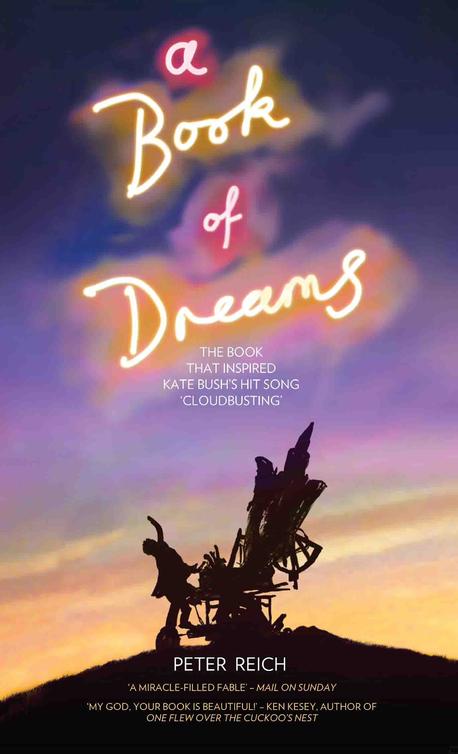

A Book of Dreams

Authors: Peter Reich

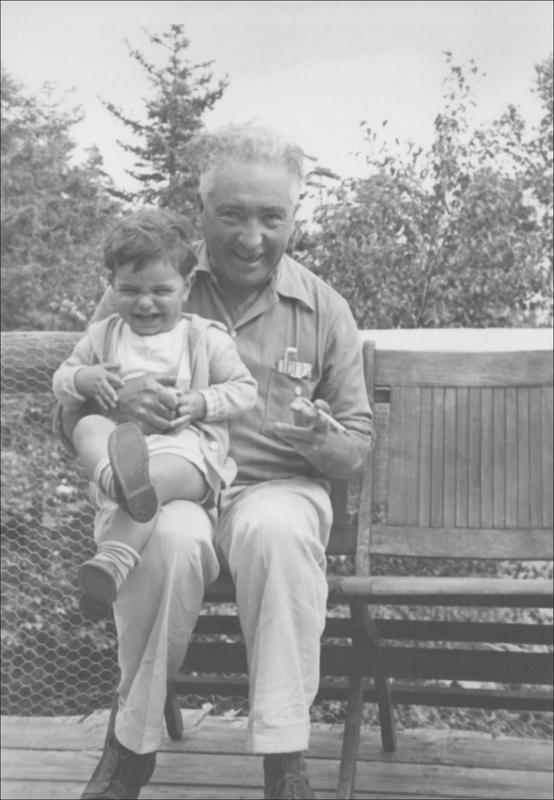

Peter Reich with his father, Wilhelm.

I CAN THINK of no better way to celebrate a new edition of this memoir than by extending warm thanks those who made it happen: my agent, Alison Bond who has represented

A Book of Dreams

diligently and patiently for more than twenty-five years; John Blake, Toby Buchan and Claire Chesser of John Blake Publishing, and Christian Furr for a cover that glows in the dark. Frederik Rusch, Nicholas Reich, and Susan Gulick offered helpful suggestions on the new preface. For Kate Bush, I unfurl my umbrella.

The author and publishers would like to record their gratitude to Christian Furr, not only for his jacket artwork, but also because he it was who suggested republishing

A Book of Dreams

in a new edition.

Love, work and knowledge are the wellsprings of our life: they should also govern it.

WILHELM REICH

THAT THIS LITTLE book should find readers four decades after it was written and six since Wilhelm Reich’s death, suggests that something in the story it tells continues to radiate his energy.

He was larger than life. He radiated heat. Women looked at him the way men look at women. To one scientist observing Reich at the 1948 international conference at Orgonon, he appeared to be surrounded by a blue aura.

In many ways, I deeply regret that the memories shown here have likely enhanced Reich’s image as a mad scientist, chasing flying saucers and changing the weather, toying with cosmic energy. But I did not make this up. What I witnessed was only the final, terribly sad act in a drama that began in vibrant Vienna

in the 1920s and 1930s and ended in a US federal penitentiary in 1957.

What really happened?

Having trained in Vienna with Sigmund Freud, Wilhelm Reich, MD (1897–1957), arrived in the US in 1939, where he built a private practice in New York City. There, his ideas about human character, sexuality and social psychology attracted a circle of students and a wide following. Working with Theodore P. Wolfe, MD, a Swiss-born psychiatrist, he translated his books from German to English:

Function of the Orgasm

(1942),

The Sexual Revolution

(1945),

Character Analysis

(1945),

The Mass Psychology of Fascism

(1946). Summering on the pristine lakes of Rangeley, Maine, he discovered what he called Cosmic Orgone Energy. Accumulated in small specially constructed, telephone booth size boxes, this Orgone Energy, he reported, was successful in healing wounds and restoring life energy. Yet another device, the Cloudbuster, appeared to control the weather. Then, his life turned into a Grade B science fiction movie.

While the main focus of this autobiographical memoir is a loving, tender father-son relationship, the reader will gain an uncommon glimpse of enigmatic, controversial Wilhelm Reich at his 200 acre hilltop home in Maine where he stroked the skies, watched the aurora borealis pulsate, and made devices that captured energy. By the early 1950s a combination of events brought his work to an end. Reich’s books were banned and burned and his devices destroyed by the US Government in 1956. Sentenced to prison for violating an order to cease shipment of Orgone Energy Accumulators across state lines, he

died in the Federal Penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, on November 3, 1957.

Today he is remembered commonly as a mad scientist, pornographer, and creator of the Orgone Energy Accumulator.

Time

magazine included Wilhelm Reich in its end-of-the-twentieth-century issue devoted to ‘The Century’s Greatest Minds,’ but as a ‘crank’. More recently he has been acknowledged as the father of the Sexual Revolution, although his important contributions to psychiatry, sexuality, and social psychology – published before he left Europe in 1939 – remain undervalued, under-appreciated, and, some would argue, suppressed.

But no one fully understands how things unravelled, or why.

Consider the forces that opposed Reich in the early 1950s: after failing to halt Reich’s work by declaring him a spy or a Communist, the Government accused him of fraud for claiming a cancer cure. At the time, The US Food and Drug Administration was doing its best to protect the public from widespread fraud in the market for pharmaceutical products and medical devices. Reich’s Orgone Institute was included on a long list of businesses pitching worthless products to a naive and gullible public. By one estimate, by the 1950s, some 4,000 quacks were fleecing thousands of victims – who had or feared they had cancer – out of about $50 million every year. The agency was eager to secure successful prosecutions on the road to gaining legislative authority to assure the efficacy – not simply the safety – of medical products sold to the public. Reich was an easy target. After three years of preparation the FDA issued in February, 1954, an injunction prohibiting transport of Orgone Energy Accumulators across state lines. After some

accumulators were shipped across state lines, he was taken to court and tried in 1956. He lost.

In the realm of psychiatry, much was changing rapidly. When young psychiatrists entered the field in the thirties and forties, as did many of Reich’s students, the field was chaotic. Many state hospitals were filled with patients insane with final stages of tertiary syphilis, nutritional disorders such as pellagra, lead poisoning and other organic diseases. Even for patients with anxiety, depression, and neuroses, the well-meaning psychiatrist could offer little in the way of established, effective treatment protocol. As one psychiatrist trained in the 1950s told me, ‘if you don’t know what to do, you do weird things.’ Many of these institutionalized patients were subjected to sterilization or castration and incredible experimental practices such as electroconvulsive therapy, focal sepsis, and lobotomy.

Onto this scene military psychiatrists having tried Freudian methods successfully on overseas battlefields arrived home eager to develop these effective techniques. Among newly arrived European immigrant mentors, Wilhelm Reich had developed a non-invasive, non-pharmaceutical therapy that produced exciting results. In addition to his penetrating deconstruction of Nazism in

The Mass Psychology of Fascism,

Reich was quite well-known for his clinical success in Vienna and for his disarming candour about the centrality of sexuality in one’s character. Character Analysis, as he labelled his method, recognized the overwhelming importance of social environment for character formation, specifically, that ‘the social origin of a person is fixed in frozen form in his character.’ Character Analysis evolved into Vegetotherapy and later Orgone Therapy.

He wrote, ‘I took the decision to step from analyzing neurotic systems through thought-thought association to removing the armouring of the organism through character analysis.’

He listened, observed, and then touched, prodded and probed, following an uncanny instinct for where on one’s body the memories, the hatred, the fear, were frozen. The therapeutic session entails loosening the armoured segments that stifle and frustrate the flow of bodily energy which, unhindered, finds release and pleasure in sexuality and enhances the capacity for love, work and knowledge. The therapy lies not simply in learning how to breathe and pulsate, but also in wrapping the experience in words of understanding. Only recently has there been some acknowledgment that Reich’s work spawned the body-therapy movement.

And then, in 1953 the first drug therapy for psychiatric patients that seemed to ‘work’ – Chlorpromazine – was introduced. The subsequent explosion in psychopharmacology and other modes of quick fix therapy – such as cognitive and behavioral therapies which, in general, do not address underlying, emotional conflicts – has rendered much Freudian psychotherapy nearly obsolete.

That same year, Watson and Crick described the structure of life as a double helix, and overnight, any alternate theory of the basic nature of life itself became irrelevant. Until 1953, it wasn’t entirely clear what fundamental process governed life: was it an identifiable particle – a ‘God particle’ – or some vital biological force? Proponents of Vitalism pursued the idea that the directive principle of life is not chemical or mechanistic, but instead some as yet unidentified force or energy. Reich lived, loved, learned and worked in Vienna at a time when Vitalism thrived; his

discovery of Orgone Energy can be understood to a large extent by his uncanny ability to find and unlock in the human body that pulsating, quivering, and melting and to see it as ‘an expression of man’s cosmic existence.’ In 1945, he concluded that ‘the genital embrace in the whole biological realm is a variety of the superimposition of cosmic primordial energy as expressed, e.g., in the formation of spiral galaxies and hurricanes.’ However, once Watson and Crick had described Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), any body of science that was not based on mechanical and chemical reactions among particles was effectively invalid.

These three factors: the discovery of DNA, the revolution in psychopharmacology, and the FDA’s campaign to require demonstrable efficacy of medical products have come to resemble in my mind a huge, immovable wall into which Reich, a great irresistible force, crashed in 1953.

Where do things stand today?

In 1930, Reich provided the intellectual rationale, a kind of psychosocial substrate, for the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s. But what actually triggered change was the 1965 US Supreme Court Decision, Griswold vs. Connecticut, which legalized contraception. In addition, newly introduced pharmaceutical ‘magic bullets’ had eliminated most sexually transmitted disease, removing another huge barrier to freer sexuality. But the potential of more open attitudes toward sexuality, and thus a greater capacity to combine love, work and knowledge as the wellsprings of our lives was hijacked by Madison Avenue. The feeling of deep longing – the need for fulfillment that is only gratified by melting love – this deep human need was grafted by Madison Avenue onto our acquisitive nature. As described by Christopher Turner

in his 2011 book

Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came to America

, Edward Bernays, Freud’s nephew who founded the country’s first public relations firm in 1919, ‘consciously used Freud’s idea of a latent but powerful sexuality as a form of subliminal seduction to manipulate the masses.’ What we see today is not the sexual revolution envisioned by Reich. This hyper-sexuality and the pornographizing of every-day life presented in 3D, HD, full colour, 24/7/365, delivers a message only about need – deep unfulfilled need for tenderness and loving.

Orgone Therapy, practiced by a well-trained therapist, can help unhappy, unfulfilled people feel the streaming between the legs and engage in satisfying and fulfilling lives. And, yes, I am open to the possibility of a life energy, a force connecting all things that will prove to be far less than what is believed by the devout, and a great deal more than can be measured or quantified in any way by a scientist.

This observation about Isaac Newton and gravity summarizes the way I see it:

Newton was able to imagine this black magic moving the apple because, as one biographer admiringly writes, ‘he embraced invisible forces.’ And he did so more promiscuously than we choose to remember. The inventor of modern gravity was also a fanatical alchemist. It’s just that, in the case of universal gravitation, the invisible force he embraced turned out to be real.

Reich grabbed the force for a time. It is real, it is blue, and it pulsates.

All of that happened a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, witnessed by a pre-adolescent lieutenant in the Corps of Cosmic Engineers.

This is his story.

P

ETER

R

EICH

, 2015

NOTE

: In this preface, quotes from Reich are from ‘The Developmental History of Orgonomic Functionalism’,

Orgonomic Functionalism

, Vol. 1, Spring 1990; the quote about Newton and gravity is from Jon Mooallem, ‘A Curious Attraction’,

Harper’s Magazine

, 315 (1889): 84–91, 24 October 2007. Chris Turner’s book was published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2011. More detail on the Food and Drug Administration and medical devices can be found in James Harvey Young’s

The Medical Messiahs: A Social History of Health Quackery in Twentieth-Century America

, Princeton University Press, 1992.