A 1950s Childhood (17 page)

Authors: Paul Feeney

As Christmas started to get nearer, your mum would have had a good tidy-up to make sure that everything

was spick and span for the big day. Positioning and decorating the Christmas tree, and hanging sprigs of holly and mistletoe from the ceiling, these were the things that signalled the start of Christmas in the home. Some people still followed the old tradition of putting candles on their trees for decoration … Well, there were a lot of burned-out houses around in the 1950s! However, in the main, the Christmas tree would be decorated with baubles, bells, ribbons, chocolate coins wrapped in gold foil, and balls of cotton wool to represent snow, with the customary angel or fairy doll perched at the very top of the tree. Christmas tree lights, or fairy lights as they were sometimes called, didn’t become popular in the home until the late ’50s, and then they were expensive and could be very dangerous. Your first ever set of fairy lights probably came from Woolworths – they sold everything.

A few days before Christmas, your dad splashed out threepence to buy his ‘once a year copy’ of the

Radio Times

to see what exciting Christmas treats were on the radio and television over the Christmas week. Mum spent a lot of time in the kitchen making the Christmas cake, Christmas (plum) pudding, mince pies and sausage rolls. And you wrote your letter to Father Christmas in Lapland, telling him what presents you would like and begging him not to forget you.

Christmas itself was really short-lived, and it was only on Christmas Eve that the Christmas celebrations at home really began; that was usually after your dad got home from work. People tended to work long hours and there was no such thing as finishing work early on Christmas Eve. The night before Christmas was, in many ways, more

exciting than the day itself. There weren’t many Christmassy programmes on the radio or television, apart from carol concerts, and you might be treated to an adaptation of Charles Dickens’

A Christmas Carol

. Mostly, everyone was busy, wrapping individual family presents or helping mum to sort out last minute jobs around the house. A number of people went to midnight mass at their local church on Christmas Eve, which for some was just for the novelty of it, and for others it was to satisfy a once-a-year twinge of conscience, but mostly it was regular churchgoers that went every year.

Every child went through the ritual of leaving something in the fireplace for Santa when he came down the chimney to deliver the presents, but once again your dad managed to skate around the perpetual question, ‘How will Santa get down the chimney without getting burned?’ You decide to give up on that subject; maybe your dad isn’t that clever after all! Instead, you pester your mum to see if it is time yet to put Santa’s glass of milk and mince pie in the fireplace. Dad suggests that you leave a carrot out for Santa’s reindeer, Rudolf, and that Santa would probably prefer a glass of Sherry instead of milk, but mum says that’s not a good idea because after a glass of Sherry he could fall off the roof!

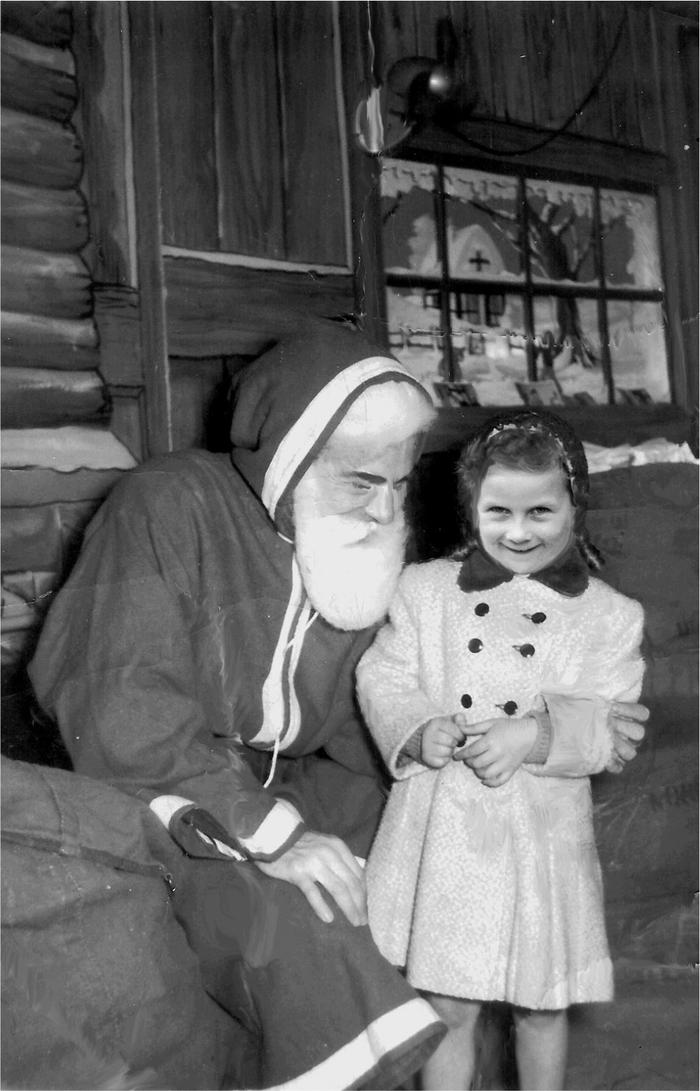

A shy young girl visits Father Christmas at Santa’s Grotto in Gamages department store in central London in 1955.

Suddenly, you are aware of the sound of carol singers in the street outside, and you rush to the window to see. There is a large group of people in the middle of the road holding song sheets and lanterns, and there are others going door-to-door collecting money. These are the last carol singers that you will see this Christmas and so you stay at the window to watch and listen, and your dad goes outside to

give them some money. With the carol singers gone, it won’t be long before you are tucked up in bed and dreaming the night away, hoping that Santa hasn’t forgotten to bring your presents. Having searched the house one more time, you are still unable to find any presents that your mum and dad might have hidden away from you, and so you go off to bed early in the hope that morning will come quicker. Before climbing into bed, you reposition the empty stocking (optimists used a pillow case) that is hanging at the end of your bed, just to be sure that Santa will find it easily and without having to search for it. Once in bed, you close your eyes and try to stay awake as long as possible, in the hope that you might see Santa when he comes to your house, but as the minutes tick away, you gradually slip into a dreamy slumber.

Soon it is morning, and even though it’s very early, not even the cold air in the bedroom can deter you from climbing out from under the blankets to investigate the bulging stocking at the end of your bed. Nothing too exciting in there, but you are very happy to find it filled with the usual Christmas mix of sweets and other goodies. You know that your parents are still sleeping, but you deliberately make noises to wake them up in the hope that the day can begin. After all, it is Christmas!

Family life was much more organised back then; people tended to get up at a routine time each day, even on weekends and holidays. Meals were usually at fixed times, and you were expected to be at the table on time. Although there wasn’t much difference in the way most families organised their Christmas Day, with breakfast, church, dinner, Queen’s speech, and sandwiches and cake

for tea; there was some inconsistency when it came down to opening presents. In some families, everyone just dived in once the whole household was up, with wrapping paper flying everywhere. Not a bad plan, because it gave children the whole day in which to play with their new toys and games, keeping them occupied, and hopefully quiet. Other families went to church on Christmas morning and the presents were left until after they got home. Different families had different rules for when presents could be opened, like after breakfast, or after Christmas dinner when all the family was together, or maybe when granny arrived. These were all very polite ways of doing things, but a bit mean on the kids!

There were always one or two children out in the street early on Christmas morning trying out their new roller skates or hula hoop, more so in the late ’50s when people were a bit flusher with money. It was pitiful to watch this from the window, while your own presents were still neatly wrapped up under the Christmas tree. Some kids weren’t even allowed out of the house at all on Christmas Day, which was hard to take if you got a new scooter for Christmas … real torture! Christmas presents improved as you moved through the ’50s and further away from the frugal post-war years. If you were lucky, you would get at least one big present, a wind-up toy, a big doll, an Airfix model or Meccano construction kit, or a board game or something. Almost everything else would be what adults would call ‘practical’, like socks or a set of cotton handkerchiefs with your initial embroidered in one corner of each hankie. Faraway relatives would sometimes send you money, and those were the best presents of all.

Everyone got dressed in their Sunday best on Christmas Day, even if they were staying at home. Typical 1950s dads didn’t do casual anyway, collar and tie was always the order of the day. The table was laid early for Christmas dinner, with all the best glasses and cutlery, and of course the Christmas crackers. The dinner always seemed to be served sharp at one o’clock, and it was somehow important to be finished in time for the Queen’s speech. Many families had roast chicken for Christmas dinner instead of the traditional turkey, as turkey was too expensive. Goose was also popular, but again, it was dearer than chicken. Your plate was filled to the brim with roast potatoes, stuffing, and all sorts of fresh vegetables. When you were stuffed full of Christmas dinner, your mum would bring in the Christmas pudding, into which she had already put some threepenny and sixpenny pieces. It was considered to be lucky if you found one in your piece of pudding – extra lucky if you broke a tooth on one! As was the tradition, your dad would pour some of his Christmas brandy over the pudding and set fire to it. You would then struggle to eat the smallest piece of what was a very rich plum pudding, whilst trying to avoid swallowing one of the coins that were buried somewhere inside it.

In between dinner and teatime you would munch on a variety of snacks laid out on the sideboard, from chestnuts to marshmallows. It was the only day in the year that you could really stuff yourself silly. At some point during the afternoon, you would be prised away from your favourite toy to go for a walk out in the fresh air, to ‘help your dinner go down’. On Christmas Day in 1956, you wouldn’t have needed much encouragement to go outside, because it was one of those rare Christmas days when snow fell in most areas of

the country and answered every child’s Christmas wish for a white Christmas. There wasn’t much to watch on television during the day, and most families only switched it on for the Queen’s speech at three o’clock (from 1957). There was often a live broadcast from a children’s ward at one of the hospitals, and

Billy Smart’s Circus

was usually on in the afternoon.

Later in the afternoon, just as you finished chewing on a date, your mum would start to serve afternoon tea. Cold turkey and ham sandwiches, sausage rolls and pickled onions, with lots of sweet things, like mince pies, Victoria sponge cake, fruit jelly and blancmange. After tea, mum would hand around her box of Black Magic chocolates that your dad had bought her, while dad would puff away on one of the half corona cigars that he had received. Apart from game shows, and perhaps a special drama production, the evening’s television highlight was the big variety show that the BBC put on every year, with all the best acts of the day. In the early ’50s it was the BBC’s

Television’s Christmas

Party

, a live variety show that was on for about an hour and a half, and featured artists like Arthur Askey, Max Bygraves, Tommy Cooper, Frankie Howerd, Bob Monkhouse, Terry Thomas and Norman Wisdom. In the late ’50s there was BBC’s

Christmas Night with the Stars

, a grander pre-recorded variety and sketch show, featuring artists like Charlie Chester, Billy Cotton, Charlie Drake, Jimmy Edwards, Tony Hancock, Ted Ray and Jack Warner.

Sometimes, families would play board games in the evening, and when there was a family gathering with aunts and uncles and grandparents, the grown-ups would have a singsong around the old upright piano, or play gramophone records and talk. They were all so old! And it was all so

boring! Later in the evening, when the novelty of playing with your new toys and games had worn off, you would all play cards together as a family, and you may even have convinced them to let you listen to one of your favourite gramophone records.

All of the day’s excitement and your continual gorging eventually took its toll on you, and you had to admit to being tired enough for bed. Tripping over the pile of gramophone records on the floor next to the record player, you sleepily make your way off to bed, while the grown-ups continue to play cards into the early hours of the morning.

The next day, Boxing Day, was still considered to be a family day when you stayed indoors, had visitors, or went to visit relatives. If you were lucky, you would get a couple of hours to play outside with your friends and try out some of their Christmas presents. Boxing Day was very much like a Sunday; all the shops were shut and there was nothing to do. The only available treat was a trip to the circus, if you had one within travelling distance of where you lived and your parents could afford it. Grown-ups had to go back to work on 27 December so Boxing Day was their last day off for a while (New Year’s Day wasn’t a national public holiday in the ’50s). Boxing day, therefore, was usually a stay-at-home family day.

In Scotland, Christmas was not celebrated to the same extent as it was in the rest of Britain, and up until 1958 Christmas Day was a normal working day. For almost 400 years Christmas was banned in Scotland, where it was seen as a Popish or Catholic festival. Scotland’s main day of celebration was Hogmanay (31 December) and it was celebrated with public holidays from 31 December – 2 January.

Sitting cross-legged on the floor, you move your knees up and curl your arms around them to make more room for the other kids sitting on the floor around you. You are aware that the room is full, but you are oblivious to who is actually sitting beside you because your concentration is fixed on the huge wooden cabinet in the corner of the room, just an arm’s length away from you. Your attention is broken for a moment when a grown-up leans over you and turns one of the knobs on the front of the cabinet – click! The room becomes hushed and you are now aware of a slight humming noise coming from the stretched brown and gold cloth that is set into the bottom half of the cabinet’s fascia. One of the boys starts to get impatient for something to happen, and a grown-up voice from behind tells him to be quiet, ‘Wait a minute, it needs to warm up.’ Soon, a picture starts to appear in the grey twelve-inch glass screen, which is set into the top half of the cabinet. Everyone stares at the silvery-grey moving images that are

now clearly visible on the screen, and the excitement in the room begins to mount.

On Tuesday 2 June 1953, an estimated 3 million people lined the streets of London to see the procession of their newly crowned queen, Elizabeth II. Most of them spent the night before dossing down on pavements to secure a good vantage point for the morning. By eleven o’clock on that Tuesday morning, the majority of the country’s remaining population had settled down to listen to the commentary on the radio, or to watch the live broadcast on BBC television, or at public venue screenings in cinemas, church halls and hospitals. Most of the television viewers had gathered in groups at neighbours’ houses to watch their queen crowned. All over the country there were rows of empty houses, where whole families had decanted into their neighbours’ crowded living rooms to watch the ceremony on tiny silvery-grey television screens; most screens measured only twelve or fourteen inches, but some were as small as nine inches.

It rained on the day, but that certainly didn’t dampen the celebrations. Memories of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation are etched into the minds of every 1950s child. It was the first time ever that a monarch’s coronation had been televised for all to see. It brightened up the lives of ordinary people who were still suffering economic hardship and scarcity in post-war Britain. The queen’s gold ornate coronation coach, and the extravagant ceremony with all

the dignitaries in their fine robes and jewels, gave ordinary people a peek into the land of plenty.

In 1953, in a street in central London, a group of young children pose for a picture to be taken just before their ‘Queen’s Coronation’ street party begins.

Children and adults gathered together for a ‘Queen’s Coronation’ street party in south-east London in 1953.

After seeing the wondrous real-life fairy story of royalty on television, the biggest celebrations began, with street parties in every town and village across the land. People brought out tables from their houses and placed them side-by-side to form one long table down the centre of the road. Everyone was enlisted to carry chairs from houses and line them up along each side of the extended table. The table was then dressed from end to end with lots of clean white tablecloths. Street lampposts were decorated, flags hung from upstairs windows and whole streets were decked out in red, white and blue bunting and cardboard cut-out royal crowns. There were all sorts of special coronation items for people to use and wear, like cardboard hats, paper aprons, bibs and napkins. There were loads of sandwiches, cakes and jelly, and everyone was happy and friendly. Most kids wore their best clothes or their school uniform, but some streets had fancy dress parties and the children wore a variety of outfits and strange homemade hats. The queen’s coronation was probably the most memorable 1950s childhood event, apart from the day sweet rationing ended! Oh, and the day you got your first ever television set.

Thursday 3 May 1951 was the official opening day of the festival at the main exhibition venue, which was at London’s South Bank site by the River Thames, near to Waterloo Bridge. The Festival of Britain was spread over a four-

month period and included a series of exhibitions held all around the country. It was organised in an attempt to provide the British people with a feeling that the country was recovering from all the destruction caused to its towns and cities during the Second World War. The exhibitions were intended to lift people’s spirits whilst promoting the very best of British design, science, art and industry. London’s South Bank site, including The Royal Festival Hall, was especially constructed to be the centrepiece of the festival. Other South Bank structures included the Dome of Discovery, a temporary building that was like an early version of the Millennium Dome, and the Skylon, an unusual cigar-shaped aluminium-clad steel tower supported

by cables – all designed in a modernist style. The festival also celebrated the centenary of the Great Exhibition of 1851, sometimes referred to as the Crystal Palace Exhibition.

Visitors to the Festival of Britain outside the Dome of Discovery on London’s South Bank in 1951.

Festival of Britain exhibitions were held in all of the main cities around Britain, but the most popular visitor sites were in London, with 8.5 million people visiting the South Bank Exhibition, and 8 million visiting the Festival Pleasure Gardens in Battersea. Most children would have enjoyed something about the festival, even if they were unable to visit any of the exhibition sites, because there were organised street parties all over the country, with bunting and Union Jacks everywhere.

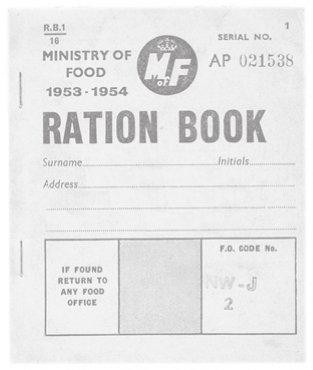

Food, clothing and petrol rationing was introduced at the start of the Second World War, but rationing got even stricter after the war ended, with bread and potatoes being added to the long list of foodstuffs in short supply. Children born in the 1930s and 1940s thought that it was normal to live with rationed amounts of food. The rationing rules were gradually relaxed from the end of the ’40s, but the biggest cause of celebration was when sweet rationing ended in February 1953, closely followed by the end of sugar rationing in September of that same year. Britain saw the final end of all rationing at midnight on 4 July 1954, when restrictions on the sale and purchase of meat and bacon were lifted. It was, by then, nine years since the war had ended, and fourteen years since food rationing had first begun.

It was the decade that television really started to overtake radio as the most popular form of entertainment in the home. Even as late as 1949, two out of three people in Britain had never seen a television programme. Television ownership really took off early in 1953, with people queuing to get one installed to watch the queen’s coronation. There was a further boost when Independent Television first started broadcasting commercially funded television programmes in September 1955. By 1957, radio audience figures had dropped significantly, with the BBC acknowledging that the nightly audience figures had fallen by one million in the last year alone, with more and more people moving to television viewing. By 1959, the number of British households with a television set had increased to 10 million. The numbers had been increasing at a rate of about one million each year for the previous six years. The 1950s was the age of television and it completely changed our way of life. It brought a wealth of new entertainment to everyone, but mostly to a generation of kids that had previously been starved of so many of life’s luxuries. There were loads of brand new children’s programmes, including some much-cherished and fondly remembered ones like

Crackerjack

(1955) and

Blue

Peter

(1958).

The ’50s saw the arrival of ‘rock and roll’ music in Britain for the first time (1954–6). This new wave of popular

culture was introduced to us through teenage films and records from the USA, with American rock and roll artists like Bill Haley and his Comets, and Elvis Presley the ‘King of Rock and Roll’. Britain had never known anything like it. It stirred British teenagers into life and had them jiving in the aisles at their local cinemas. Soon, ordinary British teenagers began to follow suit, buying guitars and forming their own skiffle and rock groups. It was the start of music careers for celebrated British artists like Lonnie Donegan, Adam Faith, Billy Fury, Cliff Richard and Marty Wilde. The rest is history!

All gramophone records were made in large size 78s (78 rpm) format until 1949 when RCA Victor developed the 7-inch 45-rpm single. However, few people owned a record player suitable for playing the new 45s, and so the older 78s continued to be sold alongside the 45s well into the 1950s. In 1958, Audio Fidelity in the USA, and Pye in Britain, issued the first stereo two-channel records, but we had to wait until the 1960s to see them sold in any quantity in Britain because very few people had stereo record players in the 1950s.