(11/20) Farther Afield (10 page)

Read (11/20) Farther Afield Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Pastoral Fiction, #Crete (Greece), #Country Life - England, #General, #Literary, #Country Life, #England, #Fiction, #Villages - England

She looked at me, and smiled.

'I really shouldn't be worrying you with my problems, but you have such a sympathetic face, you know.'

This is not the first time I have been told this. I cannot help feeling that my face works independently of my inner thoughts. It certainly seems to make me the repository of all kinds of unsolicited confidences, as I know to my cost.

'I'm quite sure,' she continued, screwing on the stopper of the lotion bottle, 'that my daughters wouldn't be putting up with this situation. For one thing, of course, they could be financially independent, a thing I've never been.'

'Even if you were,' I said cautiously, 'you wouldn't part from your husband surely?'

'No, I suppose not.' She sounded doubtful. 'There's been no choice, of course. I wasn't brought up to do a job of any kind, and I married fairly young. Now I suppose I am virtually unemployable. I must stay with John, or starve.'

She laughed, rather tremulously, and hastened to skate away from this thin ice. She spoke firmly.

'No, of course, I wouldn't leave him. We really are devoted to each other, and he is a wonderful husband. It's just this terrible problem...'

Her voice trailed away. Sighing, she lay down again, and stretched herself, enjoying the warm air, heavy with the scent of orange blossom.

Far away a gull cried, and water slapped rhythmically against a wooden boat moored by the little stone jetty. It seemed sad to me that such an earthly paradise should be spoilt for this poor woman by the cloud of worries which surrounded her.

One's first thought was how selfish her husband was to insist on disrupting her happy domesticity.

On the other hand he had served his country well presumably, had been uprooted time and time again in the course of his duties, and surely he was entitled to spend his retirement in the place he had always loved.

A pity they were married, I thought idly. Separately, they could have been so happy – she in Surrey, he in Crete. Or would they have been? Obviously, they loved each other. She would not be suffering so if she were not concerned for his happiness.

Ah well! There was a lot to be said for being single. One might miss a great deal, but at least one's fife was singularly uncomplicated.

Side by side, spinster and spouse, we both slipped into slumber, as the sun climbed the Cretan sky.

9 At Knossos

T

HE

night before our trip to Knossos we had a thunderstorm, frightening in its intensity.

Normally, I enjoy a thunderstorm at night when the black sky is cracked with silver shafts, and sheet lightning illumines the downs with an eerie flickering. Nature at her most dramatic can be very exhilarating, but a Mediterranean storm was much more alarming, I discovered, than the Fairacre variety.

The sea had become turbulent by the time we undressed for bed. The usual gentle lapping sound was transmuted to noisy crashes. Our little stone house, so solidly built, seemed to shudder in the onslaught from the sea.

But soon the noise of the waves was lost in the din of the storm. Thunder rumbled and cracked like a whip overhead. The lightning seemed continuous, turning the bay into a grotesquely coloured stage-set, against which the moored boats jostled and dipped like drunken men trying to stay upright.

The rain came down like rods. Everything glistened, roofs, walls, trees and flowers. And everywhere there was the sound of running water. It poured from gutters, rushed down slopes, turning the brick paths to rivers, and washing the carefully garnered soil down to the sea below.

'You can't wonder,' shouted Amy, above the din, from her bed, 'that the Greeks made sacrifices to propitiate the gods when they thought they were responsible for all this racket. I wouldn't mind pouring out a libation myself, to stop the noise.'

'No oil or wine available,' I shouted back, 'unless you care for a saucerful of my suntan oil.'

'We may as well put on the light and read,' said Amy, sitting up. 'Sleep's impossible.'

Propped against our pillows we studied our books. At least, Amy did.

She was zealously preparing for tomorrow's trip by reading a guide to Knossos. Amy's powers of concentration far outstrip my own, and despite the ferocity of the storm outside, she was soon deeply engrossed.

Less dedicated, I turned the pages of one of the magazines we had brought with us, and wondered how Fairacre would react if, salary allowing, I appeared in some of the autumn outfits displayed. What about this rust-coloured woollen two-piece trimmed with red fox? Just the thing for writing on the blackboard. Or this elegant pearl-grey frock banded with chinchilla? The plasticine would settle in that beautifully.

'Do you imagine anyone ever buys these things?' I asked, yawning. 'Or do they all go to Marks and Spencer, and their local outfitter's as we do?'

Amy looked vaguely in my direction. One could see her mind gradually returning from 2000 B.C. to the present time.

'Of course someone wears them,' she replied. 'I've even had some myself when James has been feeling extra generous.'

She drew in her breath sharply. She was once again firmly in the present with all its hurts and its hopes. I cursed myself for disturbing her reading and its temporary comfort.

'Listen,' I said, 'the storm is going away.'

It was true. The rain had become a mere pattering. The thunder was a distant rumbling, the spouting of gutters diminished to a trickle.

Amy smiled and closed her book.

'That

silly

man,' she said lovingly. 'I wonder what he's doing?'

She slid down under the bedclothes and was asleep in three minutes, leaving me to marvel at the inconsistency of women.

The morning was brilliant. Everything glittered in its freshness after the storm, and the sea air was more than usually exhilarating.

We piled our belongings into the hired mini which was to carry us to Knossos, and a score of other places, during the rest of our stay. It was the cheapest vehicle we could hire, and privately I thought the sum asked was outrageous, but Amy did not turn a hair on being told the terms, and once again I was deeply conscious of her generosity to me.

'Let's lunch in Heraklion,' said Amy, 'and have a look at the museum first. Most of the things are of the Minoan period. I must have another look at the ivory acrobat, and spend more time looking at the jewellery which is simply lovely. Last time, we spent far too long gazing at frescoes, and to my mind, it's the small things which are so fascinating.'

Her enthusiasm was catching, and we drove westward towards Crete's capital in high spirits. The mini coped well with the rough surfaces and the steep gradients, and I felt considerably safer with Amy at the wheel than I had with our first coach driver.

Heraklion teemed with traffic, but Amy found a car park, with her usual competence, not far from the museum, so that all was well.

It was a wonderful building, with the exhibits well arranged, and everything bathed in that pellucid light which blesses the Greek islands. Amy and I started our tour together, but gradually drifted apart, enjoying the exquisite workmanship of almost four thousand years ago, at our own pace. I left her studying the jewellery while I went upstairs.

I could see why she and James had spent so long admiring the frescoes on their earlier visit. There was such pride and gaiety in the processions of men and women on the walls. Sport was depicted everywhere, vaulting, leaping, running, wrestling; and the famous bulls of Crete were shown in all their powerful splendour by the Minoan artists.

We spent two hours there, dazed and awed, by so much magnificence.

'What we need,' said Amy, when we met again, 'is two or three months in this place.'

'But first of all, lunch,' I said.

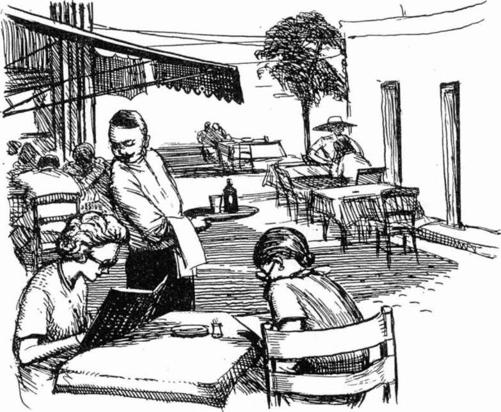

We crossed the road to some shops and cafes which seemed to have tables set out on the pavement under shady awnings. We were met by three or four garrulous proprietors, each rubbing and clapping his hands, pointing out the superior quality of his own establishment, and the extreme pleasure which he would have in receiving our custom. The noise was deafening, and the constant stream of traffic made it worse.

We were practically tugged into one cafe and settled meekly at the paper-covered table. A large dark hand brushed the remains of someone else's lunch to the ground, and a menu was thrust before us.

'All sorts of salads,' observed Amy, studying it closely, 'or something called "Pork's Livers Roasted" and another one named "Chick's Rice Fried". Unless you fancy "Heart's Beefs Noodled".'

I said I would settle for shrimp salad. We had soon discovered that the shrimps of Crete are as succulent as prawns, and much the same size. We were fast becoming shrimp addicts.

'Me too,' said Amy, giving our order to the beaming proprietor.

An American couple were deposited suddenly in the two empty chairs opposite us. They looked apologetic, as their captor rushed away to rescue the menu.

'I hope you two ladies don't object to us being thrust upon you,' said the man earnestly. 'We didn't intend to have lunch here, but were kinda captured.'

We said we had been too.

'One comfort,' said Amy, 'the food looks very good.'

'I'm sure glad to hear that,' said the man. 'I can eat most anything, but Mrs Judd here has a highly sensitive stomach, and is a sufferer from gas. Ain't that so, Mother?' he said, bending solicitously towards his wife, who was studying our fellow diners' plates with the deepest suspicion.

Mother, who must have weighed fourteen stone and had a mouth like Mrs Pringle's, with the corners turned down, was understood to say she couldn't relish anything in this joint, and how about pushing on?

Her husband consulted a large square watch on a hairy wrist, and surmised time was on the short side if they wanted to take in Knossos, and get back again for shopping, before meeting the Hyams for a drink at 6 o'clock. He guessed this place was as good as the next, and at least they were at the table, no lining up like that goddam place they went to yesterday, so why not make the best of it?

Mother pouted.

Of course, said her husband swiftly, if Mother was real set on going elsewhere, why, that was fine by him! Just whatever Mother wanted.

At that moment the menu arrived.

'Beefs very good. Porks very Good. Chicks very good. Salads very good,' chanted the waiter, his eyes darting this way and that in quest of yet more clients.

'What you two girls having?' asked Mother grumpily.

'Shrimp salad,' we chorused.

'That'll do me, Abe,' she said, 'the tomaytoes are certainly fine in this country. You got tomaytoes?' she added anxiously.

'Plenty tomaytoes,' nodded the waiter. 'Tomaytoes very good. You like?'

'I'll have the same,' said Abe.

The waiter vanished. Abe patted Mother's hand, and beamed upon her.

'You certainly know what you like,' he said proudly. If she had suddenly explained Einstein's theory he could not have been more respectful.

Our shrimp salads arrived, and Abe and Mother studied them as we ate. They were delicious, and soon a mound of heads and tails grew at the side of our enormous white plates.

A thin white cat weaved her way from the shop through the legs of the chairs, and sat close to us.

With thoughts of my incarcerated Tibby, I handed down a few shrimp heads. There was a rapid crunching, and the pavement was clear again. I repeated the process. So did the cat.

'Like a miniature Hoover,' commented Amy.

'Starving, poor thing,' said Mother. 'Or got some wasting disease maybe.'

'I haven't seen any animals looking hungry in Crete,' I said, coming to the defence of our hosts. 'Cats in hot climates often look thin to our eyes.'

'I was raised where cats were kept in their place,' said Mother. 'If us kids had fed our animals at the table, we'd have caught the rough side of our Pa's tongue.'

I forbore to comment.

'You ladies aiming at going to Knossos?' asked Abe, changing the subject with aplomb.

We said we were.

'You done the museum?'

We said we had.

'Some beautiful things there,' said Mother, 'but I didn't care for the ladies in the wall-paintings. Shocking to think they went topless like any disgusting modern girl. I sure was thankful our Pastor wasn't present. What did you think, Abe?'

Abe looked uncomfortable.

'Well, I thought they were proper handsome. Fine upstanding girls they looked to me.'

Mother gave him a stern look.

'After all,' said Abe pleadingly, 'it was a long time back. Maybe they didn't know any better.'

At that moment, their plates arrived, and we asked for our bill and paid it.

'See you at Knossos!' shouted Abe, as we said our farewells and walked away from the table.

'Do you take that as a threat or a promise?' asked Amy, when we were safely out of earshot.

As luck would have it, we did not come across our friends at Knossos, but Amy commented on them as we parked the car at the gates at the site of the ruined palace.

'I wonder how many English wives would be pandered to as Mother is,' she mused.