(11/20) Farther Afield (20 page)

Read (11/20) Farther Afield Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Pastoral Fiction, #Crete (Greece), #Country Life - England, #General, #Literary, #Country Life, #England, #Fiction, #Villages - England

As usual, she was looking as if she had come out of a bandbox, elegant in dark green with shoes to match. I became conscious of my shabby camel car coat, heavily marked down the right sleeve with black oil from the lock of the car door, and my scuffed car shoes.

'Nearly finished?' she asked.

'Just about. A pound of sprouts, and I'm done.'

'Let's have a spot of lunch together at "The Bull",' suggested Amy. 'They do some very good toasted sandwiches in the bar, and I'm famished.'

'So am I. An hour's shopping in Caxley finishes me. Partly, I think, it's the smug pleasure with which half the assistants tell you they haven't got what you want.'

'And that it's no good ordering it,' added Amy. 'I know. I've been suffering that way myself this morning.'

I bought my sprouts, and we entered 'The Bull'. A bright fire was welcoming and we sank gratefully into the leather armchairs to drink our sherry. We were the only people in the bar at that moment, for we were early. Within a short time, the place would be crowded.

'Vanessa's back at work,' said Amy.

'Did Gerard take her to Scotland?'

'Oh no, he's back in London in his little flat, putting the final touches to the book, I gather. A very personable young man picked her up. I never did catch his name. Could it have been Torquil?'

'Sounds likely. I take it he was a Scot?'

'They're

all

Scots at the moment, which makes me anxious about Gerard. He really should be a little more alert if he wants to capture Vanessa.'

'Perhaps he doesn't.'

Amy's mouth took on a determined line.

'I'm quite sure

she

is fond of him. She talks of him such a lot, and is always asking his advice. You know, she really

respects

Gerard. Such a good basis for a marriage where there is a difference in age.'

'Well, there's nothing you can do about it,' I pointed out. 'Have another sherry?'

I went to get our glasses refilled. Amy was looking thoughtful as I replaced them on the table by the sandwiches.

'James was down during the week,' she said. 'He looks worried to death. I don't know whether the girl is wavering and he is having to increase his efforts, or whether he senses that I'm wavering, but something's going to give before long. And I've a horrible feeling it's going to be me. It's an impossible situation for us all. What's more, I keep getting tactful expressions of sympathy from people in the village, and I'm not sure that that isn't harder to bear than James's indiscretions.'

I remembered Miss Clare.

'You can't keep any secrets in a village,' I said. 'You know that anyway. Don't let that add to your worries.'

'But how do people find out? I've not said a word to a soul. Even Mrs Bennet, our daily, knows nothing.'

'You'd be surprised! A lot of it's guesswork, plus putting two and two together and making five. Bush telegraph is one of the strongest factors in village life, and works for good as well as ill. Look how people rallied when I broke my arm!'

'Which reminds me,' said Amy, looking at her watch. 'I must get back to pack up the laundry. Mrs Bennet hasn't been for the last two days. She's down with this wretched measles. Caught it from her grandchild.'

'There's a lot about. Three more cases last week in the infants' room.'

'There's talk of closing Bent School,' Amy told me. 'Actually, they rang up last week to see if I could do some supply work there, but I felt I just couldn't with James coming down, and so much hanging over me. They're two staff short, and no end of children away.'

'Have you had it?'

'What, measles? Yes, luckily, at the age of six or seven, and all I can remember is a bowl of oranges permanently by the bedside, and the counterpane covered with copies of

Rainbow

and

Tiger Tim's Annual.

'

We collected our shopping and made for the door, much fortified by 'The Bull's' hospitality.

'I wonder if I've got the stamina to go looking for a new winter coat,' I mused aloud.

Amy eyed my dirty sleeve.

'You certainly look as though you need one,' she commented.

'The thing is, should it be navy blue or brown? In a weak moment last year I bought a navy blue skirt and shoes, and I ought to make up my mind if I'm to continue with navy blue, which means a new handbag as well, or play safe with something brown which will go with everything else.'

Amy shook her head sadly.

"Well, I can't spare the time to come with you, I'm afraid. What problems you set yourself! And you know why?'

I shook my head in turn.

'

No method!

' said Amy severely, waving goodbye.

She's right, I thought, watching her trim figure vanishing down the street.

I decided that I could not face such a problem at the moment, collected my car and drove thankfully along the road to Fairacre.

The conker season was now in full swing. Rows of shiny beauties, carefully threaded on strings, lined the ancient desk at the side of the room, and as soon as playtime came, they were snatched up and their owners rushed outside to do battle.

There were one or two casualties understandably. Small boys, swinging heavy strings of conkers, and especially when faced with defeat, are apt to let fly at an opponent. One or two bruises needed treatment, usually to the accompaniment of heated comment.

'He done it a-purpose, miss.'

'No, I never then.'

'I saw him, miss. Oppin mad, he was, miss.'

'Never! I saw him too, miss. They was jus' playin' quiet-like. It were an accident.'

'Cor! Look who's talking! What about yesterday, eh? You was takin' swipes at all us lot, with your mingy conkers.'

'Whose mingy conkers? They beat the daylights out of yourn anyway!'

Luckily, the conker season is a relatively short one, and the blood cools as the weather does.

Out in the fields the tractors were ploughing and drilling. We could hear the rooks, dozens of them, cawing as they followed the plough, flapping down to grab the insects turned up in the rich chocolate-brown furrows.

The hedges were thinning fast, and a carpet of rustling leaves covered the school lane. Scarlet rose hips and crimson hawthorn berries splashed the hedgerows with bright colour, and garlands of bryony, studded with berries of coral, jade and gold, wreathed the hedges like jewelled necklaces.

The children brought hazel nuts and walnuts to school, cracking them with their teeth, and as bright-eyed and intent as squirrels as they examined their treasures. Their fingers were stained brown with the green husks from the walnuts, and purple with the juice from late blackberries. Plums and apples from cottage gardens joined the biscuits on the side table ready for playtime refreshment. Autumn is the time of plenty, of stocking up for the lean days ahead, and Fairacre children take full advantage of nature's bounty.

So do the adults. We were all busy making plum jam and apple jelly, and keeping a sharp eye on the wild crab apples which would not be ready until later. There are several of these trees among the copses and hedges of Fairacre, and most years there is plenty of fruit for everyone. One year, however, soon after I arrived in Fairacre, there was a particularly poor crop of these lovely little apples. A newcomer to the village, one of the 'atomic wives', living in the cottage now inhabited by young Derek and his parents, was rash enough to pick the lot, much to the fury of the other good wives of Fairacre. I remember, in my innocence, attempting to be placatory, suggesting that ignorance, rather than greed, had prompted her wholesale appropriation.

'We'll learn her!' had been the vengeful cry. And they did. Perhaps it was as well that her husband was posted elsewhere after this unfortunate incident. I can't think that she really enjoyed her crab apple jelly.

There is a very neighbourly feeling about picking these wild fruits, and very few would strip a hedge of nuts or blackberries. Leaving some for the next comer is usual. It is as though the generosity of nature communicates itself to those blessed by it, and many a time I have heard the children, and their parents, recommending this hedge or that tree as the best place to try harvesting.

One of the group of elms at the corner of the playground was considered unsafe and had to come down. The children were allowed to watch the operation at a respectful distance. The two men had the small branches off, the trunk sawn through and the giant toppled, all within the hour.

It fell with a dreadful cracking sound, and thumped into Mr Roberts' field beyond. The children raised a great shout of triumph, but one of the infants grew tearful and said:

'I don't like it falling down.'

'Neither do I,' I said. We seemed to be the only two who felt saddened at the sight. Everyone else rejoiced, but I cannot see a tree felled, particularly a majestic one such as this was, without a shock of horror at the swift killing of something which has taken a hundred years or more to grow, and has given shelter and beauty to the other lives about it.

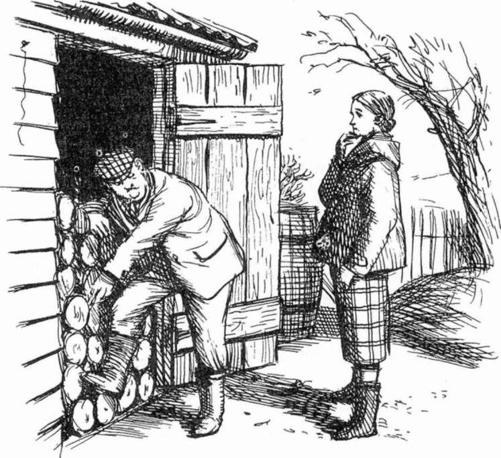

However, I was not too shattered to be grateful for some of its logs which Mr Willet procured for me. I helped him to stack them in my wood shed one afternoon after school.

The sky was that particularly intense blue which occasionally occurs in October. Across the fields, in the clear air, the trees glowed in their russet colours. It was invigorating handling the rough-barked wood, knowing that the winter's fires would be made splendid with its burning.

But it was cold too. Mr Willet, stacking the final few, blew out his moustache.

'Have a frost tonight, you'll see. Got your dahlias up?'

I had not. Mr Willet evinced no surprise.

'Shall I do 'em for you now?' he offered.

'No need. I've kept you long enough. It's time you were home.'

'That's all right. Alice has gone gadding into Caxley to a temperance meeting.'

Gadding seemed hardly the word to use under the circumstances, I felt.

'Come and have a cup of tea with me then,' I said. We stood back to admire the stack of logs before making for the kitchen.

'That baby of Mrs Coggs has got the measles, they say,' said Mr Willet, stirring his tea. 'Them others away from school?'

'Not today. I'd better look into it. Two more infants are down with it, but we're not as badly off as Bent.'

I told him what Amy had said about the possibility of the school there having to close.

'And how is your friend?' enquired Mr Willet. 'I did hear,' he added delicately, 'that she was in a bit of trouble.'

Here we were again, I thought. I had no desire to snub dear old Mr Willet, but equally I had no wish to betray Amy's confidences.

'Aren't we all in a bit of trouble, one way or the other?' I parried.

'That's true,' agreed Mr Willet. 'But you single ones don't have the same trouble as us married folk. Only got yourself to consider, you see. Any mistakes you make don't rebound on the other like. Take them dahlias.'

'What about them?'

I was relieved that we seemed to have skated away from the thin ice of Amy's affairs.

'Well, if my Alice'd forgot them dahlias, I should have cut up a bit rough, seeing what they cost. But you, not having no husband, gets off scot free.'

'Not entirely. I shall have to pay for any new ones.'

'Yes, but that's your affair. There ain't no

upsets,

if you see what I mean. No bad feelings. You can afford to be slap-dash and casual-like. Who's to worry?'

I laughed.

'You sound like Mrs Pringle! Am I really slap-dash and casual, Mr Willet?'

'Lor, bless you,' said Mr Willet, rising to go, 'you're the most happy-go-lucky flibbertigibbet I've ever met in all me born days! Many thanks for the tea, Miss Read. See you bright and early!'

And off he went, chuckling behind his stained moustache, leaving me dumb-founded – and with all the washing-up.

I had time to savour Mr Willet's opinion of me as I sat knitting by the fire that evening. I was amused by his matter-of-fact acceptance of my shortcomings. His remarks about the drawbacks of matrimony I also knew to be true. Any unsettled feelings I had suffered during the holidays, had quite vanished, and I realised that I was back in my usual mood of thinking myself lucky to be single.

For some unknown reason I had a sudden craving for a pancake for my supper. I had not cooked one for years, and thoroughly enjoyed beating the batter, and cutting a lemon ready for my feast. I even tossed the pancake successfully, which added to my pleasure.

If I were having to provide for a husband, I thought, tucking into my creation, a pancake would hardly be the fare to offer as a complete meal. No doubt there would be 'upsets', as Mr Willet put it. Yes, there was certainly something to be said for the simple single life. I was well content.

The fire burnt brightly. Tibby purred on the rug. At ten o'clock I stepped outside the front door before locking up. There was a touch of frost in the air, as Mr Willet had forecast, and the stars glittered above the elm trees. Somewhere in the village a dog yelped, and near at hand there was a rustling among the dry leaves as some small nocturnal animal set out upon its foraging.