A Blaze of Glory (13 page)

Fritz Bauer had joined the army in his hometown of Milwaukee, the regiment assembled at Madison near the first of the year, finally mustered into official service as part of the Federal forces in late January, two months before. Like many in the state, Bauer was German, his father risking a great deal to escape the chaotic political turmoil that had spread through Germany in the 1840s. Fritz had been born on the sea voyage westward, and his parents had put every effort into educating their only child as an American. Unlike many of the Germans who now wore the blue uniforms, Bauer had virtually no accent at all, his parents adapting to their new country by learning and speaking only English, even in the privacy of their home.

His father was a sausage maker, had a small butcher shop in Milwaukee, the one throwback to the customs of the old country. On his first journey to the army camp, Bauer had been well stocked with a knapsack full of the kind of tasty provisions that had quickly disappeared. It was one of the first great lessons. No matter what treats they brought from home, they didn’t last long, either stolen or bartered away. The packages came later, of course, caring families doing what they thought was proper to keep their boys fed, but many of those arrived empty, if they arrived at all. As infuriating as that was, the greater surprise was the food the army provided. The army believed in bulk and speed and the least expensive fare that could be obtained, and the men suffered for it. Bauer had his share of the gripes well before they left Wisconsin, and it fueled his sympathy for any of the others who suffered from the dysentery, the most common ailment they had yet to endure. His friend Sammie Willis had a double dose of agony, the boat rolling just enough to afflict him with the liquid misery from both ends of his body. There were others who suffered from seasickness, few having any experience with that at all. For the most part the rivers were calm, but to men who had never spent much time on a boat, any motion at all stirred up a surprising kind of trouble. Even worse than the rations, the fresh water supplies had lasted only a day, and the volume of traffic on the river meant slow going for the enormous fleet of transports, supply boats, and the gunboats that protected them. If they needed water, it would come straight from the river beneath them.

If the horror of the food and water was the first great shock, the second was the weaponry. The first muskets they were issued had been Austrian, a curiosity to Bauer. But during the few times they were allowed target practice, the adventure of that was instead a nightmare. The Austrian guns were heavy, unbalanced, and unreliable, and some of the most unfortunate found out they could even be dangerous. More than one finger and a number of teeth had been left in the soil of Camp Randall. But the frustrated officers could only placate the men by pointing out that other companies had been given a type of Belgian musket, which seemed to kill as many people behind the breech as it did anyone in front. But then came relief. Just before they were scheduled to leave the camp at St. Louis, the Dresden muskets had come, and for the first time the men understood that their colonel might actually have some real influence in this army. The reputation of the Dresden had spread long before the weapons themselves, and Bauer quickly learned why. The Dresden was comparatively lightweight, far easier to load than the Austrian pieces, and Bauer found he could actually hit a target without fear of the musket blowing apart in his face. Grateful sergeants passed along the praises of their men, a gratefulness that quickly rose up the ladder, Colonel Allen himself offering thanks to the ordnance department that someone in the army had finally shown some grasp of the obvious. If those rebels truly intended to fight a war, these bluecoated troops had best be equipped with a weapon that might actually accomplish something on the battlefield.

Though many of the new volunteers held on to their enthusiasm for a glorious rout of the first enemy they might see, Bauer and many of the others first had to absorb a dispiriting reality. Even with the far more reliable Dresden, the men learned what the veteran officers already knew, that passion for the cause had nothing to do with marksmanship. For the most part, their drills focused on maneuver, men shifting from column into line, responding to shouted instructions and bugle calls, and to Bauer’s surprise, and the disgust of many, once they reached the army’s vast camps at St. Louis, the men were rarely given much in the way of target practice. Most of the lessons with the Dresden involved teaching the men how to load them, as quickly and correctly as possible. The officers understood, even if the men with the muskets did not, that there wasn’t enough time to train these men how to hit a target. This was never going to be an army of sharpshooters. The tactics of the high command were based on numbers, that if enough of these boys were massed shoulder to shoulder in the face of the enemy, their sheer volume might have some good effect. It had been hoped, of course, that the rebel commanders didn’t understand that principle as well. But that hope had dissolved, first at Bull Run, at Donelson, and just about everywhere else the two armies had collided. The rabble of this rebellion, those illiterate farm boys from cotton country who knew nothing of

soldiering

, had brought to the fight an alarming talent for shooting straight. It was the first lesson learned by the men who were now veterans, a kind of experience not yet a part of the 16th Wisconsin.

The regiment had gathered from every part of Wisconsin, many friends, brothers, old and young. Many were German, but many were not, and Bauer had made close friends with men from very different backgrounds. In the logic of those who knew little of European geography, Bauer was immediately tagged with the nickname Dutchie. It was common practice among the soldiers to devise the most creative and descriptive nicknames as they could. But the best Bauer could do with his friend Samuel Willis, was to stretch his first name to Sammie.

Bauer’s father had been as supportive of Lincoln as many who had escaped Germany, and other lands where political chaos meant repression and a dispiriting lack of freedoms. The immigrants in particular held tight to a patriotic fervor, why this young nation’s ideals had to survive intact. Bauer had no problem accepting the responsibility of joining the army and he shared that passion with most everyone around him. There were the shirkers, of course, the men who put on the uniform for reasons known only to them, reasons that had already resulted in the drumming out of the hard cases. There was supposed to be great disgrace in that, a ceremony that gathered the entire regiment as the man was forced to march past a gauntlet of drummers, sent on his way as a stark reminder that the army only wanted those who respected the uniform, or the job they had to do. But the officers had not expected there to be

so many

hard cases, many of them succumbing to temptations too easily available around the camps, mostly alcohol. It soon became apparent that if the army eliminated every man who failed to show some high standard of moral character, there wouldn’t be enough men left for a fight. Though the most blatantly criminal were still eliminated, the drumming-out ceremony gradually faded away. Bauer knew, as did his ailing friend Willis, that the annoying Patterson might have been one of those who had barely slipped through.

“

L

ine up! March off by platoon on my command!”

Bauer moved forward as quickly as the man in front of him, coughed through the clouds of black smoke, caught a single glimpse of Colonel Allen at the far side of the deck, waving the men forward. On the river alongside both sides of the boat, belching smokestacks poured out a dense cascade of stinking clouds, more boats than Bauer could count. He pushed forward in short steps, the sounds growing, not just voices, but machinery, the boats themselves. Out beyond their own vessel, the voices onshore were loud and official, and he saw the plank leading them down to the shoreline, a narrow strip of land squeezed tight against a tall embankment. Officers on horseback guided them to one side, a wide, sloping gap that rose up through the steep bank, a mass of men in some kind of order moving that way. He was part of a column, more horsemen pointing the way, and he began the climb, moved past clusters of officers, flags and aides gathered close behind them. He felt the jump in his stomach, not the agonizing sickness, but something else, excitement, could feel the strength, the great mass of blue troops driving up the hillside, like thick blue liquid pouring upward into a funnel. The bands were everywhere, close and faraway, a blend of discordant noise. He passed close to one now, a half-dozen drummers pounding away, a sergeant leading them in a rhythm that was no rhythm at all, and behind, men with fifes, squealing out something that had no resemblance to a song. But he was past them quickly, still climbing, marching alongside more lines of men, some from his own regiment, others, strangers, all moving in a dense mass up the sandy pathway.

At the top of the hill, the ground flattened out, and near the edge of the bluff he saw two log cabins, ragged and run-down, a meager sign of someone’s efforts to make use of the high ground as a trading post. Beyond the cabins was a wide field, filled with unending rows of white tents. Up in front of the column, he saw the colors of the regiment, knew to move that way, saw familiar faces doing the same. The men on horseback were familiar, too, Captain Saxe, and now Colonel Allen, waving them out toward a wide roadway. The dense column began to divide, some men moving away in another direction, following their own flags on another road that divided the field where the tents had been pitched. Around the tents, men were sitting, small groups, campfires, some watching the new men coming ashore, others already used to it, men who had been there for days now. Bauer felt the power of that as well, the army even greater than he imagined it, more fields beyond, tents again, flags and blue uniforms, artillery and horses and wagons. The noise grew, more bands, and now shouts, different, not officers, but men in civilian clothes standing in front of open tents that were dingy and gray. Bauer had seen this in St. Louis, the sutlers, merchants who followed the army, who had some unknown ability to bring their wares and their equipment to places where every army would be. He saw leather goods, hanging on long poles, tin cups and plates, blankets and shirts and now, the food. The smells caught him by surprise, but it was no accident that some of the merchants were taking the time to fry meat, using their makeshift smokehouses, the astounding odors reaching men who for too many days had eaten nothing but army swill. Bauer felt his stomach rumbling, but the sergeant was there, the permanent anger, no one stepping out of line. Bauer saw an officer riding up close to one of the tents, his sword drawn, cursing the sutler, the argument growing. More officers joined the fray, but Bauer couldn’t see any more than that, wondered if the man had the right to be there, or if the officers would just take what they wanted. In moments, none of that mattered, his focus on the men in front of him, the flag out beyond them. Saxe stared hard at the men in his command, the men marching away from the river, moving out into woods they had never seen, past ravines and creek beds, to find their own open fields and tree lines where they, too, would pitch their tents.

Behind them the empty boats were hauling up their planks, hoarse officers onshore directing the traffic, a continuing chorus of curses and commands, jumbles of orders for the boats to disembark, to clear the landing for the next in line. The men who came up the hill behind Bauer shared the same feelings, the enthusiasm, the excitement, so much anticipation for the

great adventure

. Some of the more curious turned to watch the boats, the flowing river nearly blanketed by the mass of vessels, moving in tight against one another, disgorging their men and supplies, horses and artillery. To the north, downriver, the procession was unending, so many columns of black smoke, drifting flat in a soft breeze, covering it all like a shroud.

SHERMAN

PITTSBURG LANDING, ON THE TENNESSEE RIVER MARCH 20, 1862

T

he ground was flat, dry, thick grass covering a wide field. To one side, the field fell away sharply into dense woods, and he saw men climbing up toward him, arms heavy with cut firewood. The camps of his division were almost complete, tents in long rows, most of them the large Sibley tents, capable of holding more than a dozen men. Already the fires were burning, thick smoke drifting with the wind, filling the treetops to the east. Nearly two miles that way, the river was still a massive logjam of boats, more men making the march inland. Most of them belonged to other divisions, spreading out in a pattern that seemed to make the best use of the geography. The open ground that spread west of the river was as General Smith had described it, high and mostly dry, sliced by ravines deep and shallow, some holding muddy water from the rains, some flowing away from small springs, clear clean water that the men found quickly. One of those was close to Sherman’s camp, a choice location. Filthy water had plagued the men in every campaign, dysentery pulling too many men off the line, taxing the doctors, weakening the entire army. He had chosen his own camp near a small crude church, and there, among the patchwork of open fields, he had made his headquarters.

He sat high on the horse, felt the satisfaction of a job done well, the camp already organized, officers moving among their men on horseback, doing their own inspections. To the south, beyond a narrow thicket he could see flickers of movement, more wagons and white tents. It was another of his fields, another encampment, one of his brigades already marching out into formation, the drills under way. It was the one point he had stressed to his colonels, that the men must begin their drills immediately. It had nagged at him at first, that so many of his men were green, fresh troops who had never fired a shot at anyone. He had placed most of those men farthest inland, where the open ground allowed better room for maneuver. To the east, toward the river, many of the fields were still a chaotic mass of wagons and artillery, all the hardware of the army. Every division had its own contingent of cannon and cavalry, and so Sherman had ordered his own cavalry to probe out westward, searching for eyes hiding in the woods that might be taking stock of what this massive army had put in place. Sherman knew that the army’s arrival at Pittsburg Landing had been no secret; there was never any chance that this much force could move through enemy territory without being observed. He knew as well that the rebel forces at Corinth, not more than twenty miles away, were increasing daily. It was the first report he had to make to General Grant.

THE CHERRY MANSION, SAVANNAH, TENNESSEE

MARCH 20, 1862

“Any estimate of numbers?”

Sherman tugged at his beard, shook his head.

“We’ve been able to send cavalry patrols as far as the railroad, but they don’t stay long. The rebels are out in force at every crossing, every bridge. What we know with certainty is that the rail lines are active. We’ve gotten that from the local citizens as well. There’s a lot of bragging going on out there. Even the loyal Confederates want to crow about how badly we’re going to be chewed up by their mighty army. One estimate said two hundred thousand troops had gathered at Corinth. One of the scouting parties, Major Pipkin, didn’t give that any credence at all. We know who some of the commanders are, Johnston of course, and Beauregard. Bragg is there, from the Gulf Coast, but Van Dorn is still a good ways away. The dirt farmers can crow all they want, but I doubt that any of those people, no matter how much they love their rebel flag, have any idea how many troops are down there.”

Grant looked at Smith, who lay on his back, a heavy compress on the damaged leg. Grant lowered his voice, said, “You put much stock in this fellow Cherry? He reliable?”

Smith seemed highly medicated, the room still stinking of the compress on his leg. He replied weakly, “Yes. He’s a Union man. Questioned him myself for quite a while. Besides offering us his rather elaborate home for our use, he’s sent a number of his servants out into the countryside. They’ve been giving us pretty accurate reports of rebel movement, mostly cavalry patrols.”

Grant looked around the room, scanned the furniture, glanced upward, seemed to appraise the ornate wainscoting high on the wall.

“Slaves, I assume.”

Smith nodded.

“I assume so. Didn’t really ask. He’s wealthy for certain, one of the big landowners around here. Grows a lot of cotton. Well, I suppose they all do. But he’s pretty upset by the war, and has no use at all for the rebel army.”

Sherman said nothing, withdrew a cigar from his pocket, and Grant caught the motion, did the same. The smoke quickly swirled through the room, and Smith said, “More Union people around here than I would have estimated. The commander of the gunboat

Tyler

, Lieutenant Gwin …”

Grant nodded.

“I know him.”

“He actually recruited some crewmen along the way. Seems there are more Union people in this part of Tennessee than we thought.”

Sherman pointed the cigar at Smith.

“Not too sure about the wisdom of that. Spies can be a crafty lot. We need to question these people thoroughly before we let them that close.”

Smith made a small laugh.

“Cump, the

Tyler

is sitting smack in the middle of the river. Unless those

spies

want to risk drowning, they’re staying put. What kind of secrets are they going to reveal, anyway? We have boats and troops moving south? Every cider merchant in a hundred miles of here has already set up shop somewhere between Savannah and Pittsburg. Tell you what, you see somebody nosing around your headquarters, you do what you want with him. I don’t think we have much to worry about up here.” Smith looked at Grant, seemed suddenly to acknowledge Grant’s authority. “If that meets with your approval, of course.”

Grant waved a casual hand toward Smith, shook his head. He still gazed at the décor in the room, fingered the cigar, kept his voice low.

“Impressive house. You’d think this is the kind of man who’d want us out of his hair, let him raise his cotton and do what he will with his slaves.”

Smith shrugged.

“No answer for you, Sam. Two sides to every equation. Mr. Cherry chose ours.”

Grant glanced at Sherman, then again at Smith, rolled the cigar between his fingers.

“You think Pittsburg is the best place to mass the army? There are other landings in both directions, plenty of room to maneuver.”

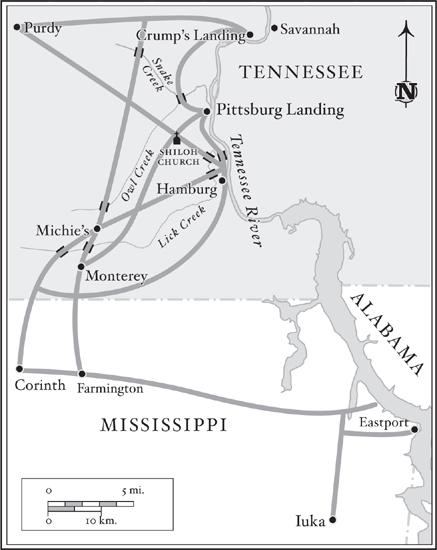

Smith nodded groggily. Sherman had chewed on this for a while, said, “I really don’t think it’s the best idea. If we spread out the five divisions … there are two more good landings to the south of Pittsburg … Hamburg and Tyler. You’ve ordered Lew Wallace to hold his division at Crump’s. So why not do the same with the rest of us? With this infernal weather muddying up every damn road, we ought to consider the advantage of using different routes toward Corinth, once we begin our operation. The roads do come together about halfway down to the rebel position. We can unite the army on the march.”

Grant shook his head.

“Thought about it. I want Lew Wallace where he is, in case we get struck by a cavalry raid. We’re vulnerable over that way, good roads that could bring the enemy right up our backside. But the rest … Pittsburg is a good place, and we should stay together.” Grant moved toward the closed door of the large room, opened it, called out, “Captain Rawlins!”

Sherman heard the response, closer than he expected, Grant’s aide obviously keeping close to his commander. Grant said, “You have that map of the area south of here?”

The staff officer responded crisply, and Sherman saw him now, younger, thin features, a full dark beard beneath piercing eyes.

“Right here, sir. I would be pleased to show you the details. I’ve spent some time studying the terrain—”

“Not right now, Captain.”

Sherman saw disappointment on the young man’s face, a nervous tick to the man’s hands, the same kind of habit Sherman had. Rawlins made a quick salute, which Grant returned, a gesture not necessary inside the house. Grant closed the door again, and Sherman caught the last glimpse of Rawlins’s face, the eyes of a neglected puppy. Grant moved to a table, spread the map, and Sherman couldn’t resist the question.

“Your staff officer been with you long?”

Grant stared at the wall for a second, seemed to weigh the question.

“Since August. But known him a great deal longer.” Grant spoke more quietly. “He is no doubt aware of what we are speaking of here. I would not accuse him of planting his ear to the door … well, perhaps so. But I cannot fault him for his protectiveness. But he does … hover over me sometimes. Reminds me of my mother.” Grant paused, was not smiling. “No, I cannot fault him. I need something, anything at all, he provides it. He provides things I didn’t even know I needed. Right now, he provided me with his absence. Sometimes that can be useful as well.”

Grant focused on the map, and Sherman finally saw the smile. Sherman said, “He sounds like the perfect chief adjutant. Sometimes, having our mothers in camp could be useful. Remind us we are not quite so … almighty.”

Grant nodded, kept his eyes on the map.

“Try it sometime.” Still focused on the map, he said, “If we may discuss matters at hand. You’ve seen this, I know. This whole area west of Pittsburg is protected by three major creeks, a natural defense, should we need one. Once we start the advance, we’ll already be united, and Colonel McPherson tells me the roads are best out in that direction. Your reports said that the roads anywhere close to the river aren’t suitable.”

Sherman nodded, tugged hard at his own cigar, a cloud of thick smoke boiling upward.

“They’re underwater, most of ’em. I gave up trying to put any force out toward the railroad. The only way we can make any progress that way is with cavalry. We’ll need more than horsemen to begin the assault. Artillery … well, Colonel McPherson will tell you, that’s out of the question. What doesn’t sink to its axles disappears altogether. This is the worst place for a campaign I’ve ever seen.”

CORINTH—SHILOH AND VICINITY

Grant rubbed his chin, studied the map, and Sherman tossed his spent cigar into a glass tray, brought out another one, stabbed it into his mouth. The smoke rolled through the room, and Smith seemed to perk up, said, “Cump, I’ve already told Sam, but you should know … I’ve recommended that William Wallace take over my division. My staff fought me on this. They won’t accept that I can’t just waltz out there and hop on a horse. Wallace is a good man. They’ll listen to him.”

Grant glanced at Sherman, and Sherman nodded his own approval. Grant said, “Yep. Mexican War veteran. General Halleck had him promoted right after Donelson. I agreed with that. But, dammit, how long you going to be laid up? From what I hear, you stubbed your damn toe. How long you plan to sleep in this fine old mansion?”

There was a hint of seriousness in the tease from Grant, and Sherman felt a stab of discomfort, saw Grant hesitate now.