismail, the Samanids began to fight against Saffari from the northeast, while the Turkish army, in the name of the Abbasids, erected defenses in the west.

In 876, the Turks and Abbasids won a victory against Saffari’s men, halting the advance towards Baghdad. They also recaptured the young Tahirid ruler Muhammad, who had been held prisoner by Saffari’s army for the last three years. They sent him back to Khorasan so that he could try to take up the governorship again, but his power was shattered, his authority gone; he was unable, even with the help of Turkish forces, to recapture the land he had lost to Saffari.

His weakness offered the Samanids the chance to do some empire-building of their own. In 892, the Samanid ruler Nasr I died and his brother Ismail, who for some years had been the actual power behind the Samanid throne, took control. He established his own military headquarters in the city of Bukhara and began to expand his control across Khorasan. Now the far reaches of the Abbasid empire had been chiselled away to almost nothing. Instead, the emirs of two independent dynasties, the Saffarids and the Samanids, claimed the east.

Back in Baghdad, the parade of caliphs through the throne room continued. Al-Mutamid was succeeded in turn by his nephew, his nephew’s half-Turkish son, and the son’s son; the names of the caliphs are irrelevant, since power during that quarter century was held by the royal guard and the court officials. The post of senior

vizier

—literally, “helper” to the caliph—accumulated more and more power, until the vizier’s authority was as great as any caliph’s of the past.

9