(5/20)Over the Gate (20 page)

The idea of Lucy Colgate queening it in my little school was even more distasteful. Fancy leaving Patrick and Ernest, and Joseph, and Linda—all the adorable and maddening hustle of them, in fact—to the mercies of Lucy! It simply could not be done.

I had a sudden vision of Mrs Pringle's face. How would the two get on?

'The meeting of the dinosaurs,' I told myself, with some relish, my fury beginning to abate. 'What a battle that would be!' I could see Lucy facing Mrs Pringle over the tortoise stoves. Lucy spilling coke, and as yet ignorant of the consequences. Lucy would face many a hazard if she ever found herself in Fairacre School. Why, with any luck, I thought suddenly, the map cupboard door might burst open again and project the contents painfully upon her!

At this uncharitable flight of fancy, I began to laugh. Lucy Colgate and Amy could connive untd they were blue in the face! My mind was now made up. I advanced upon the unsullied form.

I hesitated for one moment. This news of Lucy was not the main reason for my decision. It was simply the final straw which weighted the scale in favour of staying. It had made me realise, with devastating clarity, how much Fairacre ready meant to me. For that I should be grateful to Lucy always.

With infinite joy, I began to tear the application form into small pieces. Then—slattern to the last- I flung them in the direction of the waste paper basket, unmindful of whether they went in or not. I felt wonderful.

I bounded mto the sunlit garden—

my

garden—and positively skipped down the path. As I passed the water butt I let out a joyous shout to the sleeping cat.

'Fairacre forever!'

For two pins I would have run up the school's Union Jack.

10. The Wayfarer

S

TRANGERS

are rare birds in the village of Fairacre and cause us as much interest as any hoopoes. We have our annual migrants, of course, and are always eager to see them each year, but they are only half-strangers.

These half-strangers come mainly in the summer. One ready can't blame them. Winter comes with a vengeance here, with great roaring winds, cruel frosts and plenty of snow. As most of the visitors are townsfolk, they wisely remain where pavements, buses, indoor entertainment and central heating are available during the worst of the weather. But once spring begins, Mr Lamb, at the Post Office, recognises the handwriting of friends and relatives of Fairacre natives and looks at the postmarks of London, Birmingham, Bristol and Leeds, and nods his head wisely.

'Asking to come again, no doubt,' he surmises. And, usually, he is right.

As well as these people, we look forward to seeing half a dozen or so regular tradesmen. In May, a small flat cart pulled by an ancient donkey appears in Fairacre. On board are dozens of boxes of seedlings. Alyssum and lobelia for neat border edgings, tagetes and African marigold, snapdragons and stocks, and best of all, velvety pansies already a-blowing in every colour imaginable. Sometimes there is a box or two of rosy double daisies. These I can never resist, and each year they are drawn to my notice by the two dark-eyed gipsies, who do the selling.

'Lovely daisies, dear. Better than ever this year. We got new seeds, see. They was more expensive, but we'd let you have 'em the same price as last year, dear, as we knows you so well.' And so I have a dozen or so, as they knew I would, and probably pay more, for I can't possibly remember what I paid the year before. And this they know too.

While the transaction goes on the children cluster round the donkey, stroking his plushy nose and murmuring endearments. Somehow, the donkey cart always manages to call on a sunny day, at about one-fifteen, when the school dinner is over and the children are free to enjoy the fun.

'Miss, have you got a lump of sugar?' they plead.

'Miss, the donkey likes carrots, the man says!' cries another.

'Miss, have you got a bit of of bread to spare?'

It always ends the same way. Bearing my damp little newspaper parcels, and my much lighter purse, I return to the school house followed by the children and the gipsy woman. I hand over sugar lumps, old apples, the end of a loaf and anything else which, at a cursory glance round my larder, will make acceptable donkey-fodder, and watch the children tearing across the playground with their largesse. But the gipsy woman remains. Her eyes have grown very large and sad, her voice pathetic. She speaks quietly, as one woman to another, on intimate matters.

'I'm not one to beg, miss, as well you know, but the fact is I'm expecting again and hardly a decent rag to fit me. I'm carrying low this time, and not a skirt will go round me.' I wonder, inconsequently, if 'carrying high' would mean that her upper garments would be too tight, but hastily dismiss the idea.

She shuffles a little closer, and looks furtively about her. The whisper becomes a whine.

'Don't matter how old, dear. Or a coat, now. Say you had a coat. Don't matter if it's torn or grubby. Do us a good turn, lady, and see what you can find, if it's only for the sake of the baby.'

I tell her to wait, whisk upstairs, collect a dear faithful old flannel skirt, which I know I shall mourn later, a tartan jacket which Amy unkindly but truthfully told me made me look 'like mutton dressed as lamb,' and return.

The skinny dark hands grab diem quickly and turn diem inside out. The sharp eyes, I notice, are bright with approval.

'Thank you, dearie. God bless you! I've got no money to give you, with all we've got to feed, but I'd like you to have a pot plant off the cart.'

'No, really—' I protest. 'Just take the clothes.'

'You come on!' insists my caller. Meekly, I accompany her to the cart. The donkey, surfeited, is scraping the road with one neat little hoof. The scrunching of sugar lumps can be heard, but not from the donkey.

I choose a handsome pink geranium. We exchange civilities. The couple mount the cart. My skirt and jacket are stuffed under the wooden board that serves as a seat, in company with an assortment of other garments, I notice. We all wave until they are out of sight.

'Ring the bell, Ernest,' I say. 'It's time we were back to work!'

We install the geranium on my desk, as a happy reminder of one of our visitors. It will be a year before we sec them again.

Later, the scissor-grinder comes, and we rush out to his Heath Robinson machine with shears and scissors, knives and bill-hooks. Sometime in June, a stocky figure appears pushing a light barrow full of assorted materials and tools. This is the chair-mender and mat-mender. He does rushing, caning and a certain amount of simple carpentry. Doormats are the things he likes mending best, and I remember the pride with which he told me one day that my back-door mat was 'one of the finest ever made in one of Her Majesty's prisons.' I have no way of testing the truth of this statement, but I like to think that I wipe the garden mud from my shoes on a decent bit of British workmanship.

Then, in high summer, more gipsies come, bearing gaudy flowers made of woodshavings and dyed all the colours of the rainbow. Sometimes they bring clothes pegs, clamped together in rows on long twigs, still green and damp from the hazel bushes where the wands were cut and peeled.

All these people are known and welcomed. They are as much part of the season as the daffodils or the Canterbury bells. In addition we sometimes have a visitor of more exotic caste. Once a tad turbaned stranger, with dusky skin and flashing eyes, called at our cottages. When we appeared, startled, at our doors he chanted:

'You lucky lady! Me, holy man from Pakistan!' And after these opening civilities he displayed the contents of a large suitcase for our delectation. Writing paper, soap, bright ties, hair ribbons, toothpaste—all jostled together to tempt the money from our purses. But I don't think he sold a great deal in Fairacre, for he never came again. Nor did 'the antique dealer' who offered Mrs Pringle ten shillings for her grandfather clock, and Mr Willet a pound for the silver teapot left him by a former employer.

And another stranger, who called but once, was perhaps the most haunting of aU our visitors. I see his face more clearly than many of my childrens, and often wonder what happened to that shabby Utile figure who visited my house, long ago, and never returned.

It was a still, hot May morning when he arrived. The lilacs, tulips and forget-me-nots shimmered in a blue haze. It was a Saturday, and I had done my weekly washing. It hung motionless upon the line, but was drying rapidly, nevertheless, in the great heat.

I had dragged the wooden garden seat into the shade and was resting there, glorying in the weather, when I heard the click of the gate. A small man, carrying a battered suitcase slung over his shoulder with a leather strap, shuffled up the path. My heart sank. Must I rouse myself to face a jumble of assorted objects, none of which I really wanted, which no doubt awaited my inspection inside the case?

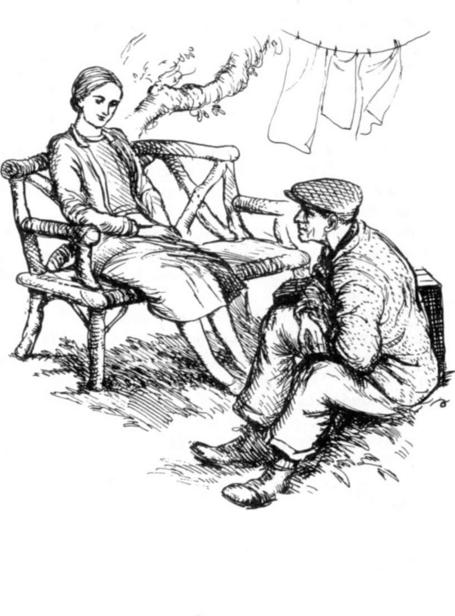

He did not stop at the door, but made his way across the grass towards me, slipped the heavy case from his back, with a sigh of relief, and spoke.

'Mind if I sit down, miss?' he asked. His voice had a Cockney twang and he sounded tired. I nodded and he sat abruptly on the grass, as though his legs would carry him no further.

We sat in silence for a few minutes, he too tired, I suspected, and I too bemused with the sunshine, to make conversation. A bumble bee buzzed busily about the daisies on the grass. It seemed to be the only thing that moved in the garden. At length, I roused myself enough to speak.

'Don't bother to undo your case,' I said. The man looked faintly surprised.

'I weren't going to. Why should I?'

'I thought maybe, you were selling things,' I replied apologetically.

'Got nothin' to sell,' he said laconically. He lay back on the grass with his eyes shut, and I studied him.

He was quite old. He was a man in his seventies, I guessed, looking at the grey stubbly hair and his wrinkled forehead. A red band ran round his damp brow, where his cap had been, and a little trickle of sweat crept down his temple. He had a humorous look, and I guessed that he was a cheerful sparrow of a man, in the normal way. At the moment he looked utterly exhausted, and my heart smote me.

'Would you like a drink?' I asked. 'I haven't any beer, but there's cider or lemonade.'

He sat up slowly, his face creasing into a smile.

'I'd like a drop of lemon, miss, thank you,' he replied. He took a red and white spotted handkerchief from his pocket, and I left him wiping his face and neck, as I went towards the kitchen for refreshment.

It was a relief to leave the dazzling garden for the cool shade of the kitchen. I loaded the tray with a jug of lemonade, two glasses and the biscuit tin, and returned. The stranger struggled up at my approach, and took the tray from me.

He poured one glassful of lemonade straight down his throat, sighed, and put it back on the tray.

'I could do with that,' he said, thankfully, watching me refill it. 'I bin on the road since 'arpars six.'

'Have you far to go?' I asked him.

'Making for Weymouth,' he said.

'For a holiday?'

'For good!' he said shortly. He looked away into the distance, turning his glass round and round in his rough hands. There was sadness in his face, but a determination about the set of his mouth that made me wonder what lay behind his journey. I was soon to know.

'I got an ol' friend in Weymouth. We was in the army together. Went all through the war—Ypres, retreat from Mons, the lot. Name of Miller—Dusty Miller, of course.'

He gave me a quick sidelong smile.

'We 'ad some good times together. And some narrer squeaks too. "You come down anytime you like," Dusty says to me, whenever we met. "Always a welcome at Weymouth," he says, "for an old comrade!" So I'm going!'

He scrunched a biscuit fiercely. He looked a little defiant, I thought.

''Course I shouldn't say this,' he said, swallowing noisily, 'but poor ol' Dusty picked the wrong girl when he got wed. Worst day's work he ever done, in my 'umble opinion! Can't think what come over 'im!'

He ruminated for a moment, crossing one leg over the other, and contemplated his battered boots. His spirits were rising with rest and refreshment, and his natural loquacity became apparent.

'Ol' Dusty,' he assured me with emphasis, 'could 'ave 'ad 'is pick of the girls. Fine set-up feller always. Curly hair, good moustache, biceps like footballs. Always ready for a lark. Why, in France—' He stopped suddenly, coughed with some delicacy, and started again.

'After the war, 'e 'ad a nice little packet of money saved up. His dad run a little confectioner-tobacco shop down die Mile End road, and when the old boy conked out in 1920 Dusty sold up and put the money into this caffy at Weymouth. Always bin fond of the sea, 'as Dusty, and I thought that's where 'e'd end up.'

'And so he's been there for a long time,' I observed.

'Ever since. Married a local girl too. Great pity really.'

He sighed, and helped himself to another biscuit.

''Course, you can understand it,' he continued. 'With this 'ere caffy to run, and that, you need a woman to lend a hand.

And

I must say, she could make two pennies go as far as three. A real 'ead for figures. It's thanks to Edie the place 'as done so well, but she weren't the woman for Dusty. No fun. Never one for a laugh. One of them stringy women, with a sharp nose. A bit white and spiteful, if you know what I mean.'