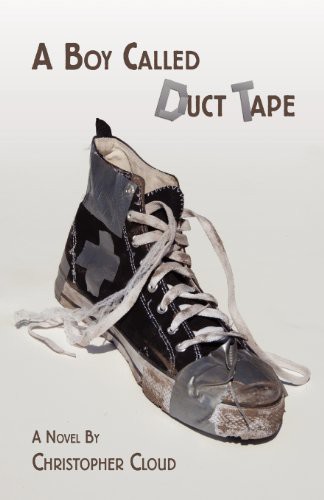

A Boy Called Duct Tape

Read A Boy Called Duct Tape Online

Authors: Christopher Cloud

Tags: #Fiction, #Suspense, #Action & Adventure, #Thrillers

By Christopher Cloud

To My Mother and Father

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious.

Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

or to just say “Hi” to Christopher Cloud:

[email protected]

Cover Design: Dana Sullivan

Photography: Bruce Watkins

Copyright © 2012 by Ron Hutchison

All Rights Reserved

Digital Editions (epub and mobi formats) produced by

Booknook.biz

1

I thought I was drowning.

I was ten feet below the surface of the water and I was out of air. Totally. My lungs were screaming at me to suck in a big breath, and the muscles in my arms and legs were on fire. Pushing through the pain and the fear, I kicked and clawed at the water like a drowning rat. I expected my heart to explode.

I didn’t remember Harper’s Hole being this deep.

A headline in the

Jamesville Times

flashed before my eyes:

LOCAL BOY, 12, DROWNS IN JAMES CREEK

I was hoping that if I did drown, Mom would bury me along side Dad in James Cemetery, a tidy patch of green overlooking the creek. Maybe Father Ramos from our church could say a prayer or two. (Thinking about my Dad made me sad. I don’t know how I could have been thinking about my Dad because I was drowning, but I did.)

I could see the splinters of sunlight glimmering on the surface of the creek above—I was only a measly breaststroke away from reaching it—when my brain flashed an urgent order:

Breathe

!

Now

! But I couldn’t. If I did, my lungs would fill with water and I would sink like a rock.

Digging savagely at the water, I tried to ignore the command from my panicked brain, but it was so overpowering that I opened my mouth and gobbled a giant breath at the exact instant I broke through to the surface.

Air!

I gasped, drew a second mighty swallow of air, and then gasped again. Whew! It was close, but I had not drowned after all, and I lifted my fist in victory. In my fist was a reddish-brown stone I had found on the bottom. It was flat on both sides. A skipper.

“Got one, Pia!” I shouted to my sister, who stood watching wide-eyed on the riverbank above.

“Awesome!” Pia cried, pushing a tangle of hair away from the grin on her toast-brown face. She was about to burst. “Now skip it, Pablo!”

With a practiced flick of my wrist, I skipped the stone across the shining face of James Creek. The stone danced over the water and onto a batch of rocks jutting out from the base of Bear Mountain.

“Now it’s my turn!” Pia squealed.

“It’s too deep, Pia,” I warned, shaking my head. “I barely made it.”

“Maybe it’s too deep for you, but not for me,” my sister boasted, peering into the pool of water.

This was Pia’s first trip to Harper’s Hole. Our mother had forbidden Pia from swimming there with me until she was nine. Pia turned nine last month.

“I can see the bottom from here,” Pia noted, peeking over the embankment and giving the deep hole a second look. Slivers of sunlight reflected off the surface of the water like pea-sized diamonds. “It’s not that deep.”

“I’m telling you, Pia, it’s deeper than it looks.”

“I’m a good swimmer,” Pia insisted. “In fact, I bet I’m a lot better swimmer than you were when you were my age.” Pia had taken swimming lessons the summer before at the Jamesville city pool.

I gave a big sigh. I could see that it was going to be a long and complicated argument. I said, “What happens if you can’t hold your breath?”

“So what?” Pia said. “I’ll just turn around and swim back to the top.”

“Okay, but what happens if you swallow a bunch of water? You could get choked.”

Pia had an answer for everything. “I won’t swallow any water if I keep my mouth shut.”

“Yeah, but what happens if you get dizzy and pass out?”

Pia frowned. “Pass out?”

I had finally gotten her attention.

“Yeah, like going unconscious,” I said, trying to sound serious. “You could drown.”

“If I get dizzy and go unconscious”—she had mangled the word

unconscious

—“you can dive down and save me.”

I didn’t say anything. I was fresh out of reasons why Pia shouldn’t try swimming to the bottom of Harper’s Hole.

Pia took a step closer to the steep riverbank and gave the deep hole a final inspection. “Is the water cold?”

Was that doubt I heard in her voice?

“Yeah, it’s cold at first, but the cold doesn’t last long,” I said, “I was cold before, but not now.”

“Are you warm?”

“No, but I’m not cold, either.”

Pia blew out a puff of air and slipped out of her flip flops. “You promise to save me if I go unconscious?” She mangled the word again.

“Yeah, I promise,” I pledged, treading water in the middle of the creek.

Pia stepped over to the cottonwood tree and wrapped her fingers around the tattered rope hanging from one of the thick upper branches. Hitching up one sagging strap of her polka-dot bathing suit, rope in hand, she took four giant steps backward, paused, took four giants steps forward—she was back where she started—and then paused again.

“Pablo, how long will it take to get used to the cold water?”

“Maybe a minute.”

Pia raised her hand and shaded her eyes from the sun, then gazed up at the limb holding the rope. She tugged on the rope to test its strength.

I watched quietly as my sister gathered her courage. I could tell from the way Pia was chewing on the knuckle of her thumb that she was having second thoughts.

A dragonfly sailed past and I splashed water at it.

“Are there any of those hungry fish down there?” Pia asked.

I groaned. “What the heck are you talking about?” Pia was testing my patience, which was typical.

“Those fish we saw on television. The ones that eat people.”

“Pia,” I said, fighting the urge to laugh, “are you going to jump in or not?”

My sister stood motionless waiting for an answer. Still grasping the rope, she folded her arms across her chest. I’d seen that look before. We were at a stalemate.

I rolled my eyes and said, “Do you actually think I’d be swimming in this river if there were piranhas? There aren’t any piranhas within a thousand miles of Harper’s—”

I left the thought dangling in the air because the traffic light inside Pia’s head had finally turned green and she had shoved the pedal all the way to the floor. Holding tight to the frayed rope, she made a hobbled dash for the river. When she reached the edge of the steep clay embankment her feet left the ground and she swung out over the water like some circus performer. Pia uttered a loud, terrified scream, released her grip, and dropped with a loud splash in the middle of the stream.

It was May and James Creek was as cold as winter ice.

Pia popped to the surface like a human cork—a frozen human cork. Her eyes had doubled in size and she struggled to draw a full breath. “COLD!” she shrieked.

I had never seen my sister’s eyes so wide. She had frog eyes, and the pained look on her face was nothing short of hilarious. I couldn’t help myself and I threw back my head with a burst of laughter.

“STOP LAUGHING!” Pia howled.

I hadn’t meant to make light of my sister’s suffering—the sudden chill of James Creek had been just as agonizing for me—and I trapped another laugh-bubble with my hand, and then said, “It’s not cold for very long. Like I said, maybe a minute.” I swam over to her and in a comforting voice said, “Less than a minute now. Maybe 45 seconds.” I felt guilty for laughing.

“P-P-Promise?” Pia was blinking like a lizard.

“Yeah, I promise. Now maybe 30 seconds.”

“C-C-Cold!” Pia’s teeth were chattering.

A man’s voice caused us to look up. “Coming through!”

Three shiny aluminum canoes approached. JAMESVILLE RIVER TOURS was painted on the side of each canoe. A bearded man in blue-jean cutoffs and a Dallas Cowboys ball cap was sitting in the first canoe. His T-shirt read:

I’d Rather Be Fishing

.

The two trailing canoes were each occupied by a man and a woman in swimming suits. Their skin as red as lobsters, they were drinking beer. One of the men was wearing a white visor. He was laughing so hard at something his fat friend in the other canoe had said that he almost tipped his own canoe. It was wobbling so much I thought it might tip.

“Morning, kids!” the bearded man called out.

Pia and I returned the greeting.

“You two be real careful swimming,” the bearded man cautioned, gesturing at the water with his paddle. “Harper’s Hole. She’s plenty deep. You be real careful.”

“We will,” I said. “I’ve swam here before.”

“My brother’s a famous BMX stunt rider!” Pia shouted, a smile stretching her purplish lips. “He’s going to try out for the Olympics when he gets older!” She’d forgotten all about being cold.

“Pia …” I said, mortified.

“Well, now,” the bearded man said, “we have a celebrity in our midst.” Pulling his paddle gently through the water, his canoe drew up to us.

“I’m not

that

famous,” I said. “I placed first in a Best Trick contest in Joplin last week.”

“He can do a 360 double tailwhip!” Pia gushed. “It’s awesome!”

“Okay, Pia. Zip it.”

“He won a new Mongoose dirt bike and gave me his old one!” She pointed at our dirt bikes leaning against the big cottonwood tree.

“Pia!”

“Now I’d call that brotherly love,” the bearded man said, talking over his shoulder.

After the canoes had passed, I said, “That’s what I want to do someday. Work as a river guide.” I watched the canoes disappear around a bend.

Pia looked at me like I’d lost my mind. “Huh? I thought you wanted to be a famous BMX stunt rider.”

“I can do both.”

Pia paused. She was working out something in her head. “Can girls work as river guides?”

“Sure. Why not?”

Pia considered my answer for a moment, and said, “Then I want to be a river guide, too.”

And with that, Pia drew a big breath of air, ducked below the surface of James Creek, and began swimming toward the bottom of Harper’s Hole, her thin little arms and one good leg thrashing the water.

I watched my sister’s flickering image for any signs of trouble.

I had recovered my first stone from the bottom of Harper’s Hole the summer before, when I was 11. Not only had I pried a colorful stone from the watery floor of James Creek, but I had discovered an underground spring that fed into Harper’s Hole from the base of Bear Mountain. That’s why the deep hole was so cold. It was spring-fed.

That’s deep enough, Pia,

I told myself as I watched my sister’s progress … or lack of progress. She was no more than five feet below the surface of the water. Pia’s bad leg was throwing her off course, and she was going more sideways than down.

Harper’s Hole was a special swimming place revealed to us by our father the same year he died, three years earlier. The swimming hole was located at the end of an old animal trail not far from Jamesville. People said bears roamed the woods, but I had never seen one.

Pia popped to the surface.

“It’s too deep, Pablo!” she cried, gasping for air. “I can’t hold my breath …”

“I told you it was deep,” I reminded my sister.

Pia’s plum-colored lips began to quiver. “Now I’ll never get … get a skipper.” Her dark eyes turned misty.

“Sure you will.”

“How?”

“I’ll get one for you.”

“Promise?” she asked in a choked voice.

I nodded. “Promise.”

“A skipper?” Her teary eyes began to shine.

“Yeah, a skipper.”

I flashed Pia a grin, sucked in an enormous breath of air, then dived toward the bottom. I could see the hollowed-out riverbed in the clear, cold waters of James Creek. The afternoon sunlight reflected a rainbow of bright colors off its pebbled face, and it seemed like a person could reach out and touch the bottom. It looked close. But I knew better. It wasn’t close. It was deep—nearly 20 feet. One of the deepest holes in James Creek.

Halfway down, my lungs began to burn, just as they had on my earlier dive, and a desperate urge to return to the surface pounded away inside my head. But I pushed the thought of quitting out of my mind—this dive was for Pia—and I swam deeper, releasing all my air in a bubbled spurt.

A sunfish darted past.

I was deep now, so deep that I could feel the icy current of spring water gushing from the wide gash in the side of Bear Mountain. Another few feet and I would snatch up my prize. I had already spotted it amongst the colorful stones that were lying like a blanket of jewels on the palm-shaped river bottom. The stone was bright gold.