100 Mistakes That Changed History (12 page)

The two armies met near Adrianople and camped in sight of each other. It was agreed that Valens would send a delegation into the ring of wagons that formed the Visigoths’ camp. Remember, this was a movement of the entire Visigoth people, and in that camp were not only warriors but also families. Each side, not without cause, watched for betrayal and formed up their horsemen, ready to attack as needed. But Fritigern seems to have been more than ready to talk peace. Then a small mistake doomed Rome.

As the Roman delegation rode toward the Visigoth camp, they had to be nervous. Their side had just used a similar maneuver in an attempt to assassinate the very leaders they were riding to meet. Around them, thousands of horsemen armed with bow and lance stood poised to attack one another. For months, both sides had been fighting small, bitter battles and rarely taking prisoners.

Maybe it was in response to some sort of unusual movement on the wall of wagons as the Romans approached. Or maybe he saw an old enemy. One of the soldiers, who was acting as the bodyguard for the Roman delegates, fired an arrow, one arrow only, toward the disturbance. The other guards may have fired then as well. None survived to say if they did or did not. The Visigoths reacted with a shower of arrows. Most of the Roman delegation fell, and the survivors fled.

Seeing this, the Roman cavalry charged the Goths’ camp from their position on both flanks of the infantry. The horsemen were unable to break into the Visigoth camp they surrounded. The bulk of the Visigoth and Ostrogoth heavy cavalry, well-armored men on fresh horses, had returned late. They had been waiting out of sight, behind a small wood, to one side of the battlefield. These armored horsemen charged first one, then the other force of Roman cavalry. Assailed by arrows from the wagons and attacked from behind by thousands of armored warriors, both groups of Roman horsemen fled. This left the still-unformed and badly trained Roman infantry at the mercy of the entire Gothic army. About 40,000 men died, and the power of the Western Roman empire was broken forever. Roman armies became less and less Roman and more and more barbarian. The vaunted infantry of the legions was shown to be gone. Rome never again ruled more than parts of Italy, and within a century, the city of Rome itself had fallen twice and the barbarian Odoacer held the meaningless title of emperor.

If that one arrow had not been fired, there was a very good chance that peace could have been achieved. It was the Visigoths, who had valid claims and concerns, who had asked to talk, and it was very much in Valens’ interest to have them as allies and not enemies. Without the disaster at Adrianople, Rome would have remained stronger and much more capable of defending itself. A Rome that still had a real army with Gothic allies might have maintained the high level of culture and literacy the Romans and Goths shared. The centuries that followed the Battle of Adrianople are described as the Age of Barbarians and the Dark Ages. Except for one arrow fired by an anonymous bodyguard, those times might have been much less barbarous and far less dark.

21

HIRING OUT HOME DEFENSE

We Are Here to

Help You . . .

425

S

ometimes the enemy of your enemy is just your enemy too. In the early part of the fifth century, Roman occupants withdrew from Britain to defend Gaul and Italy from the invading barbarian tribes. They left behind a defenseless land with an uncertain future. The lack of a strong government and military presence sent the country spiraling into chaos. Bands of Picts, who dwelled on the north side of Hadrian’s Wall, began raiding villages on the south side. They took food, slaughtered countless Britons, and robbed the local homes and churches. Without the support of the Roman legions, British chieftains felt they could not stop the plundering and raids. So, they hired Saxon mercenaries to come over and quell the troublesome people of the north. They soon learned to regret their decision.

Not much is known about the details concerning the events, but according to tradition and the Venerable Bede, the story goes something like this . . .

In about 425 there lived a king named Constans, who had as his most trusted adviser the lord Vortigern. The king had lived his life in a monastery and therefore knew nothing of the affairs of state. So Vortigern managed the country on his behalf. It didn’t take long for Vortigern to figure out that if he ran the country, he might as well be king. He concocted a plan to usurp the throne from the pious King Constans.

Vortigern first persuaded the king to put the treasury in his care and then asked for control of the cities and their garrisons. He convinced the king that the Picts planned to invade and would be aided by the Norwegians and the Danes. Vortigern told Constans that the best way to avoid this would be to fill the court with Picts who could act as spies against their own people. The real reason Vortigern wanted to pack the court with Pictish nobles was that he knew they could be easily bought. When they arrived, Vortigern treated them with favoritism. Once he had their loyalty, he told them that he planned on leaving to seek his fortune, as he could not live off of the measly allowance the king provided him. The outraged Picts decided to take action against the king. They broke into his bedchamber and cut off his head. Vortigern played the part of the grieving friend well. He ordered the execution of all involved in the crime. This played well with the Brits, but when word got north to the Picts, they wanted revenge.

Vortigern not only had to contend with the fact that he had made an enemy of the Picts, but he also had made an enemy of Constans’ two brothers, Aurelius Ambrosius and Uther Pendragon. (They both had fled to Brittany, but returned to play a part in the story later.) Hengist and Horsa, two Saxon leaders, appeared off the coast of England in what likely was supposed to be a raid. The Saxons landed in Kent with a band of fully armed warriors. Rather than gathering men to repel their invasion, Vortigern saw this as an opportunity. He invited the two Saxon bands to fight for him in exchange for land and money. It seemed like the perfect match.

Together, the trio won many victories over the Picts, and in return Vortigern granted Hengist land in Lincolnshire. Hengist told Vortigern that to keep the enemy at bay he must send for more men from Germany. He was given permission to do so. As if that were not stupid enough, the king also made Hengist an earl and allowed him to build a castle stronghold. The newly appointed earl named his castle Thongceaster.

If you think Vortigern acted foolishly so far, just wait. It gets worse. Vortigern fell in love with Rowena, the beautiful daughter of Hengist, and asked for her hand in marriage. Hengist agreed, but only if the king would give him the county of Kent to compensate for his loss. All involved totally ignored the fact that Kent already belonged to Earl Gorangon, who was also sworn to Vortigern’s service and must have been furious. Vortigern then appointed his newly acquired father-in-law as his chief adviser. He also gave Hengist’s sons land between Hadrian’s Wall and the southern part of Britain as a buffer between the raiders and his own people. While all this was happening, the number of Saxons settling in Britain increased daily. They owed loyalty only to Hengist. It became clear to every Briton except Vortigern that Hengist planned to take over.

When the British nobles voiced their concerns to Vortigern he ignored them. But if things continued, the nobles realized they would lose all of their lands to the Saxons. So, they declared Vortigern’s son Vortimer their king. Vortimer immediately set about driving the Saxons away. He fought and won many battles. In one of those battles, Horsa, the other leader who had arrived with Hengist, was slain. Many Saxon warriors had to flee back to Germany, often leaving their women and children behind. The family members left behind were usually enslaved. Soon all of the Saxon warriors and leaders were back across the Channel. Upon hearing of all this, Rowena decided to take revenge on Vortimer and had him poisoned. When news of Vortimer’s death reached Hengist, he raised an army and set sail back to Briton. When he arrived, he sent a message to Vortigern, who was king again. Hengist told him that the army had been brought over to deal with Vortimer, and he claimed he was unaware of Vortimer’s death. The two leaders arranged to meet with their top barons at Amesbury Abbey to negotiate terms. Tradition was that no one brought weapons to a negotiation. The British nobles obeyed the tradition, but the Saxons did not. Once the meeting had begun, Hengist and his men pulled out their daggers and cut the throats of the unarmed Britons.

At this point, the story slips into legend, with tales of Merlin the wizard woven throughout. Vortigern did not die in the massacre, but was killed later by Ambrosius, the exiled son of Constans. The legend does have a ring of truth to it, if only a literary one. It conveys the feelings of betrayal that the Britons felt toward the Saxon invaders, and it provides archaeologists and historians with a possible explanation for the sudden shift of power and the mass migration of the Saxons. The tale also offers a moral. So for all you men and women out there with plans of world domination, take a lesson from Vortigern, not to mention Rome: Never hire someone to fight your enemies. And if you do so, don’t allow them to achieve greater strength in numbers. The leader with the biggest army almost always ends up as king.

22

BLIND OBEDIENCE

Another Time

771

I

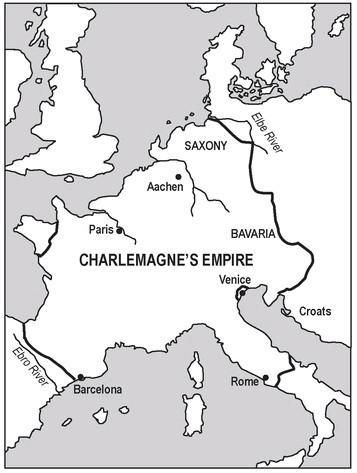

n many ways the European Union is an attempt to set the clock for Europe back just over a thousand years. In 771, Charles became the sole king of a relatively small German kingdom whose capital was Aachen. In fifty-three military campaigns, and by having the distinction of being one of the most competent administrators in history, he was able to carve out an empire that was larger than anything Europe had seen since Rome. He worked hard all his life to create a prosperous and united kingdom, generally succeeding. Literacy grew, and the economy of central Europe, including today’s Germany and France, surged. But law and tradition waited to doom the first united Europe.

The law that put an end to one of the brightest periods in the Dark Ages was a long tradition that attempted to deal with the often murderous rivalry between the heirs of a king or other noble. This law decreed that any kingdom or noble’s holding was to be divided between all of the sons of a king. This may help minimize the rivalry between siblings, but it also meant that large viable kingdoms and fiefdoms were split and split again.

This was going to happen to Charlemagne’s empire on his death, but all the possible heirs except one, Louis, died before their father. So Louis became the sole ruler of the empire and also did a good job of ruling. Unfortunately, he also did an equally good job of begetting sons. His three, Pepin, Lothair, and Louis, all proved ready and anxious to inherit their third of the kingdom. They even accepted that they would have to share with their two brothers. But in 823 Emperor Louis’ second wife had a fourth son, Charles. When Louis tried to change his will so that the new son got a fourth part of the empire, the older sons organized a revolt within the palace. The conflict simmered and likely threatened to become open civil war. Louis tried to meet with Lothair, hoping to restore their relationship. When he arrived at the meeting place, all three of the older sons were there with their supporters. They forced Louis to abdicate. At this point, the empire was split into three parts, never to be united again.

Had the law been different, with one son inheriting, the history of Charlemagne’s family might well have been bloodier and all of Europe much more peaceful. If his empire had not been split apart by a tradition that created rival kingdoms every generation, a united Europe might have been the norm. Millions of deaths could have been avoided if the wars between the nations formed from the pieces of his realm would not have been fought. The unity that the European Union strives for might well have been achieved a thousand years earlier. That law, created to keep peace within a family, was a terrible mistake for Europe, and the continent paid for it with a millennium of chaos and war.

23

BAD PRIORITY

Family over Future

1001

T

here are many descriptions of Vikings written around the year 1000. Perhaps the mildest of them described the fearsome Norsemen as violent and impulsive. Most use very graphic and negative terms, which are used today to describe psychopaths and worse. Basically, the Vikings’ main pursuit for over two centuries was raiding, plundering, and taking over other people’s lands. The land stealing becomes more understandable if you consider the poor, rocky soil and frigid weather that dominates Scandinavia. So it took a real effort to stand out among the Vikings as being the most violent of them all. But one Viking was just that, and he was banished twice, until he ended up living at the far western edge of the entire European world. This Viking was called Eric the Bloody. Eric the Red is the more tempered translation, which is suitable for consumption by schoolchildren. Eric the Bloody managed to get himself banned to remote Iceland and then from all but a corner of that small island. But even after killing several neighbors in what should have been easily settled disputes over boundaries, the man had enough charisma to gather a group of followers and lead them even farther west. They settled on an island he called, more for good PR than reality, Greenland. The name stuck.