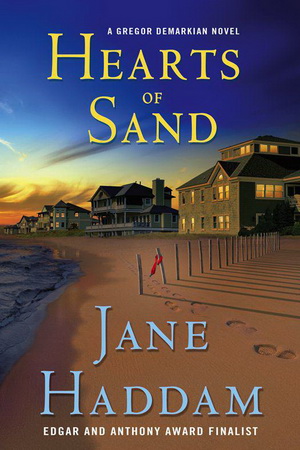

28 Hearts of Sand

Authors: Jane Haddam

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For Greg and Matt

Chaos is just order waiting to be born.

—Fernando Pessoa

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

As far as is known, ectoplasm does not perspire.

—José Saramago

1

Alwych, Connecticut, is the kind of town about which movies are made, when the movies take place in a small, self-important enclave where Pure Talent lives and pretends to run the country. The grass and shrubs and leaves are greener there, and they hang more heavily in the almost-summer heat. The long, curving arc of Beach Drive is dotted with high streetlamps that glow a particularly purified shade of white. The granite mock-Tudor wings of the Atlantic Club brush up close to the waves of Long Island Sound. Even in the center of town, where there are sidewalks, and parking meters, and a grocery store that has more sales than it should be allowed to, there is an underlying sense of self-confidence. Alwych was here before the country, and many of the people who live in it think it will be here long after the country ceases to exist. Alwych understands what other places don’t. There is virtue in being something that refuses to be moved.

Chapin Waring was standing at the landlocked end of Beach Drive. This was the part of the Drive she knew least well. When she had lived in Alwych, her family’s house was the last one on the promontory before the Atlantic Club, so that she and her sisters had been able to walk to tennis and parties across the nick in the fence at the back of the property. The house was still there. It was the first thing she had gone to see when she came in on the train this morning, as if just by seeing it, just by knowing it was there, she could change all the things that could not be changed. She had even taken one more risk in a day of taking risks and parked halfway up the drive. The reality had disappointed her a little. She had expected Manderley, ruined and majestic in a jungle of untended shrubbery. Instead, her sisters seemed to have been doing their duty. The grass was cut. The bushes were trimmed. The garden was tended. It was just a big, blank house, shingle-sided and a little weathered by the Atlantic winds. It could have belonged to anybody.

Now she looked beside her on the other front bucket seat of this rental car and tried to remember what she had and had not brought with her from “home.” It was a tricky business. The one thing she could not afford was to be seen and recognized. She rummaged through her green and white L.L. Bean canvas tote bag and came up with the gun. It looked innocent and not quite real, like a prop to be used in a murder mystery. She put it back in the bag—there was no point in having it out in the open—and took out a piece of cheese. She didn’t want it. She didn’t want anything, except to get done what she had to get done and then to get out, before her entire life blew up in her face.

She looked at her watch. It was an ordinary Timex watch. She looked at her shoes. They were wet because she’d walked them right into the ocean. Her mouth was dry, and her head hurt. Her hair was some color it had never been before. She wondered what would happen if she just walked right through the front door of the Atlantic Club and signed the register as a member. She wondered what would happen if she sat down on a bench on Main Street and just waited. Just, just, just. The word kept running around in her head, a truncated version of “justice.” If it was justice she wanted, she would have been more likely to get it if she’d stayed away.

She checked her watch again, trying to make herself see the dial. It was useless. She couldn’t concentrate. There had been a time in her life when she was afraid of nobody and nothing, but that time was not now. Now the tension was rising in her body like water in a rain gauge during a heavy storm.

Chapin shifted in her seat. She had been sitting in one position for too long. Her legs were beginning to ache. The radio station she’d been listening to kept promising lots and lots of rain for the end of the week. There was a hurricane coming north in the Atlantic, and so far it had missed all its usual landfalls. Chapin remembered her oldest sister telling them about the flood in 1954, when most of the houses on Beach Drive had had their porches washed away in the mess. There had been another storm, too, in the 1930s. That one had been so huge, entire neighborhoods were washed away, and the Atlantic Club lost its terrace and all its awnings.

I’m stalling,

Chapin thought. It had been decades since she thought about her life as a child in this place: the long summer evenings when the light had faded so gradually, it seemed to go on forever; the fall mornings when the roads were covered in leaves and the porches were full of old clothes stuffed with straw; the just-before-dawn darkness in winter when the cold was so bitter, keys froze in locks. Most of the time these days, she couldn’t remember a point when she hadn’t known the things she now knew. This was the point: herself, lying in the tall grass under the spreading maple tree at the front of the house, feeling the breeze in her hair as she let small kittens climb up her shirt and nuzzle at her neck.

Kittens,

she thought. It was as if she were about to star in an animated Disney movie.

She put her hand in the tote bag one more time, to make sure the gun was still there. Then she turned the key in the ignition and put the car into reverse. The longer she stayed here, the more likely it was that somebody would not only see her, but put two and two together. It didn’t matter that it had been thirty years. People remembered things.

She edged the car out onto Beach Drive, made a careful U-turn, and then made a right on the road that would take her around to the beach by the back way. It was eerie how deserted everything was. Like one of those ghost towns in a Stephen King novel, all the people had been turned into vampires.

She got to that part of the road where the sand started creeping in and pulled over to the side. From here, she would have to walk. She got out and took the tote bag with her, but she didn’t bother to lock the car’s four doors. Nobody ever locked their doors in Alwych, and besides, she wouldn’t be coming back.

2

Out on Beach Drive, Chapin Waring was trying to do the one last thing that had to be done before she could say she’d had a good day. It was hard, because the knife was a long-bladed kitchen one, and it was sunk halfway to the haft under her left shoulder blade. She couldn’t reach it, no matter how she twisted. Twisting made her hurt, anyway, and she was losing a lot of blood. There was blood everywhere now. It made a trail across the hardwood floors from the dining room to the hall to the living room. It was in the kitchen, where the tall French doors had been folded back to let in the air from the ocean.

In this house, everything was clean, and calm, and settled, but everything was dead as well. The chairs around the table in the breakfast nook were just far enough away from each other to look as if people had been sitting in them. The Royal Doulton china was stacked behind the glass doors of a double-fronted china cabinet, with pieces to make a service for thirty-four. The long, low hall cabinet had been dusted and polished. The two green-silk–upholstered love seats in the living room sat across the wide square coffee table from each other. The living room ceiling soared out of sight. The tall, gold-leaf–decorated mirror above the fireplace reflected everything and nothing. Chapin would not have been surprised if her mother had walked in wearing her afternoon pearls and carrying flowers cut from the greenhouse.

If it had been afternoon, it would have been easier. In the afternoon there was light. The windows here were so large, there was seldom any need for lights when the sun was up. Now it had to be almost ten o’clock, or later. The twenty-four-foot ceilings only made the rooms feel darker. The small pinpoint lights from the beach were ghost presences that illuminated nothing but themselves. The gun was still on the coffee table, where she had left it. She picked it up and turned it over and over in her hand. It had been fired recently. She could smell it.

If she sat down, she would never stand up again. She was never going to get out of this house alive. If she knew where her cell phone was, she could call 911. She didn’t know where it was, and didn’t know if she would call, in any case. Dying wasn’t the worst thing that could happen to someone. She wished she knew what it was she wanted. Dying wasn’t the worst thing, but it might be a thing she didn’t want for herself, at least not now.

She could hear the ocean. The French doors led out onto a terrace, and the terrace overlooked the sea. She moved carefully through the room, holding on to furniture when she could. She couldn’t hold on with her left hand, because that hurt her shoulder, and her arm wasn’t working right. She was dizzy. The air around her had become thick and acquired texture. Moving through it, she had to push it out of the way.

On the night of that last party, the one that took place three days before the world ended, she had worn a blue taffeta dress with blue silk flowers sewn into the neckline, the kind of dress her mother might have worn to come out at the Grosvenor in 1944. She had been so bored, she was barely able to see straight. The air had been as difficult to breathe then as it was now. On that night, everything in her future was settled and transparent. She would go off to Wellesley. She would marry somebody like Tim Brand. She would have a house on Beach Drive and drink double-strength vodka martinis every afternoon at five o’clock. Once a week in the summer, on Friday evenings just before dinner, she would attend a cocktail party where bottles and glasses and ice and drinks were trundled around the garden in a child’s red wagon.

The important thing was to be able to hold on to the gun, to hold it steadily. The gun had a kick to it. She’d fired it at least once today. She might have fired it more. She made herself turn, very carefully, so that she was looking at the mirror. She couldn’t really see herself in it. The light wasn’t good enough.

On the night that the world had ended, at three o’clock in the morning, when she still had Marty’s blood across the front of her dress, she came into this room and stood in front of this mirror and told herself it was the one thing she could count on. It would always be here. Even if her family sold the house and another family came to live here, they would not take the mirror down. Then she had thought about Marty and the car in the shelter of the trees off Wykeham Swamp Road, about the blood that went everywhere and the sticky thick clots of it still on her hands. If someone had seen her, they would have known that there had never been a day in her life when she was ever able to tell the truth.

She braced the backs of her knees against the edge of the long couch, the one that faced the fireplace and the mirror. She held the gun in her right hand and raised her right arm. She raised her left arm very slowly and rested her left hand against her right elbow.