A Book of Great Worth

Read A Book of Great Worth Online

Authors: Dave Margoshes

Tags: #Socialism, #Fiction, #Short Fiction, #Jewish, #Journalism, #Yiddish, #USA, #New York City, #Inter-War Years, #Family, #Hindenberg, #Fathers, #Community, #Unions

© Dave Margoshes, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll-free to 1-800-893-5777.

This story collection is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Edited by Geoffrey Ursell

Cover designed by David Drummond

Typeset by Susan Buck

Printed and bound in Canada

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Margoshes, Dave, 1941-

A book of great worth / Dave Margoshes.

Issued also in an electronic format.

ISBN 978-1-55050-476-7

I. Title.

PS8576.A647B66 2012 C813'.54 C2011-908477-5

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Margoshes, Dave, 1941-

A book of great worth [electronic resource] / Dave

Margoshes.

Electronic monograph in EPUB format.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-1-55050-704-1

I. Title.

PS8576.A647B66 2012 C813'.54 C2011-908478-3

Available in Canada from:

2517 Victoria

Avenue

Publishers Group Canada

Regina, Saskatchewan

2440 Viking Way

Canada

S4P 0T2

Richmond, British Columbia

www.coteaubooks.com

Canada

V6V 1N2

Coteau Books gratefully acknowledges the financial support of its publishing program by: the Saskatchewan Arts Board, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Government of Saskatchewan through the Creative Economy Entrepreneurial Fund and the City of Regina Arts Commission.

This book is dedicated to the memory of my father, Harry Margoshes (also known as Morgenstern), 1893-1975

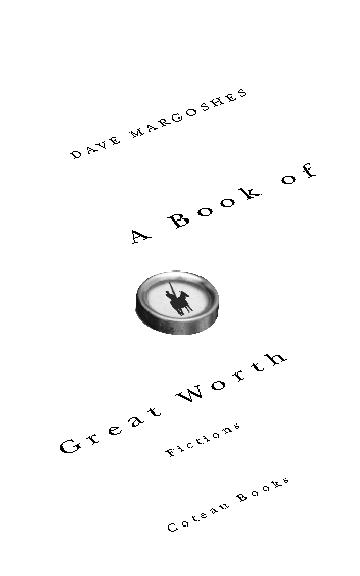

About the sketch

Harry Margoshes, at his desk at

The Day

sometime in the Nineteen Forties, as depicted by the paper’s

editorial cartoonist, painter Josef Foshko

• • •

The Proposition

“I did something stupid,” the rabbi told my father.

It was 1925, New York City, a bar on the Lower East Side.

My father was a few years away from marriage, fatherhood

, respectability, and so was prone to do stupid

things himself: stay up late, associate with rough customers, drink too much, sing off-key – which really was the only way my father knew how to sing. But a rabbi doing a stupid thing? And not just any rabbi, but his good friend Lev Bronstyn, who was more like a big brother to him than any of his own big brothers were.

“I’m not joking, Harry,” Bronstyn said. “I mean

really stupid.” He took a sip of whisky. “It involves a

woman.”

“Ah,” my father said.

“It’s bad, Harry,” the rabbi said. Bronstyn had a long, often damp nose and prominent ears, which combined to make his head appear larger than normal. He shook it now. “Very bad.”

•

••

My father was not a religious man, but he lived in a religious world. Sometimes those two forces – one pro, the other not necessarily anti but neutral – came together in a powerful, even violent clash.

More than three million Jews lived in the New York City of the Twenties and Thirties, more than the total population of some states, and the Lower East Side, where my father worked, was their capital. Many of them, if not most, were religious, at least to the extent that they believed in God, went to

shul

, kept kosher,

honoured and sought the counsel of rabbis. My father did none of these but he didn’t make a show of it. He was a Jew, he thought, but not Jewish, a fine distinction.

He was, by his own reckoning, a socialist, a humanist, an autodidact, and, to the extent that he could be, a freethinker and an intellectual. The religious instruction he’d had as a child in Galicia, in Eastern Europe, had come to naught – after the family moved to America, around the turn of the century, interest in religion had

waned for all but my grandmother who remained de

vout until her death, and my father was working as a blacksmith’s helper at a stable on the Bowery on his thirteenth birthday and never did have his

bar mitzvah.

That was a loss his mother, my

bubba

, regretted, but he didn’t.

By the time he began to write for

Der Tag

or

The Day

, all thoughts of religion were far behind him, although the newspaper conveyed a conservative

slant that appealed to religious elements in the Jewish

community. Soon he began to cover labour and was fre

quenting the Café Royale on Second Avenue and the Garden Cafeteria, just down the street from

The Day

building, hanging around with poets and playwrights, socialists, communists and anarchists, people who had no use for religion.

So it was a little strange that one of my father’s best friends during this period of his life was a rabbi.

•••

Bronstyn called on my father at

The Day’

s

offices at 187 East Broadway one Monday around noon and they walked the block and a half to a tavern on Henry Street where they could have a lunch for just a nickel extra with a beer. It was too crowded and noisy to talk but my father could tell something was on Bronstyn’s mind. After a while, when the crowd had thinned somewhat, they bought shots of whisky and moved to the booth at the end of a long row of them.

“I did something stupid,” Bronstyn began.

“It’s about time,” my father said, smiling. “You’re altogether too smart for your own good.”

“I’m not joking, Harry,” Bronstyn said. “I mean really stupid. This is bad.”

“What could be so bad?”

“It involves a woman.” He took a handkerchief from his jacket pocket and wiped his nose.

“Ah,” my father said. He was still a young man, with

relatively little personal experience with women, although

he’d had a bittersweet romance in Cleveland a few years earlier. But he was a keen student of human nature, and he’d observed that when men were in trouble it almost always involved a woman, to some extent at least. His stint as an advice columnist in Cleveland had certainly confirmed that.

Bronstyn was frowning at his drink, silent, and after a minute my father nodded his head and asked, “Surely not one of the women from those houses?”

“Yes,” Bronstyn said.

Immediately, my father gave his full attention to his friend.

Bronstyn, on completion of his theological studies, had declined a position as a working rabbi. Instead, he had pursued a career in social work, and was now employed at a large Jewish agency that gave assistance

of various sorts to orphans, unwed mothers, battered and otherwise abused women and children, and people of both sexes dealing with the deleterious effects of poverty. White slavery, the term applied to the mixture of sweet talk and intimidation used to coerce women, mostly right off the boat from Europe, into prostitution, was an especially serious problem on the Lower East Side, where dozens, perhaps hundreds, of brothels thrived, catering to lonely immigrants separated from their families. Bronstyn, who was affectionately known to his co-workers as “the rabbi,” headed up a small unit dedicated to saving women from prostitution.

This was of interest to my father, who, as a young reporter eager to make a name for himself, was always on the lookout for a good story. He wrote several feature stories on the white-slavery problem, and, that April, soon after Passover, he was invited along on a number of raids coordinated between Bronstyn’s agency and the police on brothels believed to be holding Jewish women against their will. His stories about these raids, accompanied by photographs, were splashed across the front page of the usually restrained

Day

and caused a sensation throughout the Lower East Side and the city in general, where the Jewish community had preferred to look the other way. A story my father wrote, based on interviews with some of the freed women, and headlined “Someone’s daughters,” was especially controversial, and was a feather in his cap. He was grateful to Bronstyn for having steered him to these stories and helped him get them, while Bronstyn, in turn, was grateful to my father for publicizing the problem and his agency’s efforts.