100 Mistakes That Changed History (35 page)

74

BLINDED BY REVENGE

A Jettisoned Victory

1940

T

wo mistakes in August 1940 may have changed the entire war that followed. One was made by the lead aircraft in a small flight of Heinkel bombers on August 24. It was night, and accurate bombing at night was difficult. In 1940, there was no GPS or any other way for a pilot to know where he was. The only available method was simply to follow landmarks. This was a dicey proposition on a dark night. Even in daylight, following any flight plan over enemy territory while being fired on from the ground and threatened by fighters was difficult. In the dark, it became incredibly easy to be dozens of miles off course. So it was not unusual for a flight of Heinkels, over blacked-out England, to go astray. The only real difference between the situation that night was that they had strayed over central London.

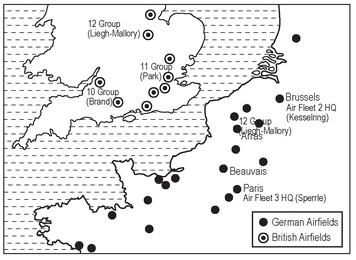

That was during the peak of the Battle of Britain. If Germany could gain air dominance, it could control the Channel and invade England. Their army had been shattered on the Continent and those who had escaped had left their artillery, tanks, and even weapons behind. The only thing protecting Britain from invasion was the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Royal Navy. But without control of the air over the English Channel, the ships of the Royal Navy would be easily sunk in the narrow waters. If that occurred, there was virtually no chance the battered Royal Army could hold the island against a determined German landing. Since August 13, the Luftwaffe had been constantly challenging the RAF. Their targets had been the RAF itself. German bombers had struck at the English airfields, aircraft production plants, and occasionally the strange radar towers along the coast. This forced the Hurricanes and Spitfires of the RAF to meet every attack or be destroyed on the ground.

The Battle of Britain

The German’s normal technique was to send over bombers protected by fighters during the day and unprotected bombers at night. The strategy was working. When the British fighters rose to attack the daytime bombers, the Nazi fighters could attack them. Since the RAF was outnumbered more than two to one in fighters, this created a steady attrition that favored the Germans.

In a message to the secretary of state for air on June 3, Winston Churchill stated that

the Cabinet were distressed to hear from you that you were now running short of pilots for fighters, and that they had now become the limiting factor . . . Lord Beaverbrook has made a surprising improvement in the supply and repair of aeroplanes, and in clearing up the muddle and scandal of the aircraft production branch. I greatly hope that you will be able to do as much on the personnel side, for it will indeed be lamentable if we have machines standing idle for want of pilots to fly them.

By August 19, a concerned Vice Air Marshal Keith Park commented during a heated debate as to whether the British fighters should go in as they arrived or form large formations and attack the German aircraft en masse, that the loss of planes and pilots had become so great it no longer was a pertinent question. He observed that a larger formation was still better, “but we are at moment in no position to implement it anyway.” There weren’t enough pilots left flying to use in any large formations. To the British, it was becoming clear that the Luftwaffe was winning what was later known as the Battle of Britain. And the Germans knew they were winning. Just the day before those Heinkel bombers wandered over London, Air Marshal Hermann Goering had ordered that the Luftwaffe was

to continue the fight against the enemy air force until further notice, with the aim of weakening the British fighter forces. The enemy is to be forced to use his fighters by means of ceaseless attacks. In addition the aircraft industry and the ground organization of the air force are to be attacked by means of individual aircraft by night and day, if weather conditions do not permit the use of complete formations.

So as things stood, with the RAF at the edge of exhaustion and running low on pilots, Operation Seelowe, the invasion of England, seemed inevitable. Then those few Heinkel bombers went off course. Not seeing their designated targets and deciding it was time to turn back toward their airfields in France, they did what they were supposed to do. They simply dropped their bombs without aiming at anything in particular. Without bombs it was easier for the aircraft to dodge enemy fighters. This clearing out of bombs was the common practice by both sides throughout the war. It just happened, unknown to the Heinkel pilots, that they were over London. The bombs themselves did little damage to the city, but the reaction was great.

After the German bombing of Rotterdam on May 15,1940, the official policy of the RAF became to bomb all military targets even when the target was located somewhere that guaranteed civilian casualties. But such bombings had been rare. Both sides had avoided bombing the other’s cities. But with the Germans seemingly beginning to attack London, this changed. The British reacted by sending up ninety-five RAF bombers who flew to the edge of their range. Their mission was to bomb Tempelhof air base. This base is located near the center of Berlin. Eighty-one of those bombers reached Berlin, but as was common throughout the war, their bombing accuracy was terrible, and that night, their bombs fell all over the German capital.

Goering, who had been bragging about how well the air war over England was going, was more than embarrassed. He had publicly and personally promised the citizens of Berlin that they would never even see a British aircraft over the city. Himmler had featured him making this promise on the radio several times in the weeks before the British reprisal raid. Adolf Hitler too was infuriated. In what seemed to have been an emotional reaction, they ordered the emphasis of the attacks on Britain to change from concentrating on the RAF to the bombing of London and the other British manufacturing and population centers.

By this time, most of the RAF coastal air bases had been rendered unusable. The RAF had plenty of aircraft, but was desperately short of trained pilots. The pilots they did have had been flying constantly for weeks and were exhausted. Some German bombing raids were beginning to get through without any aircraft intercepting them at all. Churchill’s valiant “few” were on the ropes and the count had begun. Britain was days away from losing control of the air over the Channel and England.

But the German decision, in reaction to the Berlin raid, changed everything. London began to suffer, but the pressure was off the RAF. While the German bombers wreaked havoc on London in the first days of what became known as the Blitz, the Royal Air Force’s pilots got needed rest, aircraft were serviced correctly, and new pilots were brought in. Air bases could be repaired and all of the radar stations put back on line. While the Battle of Britain continued for several more weeks, never again was the RAF so close to total defeat. By September, Hitler was forced to accept that an invasion of England was impossible.

If those Heinkel bombers had not mistakenly dropped bombs on London on August 24, it is possible that the Third Reich might have won World War II. The United States was not yet involved and would not be for more than a year. With England forced to surrender or be occupied, even if the United States had entered the conflict, there was no easy base near occupied Europe to stage an invasion from. More important, if the RAF, who had been days from collapse as an effective force, had been defeated and England forced to sue for peace, then the half million soldiers guarding western Europe would have been free to participate in the invasion of Russia a year later. With that many more men and tanks, the ability of Russia to survive those first months was questionable. Without them, German units penetrated to within fourteen miles of Moscow.

The Heinkel bomber pilots made an ordinary mistake following the standard procedure, by jettisoning their bombs without realizing London was below them. But the reaction of Hitler and Goering to the reprisal raid that bombing generated lost Germany the Battle of Britain and a chance to knock Britain out of the war. The prideful, emotional decision to change tactics to bombing London in August 1940 may well have cost the Nazis victory in World War II.

75

NOT PREPARED

Left out in the Cold

1941

T

he history of warfare has shown many times that overconfidence can kill, and this case of misjudgment killed hundreds of thousands. If anyone had a reason to be confident in 1941, it was the Nazis and Adolf Hitler. In 1939, Germany had overrun Poland in a matter of a few weeks. In 1940, France fell in just over a month. Not only did the Blitzkrieg ensure victory, but it seemed to guarantee a quick one as well. Then came Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of Russia. Attacking Russia, they bet everything. The consequences of failure, even failing to win a quick victory, are shown by history. But in 1941, Hitler considered himself a military genius and, so far, appeared to have lived up to the claim. All of Europe, from Poland to the Pyrenees, was occupied by Germany or was her ally. On June 22, 3 million German and allied soldiers attacked Russia. Somehow, mostly because Stalin refused to believe it was going to happen and executed those who disagreed, the Wehrmacht achieved surprise.

In the first months of the invasion, hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers were captured. In one case alone nearly 700,000 men surrendered or were killed when a large part of Ukraine was surrounded. Then it began to get cold, and a mistake that is very uncharacteristic of the meticulous planning normally attributed to the German general staff became apparent. The mistake was that Hitler and others were so confident of a fast victory, such as had occurred in Poland and France, that there had been no provision for equipping the army to continue fighting in the cold Russian winter.

Now, this means much more than a lack of overcoats and long underwear. Trucks and tanks were not winterized. The radiators would freeze up and even the diesel fuel took on a wax-like consistency in the subzero temperatures. Weapons froze solid in the middle of a battle and water-cooled machine guns became useless. On a personal side, there were no sleeping bags or insulated tents, so thousands of German soldiers literally froze to death in their sleep.

As quoted earlier, there is an old axiom that no battle plan survives contact with the enemy, but winter can be predicted. Through overconfidence or mistaking the open reaches of Russia for being similar to densely populated western Europe, no provision was made to keep the Wehrmacht fighting in cold weather. There were other factors that led to defeats, such as changing objectives and Hitler shifting panzer divisions around, creating delay. But the real mistake was not expecting another quick victory, but rather preparing for the invasion only under the assumption that all of Russia could be conquered in the few months before the notoriously fierce Russian winter arrived. That overconfident oversight meant that the German army could not fight at anywhere near its best level in the cold weather. It also cost the Wehrmacht tens of thousands of unnecessary casualties from frostbite or worse. Making the mistake of preparing only for the best of outcomes pretty much guaranteed the worst. If the German army had been properly equipped and prepared to continue fighting during the cold weather, they might well have captured Moscow and forced Russia to seek peace on Hitler’s terms.

76

IGNORING A WARNING

Intelligence Failure

1941

T

here are many questions about what exactly caused the disaster that occurred at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. By December 8, the questions as to who made what mistake and who failed to do what were being asked. After more than sixty years and dozens of books, the questions are still being asked. The result of this great mistake is simple to define. The U.S. fleet and U.S. Army air corps airfields were not ready for the attack. They were set up in such a way as to be almost as vulnerable as possible. Unless a lot of people wanted to see the U.S. Pacific fleet slaughtered, and they did not, a mistake occurred that ceded control of the Pacific for months.

The commanding officer of the Pacific fleet was Admiral Kimmel, and General Short commanded the army air bases. The air force was not yet a separate branch of the armed services. On Sunday, December 7, 1941, as the map shows (see page 291), the Japanese struck both the fleet in harbor and the air bases. The attack totally surprised everyone in Hawaii. In many cases, only skeleton crews manned the ships and ammunition for antiaircraft guns was locked away. That did not need to have happened. Someone made a very great mistake that affected the entire war in the Pacific. The failures were there, but not the ones most people expect.