1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (37 page)

Read 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War Online

Authors: Benny Morris

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

6.88Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Political and military developments in the last days of 1947 and early 1948 tended to cloud Arab judgment. The UN partition resolution threw all the leaders into a frenzy. But no major change of policy was immediately required since Jewish statehood was not yet a tangible reality; perhaps the Palestinian Arabs would yet thwart it. The battles of April 1948 and the imminent prospect of British evacuation and Jewish statehood changed all that. During April and early May there were nonstop deliberations, mainly in Cairo, Damascus, and Amman, among the Arab kings, presidents and prime ministers, and military commanders. Alec Kirkbride, the all-knowing British minister in Amman, described those last days before the invasion as "bedlam, the like of which I have never yet experienced. I cannot attempt to recount or record the numerous conversations which I have [had] with Arab leaders going over the same ground again and again advocating caution ... only to have all the work undone by desperate appeals for help from somewhere in Palestine or by the arrival of a new batch of refugees with new rumors."

The consensus favoring invasion began to crystallize at the meeting in Cairo, starting io April, of the Arab League Political Committee. In the air was the ever-worsening news from Palestine- Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini's death, Deir Yassin, and the failure of the Arab Liberation Army at Mishmar Ha'emek-and the growing pleas by Palestine Arab notables to the Arab governments to intervene.9 Safwat said that Palestine was lost unless the armies invaded; Jordan indicated that the Legion would go in when the British left (though not before).'() Syria and Lebanon, seemingly chafing at the bit, pressed Egypt to commit its army. But Prime Minister Mahmoud Nuqrashi argued, as before, that Egypt could not participate because the British army, in its bases along the Suez Canal, sat astride its lines of supply to Palestine; who knew what perfidious Albion might do?ii As late as 26 April Foreign Minister Ahmed Muhammad Khashaba was saying that although Egypt could not and would not prevent "volunteers" from joining the fight, it "did not intend, and would not, send regular forces into Palestine."'2

Yet the momentum of Jewish victories, Palestine Arab defeats, and the minatory rumblings of the Arab street proved inexorable. Public opinion was "all in favor of the war, and considered anyone who refused to fight as a traitor."'-3 As Muhsin al-Barazi, Syria's foreign minister, put it in April: "[The] public's desire for war is irresistible."14 By May, Syrian leaders were hysterical; public opinion, they said, was "very excited," and there was talk-at least for the benefit of Western diplomatic ears-that "the whole country might go Communist and ... our [that is, Britain's] friends would be swept away. "15 The same considerations applied in Baghdad, where the leaders looked both downward, at a turbulent politically involved middle class and an excitable "street," and sideways, at fellow Arab leaders; a failure of militancy would enhance the position of the anti-Hashemite bloc (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Syria) in inter-Arab jockeying and rile the masses to the point of dangerous disturbances or worse. 16 None could ignore the Palestinian Arab tales of massacre and exodus. Nor could the Arab leaders, especially Egypt's, remain indifferent to the pressure of the Muslim religious establishment's call for "the liberation of Palestine [as] a religious duty for all Moslems without exception, great and small. The Islamic and Arab Governments should without delay take effective and radical measures, military or otherwise," pronounced the `ulema of Al-Azhar University, a major religious authority, on 26 April.' 7 Both King Farouk and Khashaba repeatedly stressed that, for "the whole Arab world," the struggle was religious. "It was for them a matter of Jewish religion against their own religion" ;18 the Arab masses, said Farouk, were gripped by "widespread religious fervour ... and men of the people were keen to enter the fray-as the shortest road to Heaven." 19

The decision to invade was finally taken on 29-3o April, at the simultaneous meetings of the Arab heads of state in Amman and the military chiefs of staff in Zarka. Egypt still held back. But the die was cast. And on ii-12 May Egypt would also commit itself to invasion. Yet the pan-Arab decision papered over a basic lack of preparation and deep rifts between the states regarding the political and military goals and strategy, the unity of command, and political-military coordination.

For all their bluster from Bludan through Cairo, the Arab leaders-except Jordan's-did almost nothing to prepare their armies for war. They may have prodded one another into ever greater fervor, and they most certainly whipped up their "streets" into hysteria over their suffering brothers in Palestine. But in concrete military terms, they failed to prepare.

Britain and France had established the Arab armies to help maintain their imperial grip, to prop up unpopular client regimes, and to maintain internal order; the armies had never been intended or structured for external warfare. Only in 1945 -1946, against the backdrop of the emergent Cold War, did the British begin to prepare or help in the conversion of the Egyptian, Iraqi, and Jordanian armies into modern fighting forces, capable of serving as auxiliaries in a fight with the Soviet Union. But lack of funds, incompetence, poverty, and suspicion of Britain's intentions frustrated the conversion in Egypt and Iraq. Similar problems discouraged the development, under French tutelage, of the newborn Syrian and Lebanese armies. Only the Jordanian army, and this very late in the day, began a real upgrade as May 1948 approached.20

Most of the Arab generals seem to have assumed that war would never come, or that their country would not participate, or that it would be a walkover. None of their armies had ever fought a war (except part of the Arab Legion, which had assisted the British army's conquest of Iraq and Syria in May-June 1941), and none really knew what war would entail. In the days before the invasion, the military and political leaders, gripped by a war psychosis, oscillated between complete contempt for the Jews and fatalism. Without doubt, "cultural misperceptions and racist attitudes toward Jews in general blinded and entrapped Arabs," as one historian has put it.21

Gamal Abdel Nasser, who fought in Palestine, later summarized the Egyptian preparations and intentions: "There was no concentration of forces, no accumulation of ammunition and equipment. There was no reconnaissance, no intelligence, no plans.... [It was to be a `political war.'] There was to be advance without victory and retreat without defeat. "22 In the Egyptian high command, there was an absence of realism and clear-headedness.

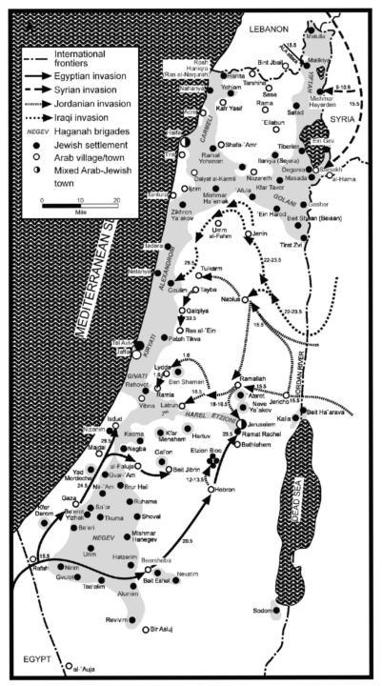

The Pan-Arab Invasion of Palestine/Israel, May-June 1948

"A parade without any risks" and Tel Aviv "in two weeks," was how the Egyptian army chiefs in May presented the coming adventure to their political bosses23-even though, just weeks before, they had spoken firmly against intervention, arguing lack of training, arms, and ammunition. In January 1948, the British, who were helping reorganize the army, assessed: "The Egyptian Army hardly warrants consideration as a serious invading force." Two months later the Egyptian war ministry offered the same evaluation.24 "We shall never even contemplate entering an official war. We are not mad," the Egyptian defense minister, General Muhammad Haidar, told one journalist before the invasion.25 Yet several days later, he reportedly said: "The Egyptian military is capable on its own of occupying Tel Aviv ... in fifteen days, without assistance."26 But the commander-elect of the Egyptian expeditionary force, General Ahmed `Ali al-Muwawi, told Haidar that his troops were not ready. Al-Muwawi's deputy, Colonel Mohammed Neguib, also spoke bluntly about Egyptian unpreparedness-"Why court disaster?"27 But Prime Minister Nuqrashi believed, or, as 15 May approached, pretended to believe, that "the whole affair would be a military picnic."28 He reassured the officers that "there was no need for undue alarm. There would be very little fighting for the United Nations would intervene." He spoke of a "political demonstration" rather than of real battles.29 Nuqrashi, against his better judgment, seems simply to have bowed to King Farouk's will. Farouk was driven by a hatred of Zionism, fear of the "street," a quest for glory, and a desire to stymie or at least counterbalance expected Hashemite gains in Palestine.

Only one prominent Egyptian raised his voice in protest. Ahmed Sidqi Pasha, a respected former prime minister, who in the past had (at least privately) supported partition,30 called out in the secret debate in the Egyptian senate on 11-12 May, when Nuqrashi requested a vote for war: "Is the army ready?"-31 But nobody listened. The "aye" votes were unanimous. Sidqi alone walked out of the chamber without voting32-and, a few days later, in a newspaper interview, courageously cast doubt on "whether Egypt was fully prepared to face a situation created . . . `by misplaced enthusiasm and a hastily improvised policy.' "33

In the wider Arab world, Sidqi was not alone. King Abdullah had always acknowledged Arab (as distinct from Jordanian) weakness, and his son, Prince Talal, openly predicted defeat.34 At the last moment, several leaders, including King Ibn Saud and Azzam Pasha-to avert catastrophe-secretly appealed to the British to soldier on in Palestine for at least another year.-3s Egypt's foreign minister, Khashaba, had already done so. He "wished they would remain, and suggested that it was their duty to do so."36

Of course, the pessimists were right. The Arab military had done no proper planning or intelligence work (as one Arab participant-chronicler of the war put it, "the Arab intelligence services displayed complete contempt in assessing the enemy's strength"),37 armaments and ammunition were in short supply, and logistics were inadequate, especially in those armiesEgypt's and Iraq's-that had to travel hundreds of miles before reaching the battlefields. Neguib, the deputy commander of the Egyptian expeditionary force, later recalled that he had had personally to hire twenty-one trucks from Palestinian Arabs to haul his troops from Rafah to Gaza.3S And the Egyptians invaded without sufficient ammunition, spare parts, or food stocks, and with defective weapons. (Indeed, during the Revolution of July 1952, Neguib, in his letter to Farouk demanding the king's resignation, specifically charged the king with responsibility for "the traffic in defective arms ammunition" in 1948.)39 Officers and soldiers alike were unprepared for what faced them-a tenacious, highly motivated enemy, well dug-in and fighting on home turf, with short, internal lines of communication and already superior to them in organization and numbers; eventually, the Israelis would also, at least in some categories of weaponry, be better equipped.

But realistic military considerations and evaluations had little effect on the political decision-making. The invasion was decided on despite the Arab regimes' overarching political priorities: for Egypt and Iraq, the eviction of the "imperialist" (British) presence; for most of the governments, the maintenance of power in the face of potentially lethal internal social and political unrest. Only for Jordan's Abdullah was the invasion-viewed as a means to expand his kingdom-an immediate political priority.

Around the Arab world, flights of fancy and boastful militant rhetoric were given their head. By the start of May, the Arab leaders, including Abdullah, found that they were trapped and could do no other-whatever the state of their armies. "The politicians, the demagogues, the Press and the mob were in charge-not the soldiers. Warnings went unheeded. Doubters were denounced as traitors," Glubb recalled.'() In most Arab states the opposition parties took a vociferous, pro-war position, forcing the pace for the generally more sober incumbents. From late November 1947 until mid-May 1948 the streets of Cairo, Alexandria, Beirut, Damascus, and Baghdad were awash with noisy "pro-intervention" demonstrations, organized at least in part by the governments themselves. The press, too, both reflecting and fashioning opinion, chimed in with belligerent rhetoric, growing in stridency as i5 May approached. The leaders found themselves ensnared in their own rhetoric and that of their peers. By IS May, not to go to war appeared, for most, more dangerous than actually taking the plunge. Azzam Pasha put it in a nutshell: "[The Arab] leaders, including himself, would probably be assassinated if they did nothing."41

What was the goal of the planned invasion? Arab spokesmen indulged in a variety of definitions. A week before the armies marched, `Azzam told Kirkbride: "It does not matter how many [ Jews] there are. We will sweep them into the sea."42 Syrian president Shukri al-Quwwatli spoke of the Crusades: "Overcoming the Crusaders took a long time, but the result was victory. There is no doubt that history is repeating itself."4" Ahmed Shukeiry, one of Haj Amin al-Husseini's aides (and, later, the founding chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization), simply described the aim as "the elimination of the Jewish state."44

But officially and publicly, the Arab states were more circumspect and positive. Most described the aim of the invasion as "saving" the Palestinian Arabs. Typical was the Egyptian government invasion-day announcement: it had ordered its army into Palestine "to re-establish security and order and put an end to the massacres perpetrated by Zionist terrorist bands against Arabs and humanity."45 Less carefully, al-Quwwatli told his people: "Our army has entered Palestine with the rest of the Arab states' [armies] to protect our brothers and their rights and to restore order. We shall restore the country to its owners, we shall win and we shall eradicate Zionism."46

Other books

The Walker in Shadows by Barbara Michaels

Mail Order Menage by Abel, Leota M

Still Standing: The Savage Years by O'Grady, Paul

Deadly Deeds by Kathryn Patterson

La chica del tiempo by Isabel Wolff

The Island by Victoria Hislop

The South Lawn Plot by Ray O'Hanlon

The Reluctant Duchess by Winchester, Catherine

Trouble by Kate Christensen

Glitter Baby by Susan Elizabeth Phillips