1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (6 page)

Read 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War Online

Authors: Benny Morris

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

12.2Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

From 1920, the Yishuv had a "national" militia, the Haganah, which in mid-1948 became the army of the new state, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). To run its institutions, the Yishuv efficiently taxed itself. By contrast, the Arabs relied for their institutions, such as the Supreme Muslim Council, and their services on British government funding.

Starting in April 1936, armed Arab bands, based in the villages and the urban casbahs, began to attack Jewish traffic and passersby. At the same time, the Palestinians reorganized politically, setting up National Committees (NCs) in each town and the Arab Higher Committee to oversee their struggle nationally. Both the AHC and the NCs initially represented the various political factions. The AHC declared an open-ended general strike and demanded British withdrawal and Palestinian independence under Arab rule. At the least, the rebels hoped to bludgeon the British into curbing the growth of the Zionist enterprise and Jewish immigration.

The revolt enjoyed popular support throughout the Arab Middle East. Even before its outbreak, the Arab world had been smoldering with the idea of a jihad (holy war) against the Yishuv. The speaker of the Iraqi parliament, Said al-Haj Thabit, on a visit to Palestine in March 1936, repeatedly called for such a jihad.26

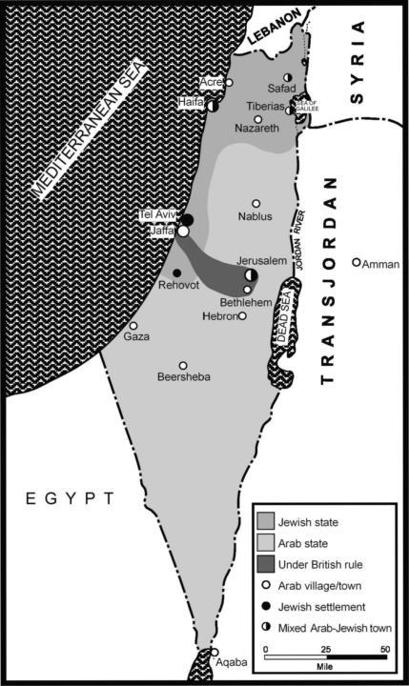

But the revolt was somewhat lackadaisical: initially, few Palestinians actually participated in hostilities, and they were disorganized and poorly led and equipped. By October they had managed to kill only twenty-eight Britons and eighty Jews (at a cost of some two hundred Arab dead). The British and the Yishuv reacted with restraint, though London began to curtail Jewish immigration. After five months of struggle, the Palestinians were exhausted and the sterling-earning citrus harvest season was kicking in. The British were happy to call it quits and covertly helped Haj Amin al-Husseini suspend the rebellion. London then dispatched to Palestine yet another committee of inquiry, this time a royal commission, headed by Lord Peel. On 7 July 1937 the commission published a 4o4-page report. It exhaustively traced the history of the conflict and present realities and concluded both that the Mandate was unworkable and that the Jews and the Arabs could not live under one political roof. The commissioners recommended partition, with the Jews getting zo percent (the Galilee and much of the Coastal Plain) on which to establish a state, and the Arabs getting more than 70 percent (Samaria, much of Judea, and the Negev), which should eventually be fused with Transjordan to create an enlarged Hashemite state under Emir 'Abdullah. Something less than io percent of the country, including Jerusalem and Bethlehem, with their holy sites, and a strip of territory connecting the capital to the Mediterranean at Jaffa, should be retained by the British. The commission further recommended that the bulk of the three hundred thousand Arabs who lived in the territory earmarked for Jewish sovereignty should be transferred, voluntarily or under compulsion, to the Arab part of Palestine or out of the country altogether. The commission "balanced" this by recommending that the ►,z5o Jews living in areas earmarked for Arab sovereignty be moved to the Jewish area-deeming the proposed transaction "an exchange of population."

The Peel Commission partition proposal, July 1937

In their testimony before the commission, the Zionist mainstream representatives had laid claim to the whole of the Land of Israel-the traditional Zionist platform. But in private conversations, Weizmann and others indicated a readiness for compromise based on partition as well as, quite probably, suggesting the "transfer" solution to the demographic problem posed by the prospective large Arab minority in the Jewish area. Zionism's leaders, from Herzl through Menahem Ussishkin and Arthur Ruppin, had periodically proposed-in private letters and diaries-transfer as the requisite solution to the "Arab problem." But transfer had never been adopted by the movement or any of the main Zionist parties (including the right-wing Revisionists) as part of a platform or official policy. Once the Peel Commission had given the idea its imprimatur, however, the floodgates were opened. Ben-Gurion, Weizmann, Shertok, and others-a virtual consensus-went on record in support of transfer at meetings of the JAE at the Twentieth Zionist Congress (in August 1937, in Zurich) and in other forums.

To be sure, these advocates realized and usually acknowledged that the idea was impractical and unrealistic-the British could not be expected to carry out transfer, and the Yishuv, even if willing, was powerless-and transfer was never adopted as official Zionist policy. Yet through the late 193os and early and mid-194os Zionist leaders continued in private to espouse the idea. For example, Weizmann in late January 1941 told Ivan Maiskii, the Soviet ambassador to London: "If half a million Arabs could be transferred, two million Jews could be put in their place.... Weizmann said that ... they would be transferring the Arabs only into Iraq and Transjordan."27 Interestingly, senior British officials and Arab leaders, including Emir `Abdullah and Nuri Said, Iraq's premier politician (the same Nuri Said who in July 1939 called for the destruction of Zionism), shared this view.2I All understood that for a partition settlement to work and last, the emergent Jewish state would have to be ridded of its large and potentially or actively hostile Arab minority. As `Abdullah's prime minister, Ibrahim Pasha Hashim, put it in 194-6: "The only just and permanent solution lay in absolute partition with an exchange of populations; to leave Jews in an Arab state or Arabs in a Jewish state would lead inevitably to further trouble between the two peoples."29 `Abdullah, according to Britain's representative in Amman, Alec Kirkbride, concurred.30

The Peel recommendations enshrined the principles of partition and a "two-state" solution as the international community's preferred path to a settlement of the conflict and were adopted by the mainstream of the Zionist movement (the minority right-wing Revisionists dissented). But the Husseini-led Palestinian leadership, and the Arab states in its wake, rejected both the explicit recommendations and the principle: all of Palestine was and must be ours, they said. They also, of course, abhorred the transfer recommendation.

Responding to the Peel proposals, which Whitehall immediately endorsed, the Husseinis renewed the rebellion in late September 1937. The Opposition, which initially approved the recommendations and then recanted, sought to extend the truce, but vilified as traitors, they were effectively cowed and silenced by a Husseini campaign of terrorism.

The second and last stage of the rebellion, lasting until late spring-summer 1939, was far bloodier than the first. The Arab rural bands renewed their attacks and were active in the towns as well. The Revisionist movement's military arm, the Irgun Zvai Leumi (IZL, the National Military Organization, or simply Irgun), which had been formed by activist breakaways from the Haganah, subjected the Arab towns to an unnerving campaign of retaliatory terrorism, with special Haganah units adding to the bloodshed through selective reprisals. More important, the British now took off the gloves. In October 1937 they outlawed the AHC and the NCs and arrested many of their members. Haj Amin al-Hussein himself fled into exile, where he remainedalternating mainly between Beirut and Cairo-until his death in 1974. After the rebellion peaked in summer 1938 (the rebels briefly occupied the Old City of Jerusalem and Beersheba) and after being temporarily freed by the Munich Agreement from the specter of war in Europe, the British went on the offensive, clamping down hard. Between October 1938 and April 1939 British units pushed into the casbahs and the rebel strongholds in the hill country and virtually annihilated the bands after coercing much of the rural population into collaboration. Dozens of houses were demolished, crops were destroyed, rebels and their accomplices were hanged, and thousands were jailed. In suppressing the rebellion, the British fenced and mined Palestine's northern borders and secured towns and crossroads around the country with reinforced concrete police and army posts, called Tegart forts (which were to figure large in the battles of 1948 and mostly exist to this day, serving as Israeli and Palestinian Authority police stations). In identifying the rebels' infrastructure, the British were assisted by the Haganah Intelligence Service, organized toward the end of the rebellion, and by newly created Opposition-aligned, anti-Hussein "peace bands," that denied the rebels entry into dozens of villages. There was no formally announced end to the rebellion, but hostilities tapered off in spring and summer 1939, With the surviving rebels fleeing to Lebanon and Syria.

Yet the rebellion, coming as it did as Britain faced a worldwide three-front war against Japan, Italy, and Germany, almost succeeded-not militarily but politically. From the September 1938 Munich crisis onward, Britain came to view its Palestine policy almost exclusively through the prism of its needs and interests in the forthcoming global struggle. Simply put, London sought to appease the Arabs to assure quiet in the Middle East, which sat astride Britain's lines of communication to southern Asia and the Far East. In May 1939 Whitehall issued a new white paper. It promised Palestine's inhabitants statehood and independence within ten years; severely curtailed Jewish immigration, limiting it to fifteen thousand entry certificates per year for five years, with all further Jewish immigration conditional on Arab approval (thus assuring an overwhelming Arab majority when independence came); and significantly limited Jewish land purchase. In sum, this amounted to a complete reversal both of the Balfour Declaration policy and its muchmodified translation, the Peel Commission recommendations: Palestine was to remain Arab, and there would be no Jewish state. The Yishuv denounced the white paper as "illegal" and "appeasement" and mounted huge protest demonstrations; the IZL initiated sporadic attacks on British installations.

The Palestinian street was overjoyed. But al-Husseini-as was the Palestinians' wont-managed to pluck defeat from the jaws of victory. Instead of welcoming the British move, which Winston Churchill denounced as a cowardly "surrender to Arab violence," al-Hussein and his colleagues rejected the white paper. They flatly demanded frill cessation of Jewish immigration, immediate British withdrawal, and immediate independence.

In the brief months before world war broke out, nothing changed. The Arab Revolt thus ended in unmitigated defeat for the Palestinians. Somewhere between three thousand and six thousand of their political and military activists had been killed, with many thousands more either driven into exile or jailed; the leadership of the Palestine Arab national movement was decimated, exiled, or jailed; and a deep chasm, characterized by blood fends, divided the society's elite families. Indeed, much of the elite was so disillusioned or frightened by what had happened that it permanently renounced political activity. The Palestinians had also suffered serious economic harm, through both the general strike and British repression. They had prematurely expended their military power against the wrong enemy and had been dealt a mortal blow in advance of the battle with the real enemy, Zionism. The damage to their war effort in 1947-1948 was incalculable.

The triangular conflict in Palestine was put on hold for the duration of World War II. The British made it clear to the Yishuv that they would not countenance renewed troubles, and the Jews took heed. They shelved the struggle against the white paper, and tens of thousands of young Jews volunteered for service in the British army. Even the IZL sent volunteers to aid British military operations. The Zionist movement closed ranks in support of the Allies in the war against the Nazis. Palestine, awash with British troops, served as a giant rear base and workshop for the Eighth Army, which engaged the Italians and Germans in North Africa.

The Palestinians, reeling from the suppression of their rebellion and largely unsympathetic to Western liberal, democratic values, grimly hoped for an Axis victory. In this, they were at one with most of the Arab world. The Palestinians, Khalil al-Sakakini, a Christian Jerusalem educator, jotted down in his diary, "rejoiced [as did `the whole Arab world'] when the British bastion at Tobruk fell [in 1941] to the Germans."31 One of the first public opinion polls in Palestine, conducted by al-Sakakini's son, Sari Sakakini, on behalf of the American consulate in Jerusalem, in February 1941 found that 88 percent of the Palestinian Arabs favored Germany and only 9 percent Britain.32 The exiled al-Husseini himself helped raise a brief anti-British revolt in Baghdad in spring 1941 and then fled to Berlin, where he served the Nazi regime for four years by broadcasting anti-British, jihadist propaganda to the Middle East and recruiting Bosnian Muslims for the Wehrmacht. He was deeply anti-Semitic. He later explained the Holocaust as owing to the Jews' sabotage of the German war effort in World War 133 and the millennia of Gentile anti-Semitism as due to the Jews' "character": "One of the most prominent facets of the Jewish character is their exaggerated conceit and selfishness, rooted in their belief that they are the chosen people of God. There is no limit to their covetousness and they prevent others from enjoying the Good.... They have no pity and are known for their hatred, rivalry and hardness, as Allah described them in the Qur'an."34

Other books

Just Good Friends by Rosalind James

The Minoan Cipher (A Matinicus “Matt” Hawkins Adventure Book 2) by Paul Kemprecos

Catering to the CEO by Chase, Samantha

Beneath the Bonfire by Nickolas Butler

The Countess' Captive (The Fairytale Keeper Book 2) by Andrea Cefalo

Love Like You've Never Been Hurt by Sj McCoy

Lord Braybrook’s Penniless Bride by Elizabeth Rolls

If You Can't Stand the Heat... (Harlequin Kiss) by Joss Wood

Prime Deliverance (Katieran Prime Series (Book Five)) by K.D. Jones

Stronger by Lani Woodland