A Blaze of Glory (35 page)

“Fine shooting, Dutchie. We took all they had and it weren’t enough. They went scamperin’ back to their mamas.”

Behind them, the sergeant called out, “Whiskey and gunpowder, boys! That’s what their generals feed ’em. Only thing that makes those damn secesh fight like animals. Well, not here! We took care of a pile of those devils!”

Bauer ignored Champlin’s bravado, stared out across the wide rolling field, the deep grass waving in a slight breeze, hiding the bodies that had fallen there. Bauer felt a sudden urgency, stared farther, to the dense woods beyond, where the rebels had retreated.

“They’ll be back.”

Bauer’s words came in a slow monotone, but Willis slapped his back, more joyous cheer in the man than Bauer had ever seen.

“Not all of them, Dutchie. Would you look at what they left here? We took half their strength, I bet. They wanna send out the other half, fine with me. But I bet they ain’t got the stomach for it, not for this!”

Bauer looked down, the musket in his hands, began the automatic motion of reloading, stopped, stared at the cartridge in his fingers. The words came out quietly, barely a whisper, to no one.

“How can they do that again? How many more times? This won’t end until we kill every damn one of them.”

Willis moved close to him, stared into his eyes, said, “Yep. That’s why we’re here.” Willis paused, studied him. “You all right, Dutchie? You ain’t fixin’ to go runnin’ off, are ya?”

Bauer pulled himself to Willis’s eyes, a brief glance, and he looked again to the musket, finished the job, the weapon quickly reloaded. He was prepared again.

“I’m all right, Sammie.” He tried to feel the cheer that was spreading around him, men calling out across the open field, more taunting, the joyous boasting of the victors. But the colonel was there, other officers, sharp calls, ordering the men into silence. Bauer saw Captain Patch, red-faced anger, the man pointing his sword into the orchard.

“Get down! Their artillery hasn’t found you yet! But that will change! You think this is over? They been charging our men to the right all day long! Get ready to receive another attack!”

The men responded with grumbles, curses, some still shouting across the wide grassy field to whoever might hear them. To one side, another horseman, brass, aides trailing behind, and Allen rode that way. Bauer watched them, always curious, and the colonel seemed to do the listening, gave a salute now, the higher-ranking officer moving away to the right.

He turned, whispered toward Willis.

“Who’s that? Some general. Doesn’t look like Prentiss.”

“None of our concern, Dutchie.”

Bauer watched as Allen rode closer to Captain Patch, the other officers on horseback coming up. Bauer stepped forward, close to the edge of the orchard, could hear the officers clearly, the colonel not hiding his words.

“They’re moving out farther to our left! No idea how many. Get everybody ready. I’ll ride to the left, make sure our flank’s protected. There are some Indiana boys down that way, and we need to stay hooked up close to them. Do the job, gentlemen. They’re coming again. Count on that.”

Bauer stepped deeper into the orchard again, found his place, saw the top of his tree shot to pieces. He knelt, could see the impact of musket balls that had split the tree in a half-dozen places, most just above where he had lain. He looked toward the dead Michigan man, still there, no time yet for stretcher bearers. Beside him, Willis hunkered down, checked his musket, said, “You hear the colonel? Hot damn, they’re coming again!”

Bauer ignored his friend’s strange enthusiasm, knelt down, checked the musket one more time, heard big talk filtering all through the peach trees, men marveling at their own victory, at the stunning surprise the blue troops had given the rebel advance. Some men had moved out in front of the orchard, as though counting the rebel dead, but the lieutenants halted that, the men ordered down, back into cover. Bauer lay low, suddenly remembered the wound in his arm, had forgotten completely, made a frantic motion, raising the arm, studied it. The shirt was torn, but not much else, and he rubbed his dirty fingers across a bloody scratch on his elbow, the small amount of blood already dried to a thin crust. He let out a breath, thought, close. Too close. Lucky … this time. No, don’t think on that.

He slid the musket up beside what was left of the peach tree, aimed, realized he was staring straight toward the man he had shot, could see the man’s legs still splayed out, one hand cocked upright in a grotesque curl, the rebel musket lying across the man’s leg. Bauer lowered his head, did not want to see that, said the prayer he had begun awhile ago. He scolded himself now, thought, stop this. This is why you’re here! That’s just one man, one damn secesh who would have shot you dead. You got him before he got you, that’s all. You probably got two of ’em. That’s what you’re supposed to do, ain’t it? And now, there’ll be more. The officer’s words came back to him now,

Hold your fire, aim low

. Yep, it worked. He laid his head down, his hat pressed against the base of the tree, saw the odd white carpet beneath him, the blossoms matted, dirty, churned up by the men and the fight. He closed his eyes, desperately tired, saw a rush of images through his head, Willis, the dead Michigan man, Colonel Allen, the captain, the vast mound of dead so close in front of them, the rebel falling … his rebel. One thought came now, pushing it all away.

God help us all.

JOHNSTON

SOUTH OF THE PEACH ORCHARD APRIL 6, 1862, 2:30 P.M.

H

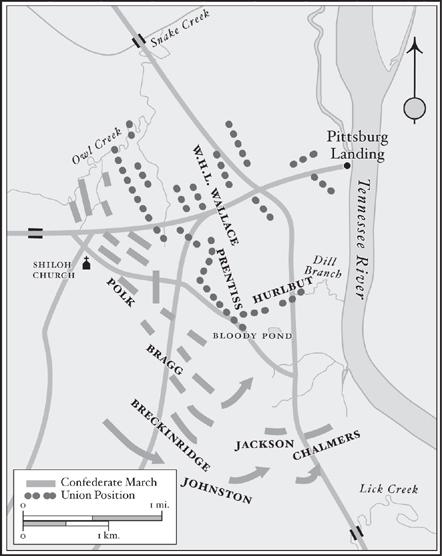

e was guiding many of Breckinridge’s men himself, showing the brigade commanders where to place their men, gradually extending Bragg’s position farther to the right. The artillery fire had been furious all through his movements, guns on the Southern side softening up any position of strength where the Federal troops lay. Across the way, Federal guns were sweeping the field with relentless destruction, men and horses in every one of Bragg’s advances cut down like so much bloody wheat. Johnston had spent more than an hour pulling the reserve troops into position, knew that by shifting Breckinridge forward, he was eliminating the reserves altogether. The reports flowing from Beauregard and from Johnston’s own staff had convinced him that there was no need for added strength to be sent to assist his left, that the Federal lines closer to Owl Creek were spent, offering little except defensive fire. What was now the center had become a bloodbath that Johnston had never expected, Bragg continuing to send troops across the open fields straight into a stubborn Federal position.

There had been no great coordination to the assaults, Bragg seeming to piece together whatever units he could grab at the moment, launching them forward to fill the space where already the casualties had been horrific. Johnston had observed several of those assaults himself, could see that Bragg was trying to break what had become a stalemate, that the Federals had planted themselves into good, strong ground, their lines far stronger than he or Bragg had anticipated. But farther to the right, the river wound along the flank of the entire battle like a great inviting serpent, a siren call to Johnston that he could not ignore. The closer he rode toward the river, the louder that call became, and the scouting reports seemed to disprove anyone’s theory that the Federals were massing there for an attack against Johnston’s right flank. To be sure, there were bluecoated troops in those woods, but the going there was rough, the thickets more dense, the ravines deeper, boggier, swampy creek beds that Johnston now understood could suck men down into immobility.

He would not order Bragg to change his tactics, the attacks at least serving the valuable purpose of drawing other troops from the more distant Federal positions to move to the center, offering assistance to the battered troops who repeatedly drove Bragg away. Already the gaps that Bragg had targeted on the flanks of Prentiss’s Division had been filled, word coming from prisoners and Bragg’s own scouts that Prentiss was receiving considerable help from the Federal divisions of Hurlbut and William Wallace. Bragg continued to insist in the most violent terms that he would eventually break the Federal position, but if Bragg had hopes that Breckinridge would send his corps in to assist that effort, Johnston had other ideas. Breckinridge was ordered out to the right of Bragg as far as he could maneuver without pulling a mass of Federal troops his way. It was Johnston’s effort, finally, to turn the Federal left flank. No matter what Colonel Jordan had drawn out on paper, it was clear to him now that this should always have been the plan, to drive in along the river and sever the connection the Federal troops had with Pittsburg Landing.

He rode now holding that thought in furious silence, directing the reserve troops out to do the job that should have been done by Hardee and Polk from the first skirmishes that morning. He had not seen Beauregard, knew only that the man was still suffering from his illness, had moved in an ambulance to the place the maps showed as Shiloh Church, what was now the army’s headquarters. But Johnston had no time for consultation, knew that if he were to meet with Beauregard right now, there would be an explosion that rivaled anything on this field. He despised that about himself, that he had the capacity for such anger, had almost never revealed it to anyone at all. But throughout this day, that anger had festered and swollen, made so much worse by the obviousness of the mistake. He fought to avoid thinking of Jordan, the colonel who even Bragg had suggested was pulling the Creole’s strings, the weakened Beauregard little more than a dancing marionette. It was an unwise and indiscreet observation from a subordinate, but he could not explode at Bragg, knew the man had to be allowed to do his job. After two hours of observing the carnage that Bragg seemed unable to stop, Johnston had left the man to his duty. Riding out in front of Breckinridge’s approaching troops, Johnston could not escape the sense that by leaving Bragg to batter himself against Prentiss’s stout defense, Johnston was making his

own

mistake.

No matter the earlier successes that had come on the left flank, Johnston had become obsessed with the right, that the final success of this day could come in only one place, and that was where he rode now. Breckinridge’s men had marched out into the same kinds of open grassy fields as the entire army had done all morning. They pressed forward through artillery fire, seeking safety behind ridgelines or dropping down through deep cuts choked with briars and vines. But this time, no matter what the Federals might do to counter the move, Johnston would not hold back, would not offer a

plan

for anyone’s discussion. This time his troops would smash the Federal flank and open a clear passage that would drive a stake northward, closer to the river, that would sever Grant from the heart of his army. Even Breckinridge understood he was no longer the reserve. He was the fist that Johnston would use to decide this fight, a fight Johnston knew could end with Grant surrendering his sword.

“

W

ho is that on the far flank?”

Johnston stared to the right with his field glasses and Munford responded, hesitation in his voice.

“General Chalmers, sir, I believe. There is much confusion.”

“No confusion there. Chalmers is Bragg’s man. Bragg sent him out there to feel for the enemy’s flank, and I don’t hear anything but scattered fire. That can only mean the enemy is not yet in strength there. We must occupy this ground to support him. Is General Breckinridge moving with haste?”

“Yes, sir. The orders were specific, and the general agreed to put his men to double speed. Statham’s Brigade is already moving into place to the right of General Bragg’s main position and General Bowen is following. They should both be in position very soon.”

Johnston turned, looked back through the woods, a field beyond, away from the ongoing Federal fire. He saw them now, fresh lines of troops coming forward, their drummers keeping time, their flags flying with brisk snaps in the breeze. A cluster of officers moved forward, and Johnston knew the man who led them, Winfield Statham, his brigade mostly from Mississippi and Tennessee. Many of those were green troops, no experience at all, but Johnston had confidence that Tennessee men in particular would fight this day, that no one among them would mistake the cause that brought them to this field. They were, after all, driving the invader from their own soil. Johnston focused again to the front, scanned a wide cotton field, one log cabin on the far side, and to the right of that, a peach orchard.

“Major, ride back to Colonel Statham. Request in the strongest terms that his brigade move into position so that he may advance toward that peach orchard. Bragg’s people have done no better there than they have against Prentiss.”

He saw a horseman, one of Bragg’s couriers. The man reined up the horse, saluted him, said, “Sir, General Bragg offers his compliments and reports that the enemy has been compelled to withdraw from that peach orchard, and has established a defensive position farther back in those far woods. General Bragg wishes you to be informed that he is pleased with that progress, sir.”

“Well, I am not pleased, Sergeant.” Johnston stopped, thought, this is not the time. “Sergeant, does General Bragg know who is in command over there? What enemy are we facing?”

“General Hurlbut, sir. According to the prisoners.”

Johnston looked out toward the distant tree line.

“Yes, I know him. Southern man, from South Carolina, I believe.” He glanced back at Munford. “We lost that one, Major. We shall make General Hurlbut pay for his unwise decision to fight against his own people. General Bragg is facing a stalemate, and I have no patience for stalemates. I much prefer checkmates. Major, you will instruct Colonel Statham to attack across this field as quickly as possible. Is General Bowen close behind him?”

Another of his staff spoke up, Colonel Preston.

“Yes, sir! I have just returned from that position, sir, behind those far woods. He is on the road that leads out that way, closer to the river.”

Johnston raised the field glasses to his eyes, searched the woods to the right of the peach orchard, nothing to see.

“It appears the enemy has withdrawn to thick cover. It is a position of strength. We must drive them away, turn that position, or I will be compelled to order Bragg to halt his attacks. There is no purpose to crushing our army against a stone wall unless that wall will break. Colonel Preston, return to General Bowen and order him to link his left to the right of Statham. I want a coordinated attack against the enemy’s position, and I will not accept failure. General Prentiss has shown a stubbornness I did not expect, but I will not believe that General Hurlbut will stand up to us, not if we strike him hard, and in concert.”

Preston rode away quickly, and Johnston still watched the field, thought of Bragg. So much confusion, and Bragg is an impatient man. We could not move in concert against such a scattered enemy, and Bragg’s impatience caused him to attack with whatever he had at hand. Piecemeal assaults. Well, there will be nothing piecemeal about what will happen now.

T

he attacks had begun as Johnston hoped, a hard-driving wall of power that stormed the Federal position in one great wave. Already the Federals were pulling back farther from their dense brush lines, the protection of the blasted orchard near the lone cabin. The bluecoated troops had endured so many assaults that the added strength now sent against them forced a retreat, Hurlbut’s men drawing back into dense woods and gullies that would make any fight or any retreat that much more difficult. As Breckinridge’s troops did their work, filling between Bragg’s forces in the center, the two brigades Bragg had sent toward the river launched attacks of their own, exactly what Johnston knew was needed to end the repeated carnage in front of the enemy forces commanded by Prentiss. But the reports came that Prentiss was mostly holding his ground. Johnston could see for himself that Prentiss’s left was beginning to turn. But there seemed to be no great panic in the Federal lines, their withdrawal slow and methodical. Even in retreat, the Federal troops continued to fight, and so, for both sides, the cost was horrifying. What Johnston could not see, he could hear, the astonishing storm of musket fire matched by a torrent of artillery shells, launched by both sides. He continued to move to the right, stayed up close behind the lines of Breckenridge’s troops. The progress of Breckinridge’s assaults, along with the advance of Bragg’s brigades under Chalmers and John Jackson, were opening up the gap nearer the swampy ground that bordered the river. Johnston heard it all, could feel the army moving as one great beast, seeking the opportunity he knew would decide the fight, to slice Grant’s army away from its base.