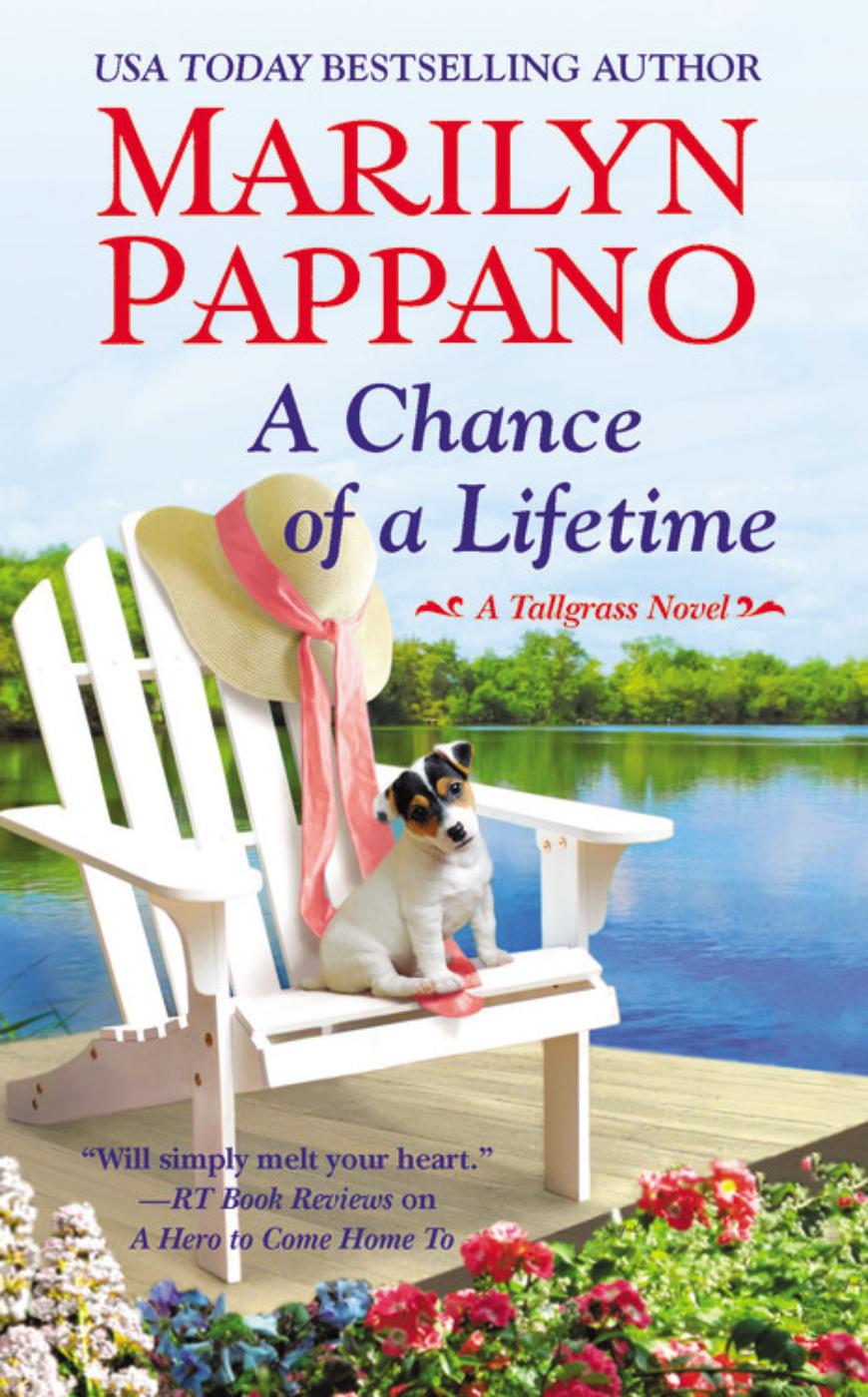

A Chance of a Lifetime

Read A Chance of a Lifetime Online

Authors: Marilyn Pappano

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author's intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author's rights.

For all the combat medics and corpsmen who rush into danger to save not just their buddies but anyone who needs their help. You guys are the bravest, the toughest, the heroes responsible for giving a second chance at life to so many of our troops.

Â

And as always, for my favorite “Devil Doc,” my husband, Robert. Your Marines and I are lucky to have you!

The soldier, above all other people, prays for peace, for he must suffer and bear the deepest wounds and scars of war.

âGeneral Douglas MacArthur

It has been said, “time heals all wounds.” I do not agree. The wounds remain. In time, the mind, protecting its sanity, covers them with scar tissue and the pain lessens. But they are never gone.

âRose Kennedy

Y

ou can't go home again,

someone had famously said.

Someone else had added,

But that's okay, because you can't ever really leave home in the first place.

Calvin Sweet was home. If he tried real hard, he could close his eyes and recall every building lining the blocks, the sound of the afternoon train, the smells coming from the restaurants. He could recognize the feel of the sun on his face, the breeze blowing across his skin, the very scent of the air he breathed. It smelled of prairie and woodland and livestock and sandstone and oil and history and home.

There were times he'd wanted to be here so badly that he'd grieved for it. Times he'd thought he would never see it again. Times he'd wanted never to see itâor anything elseâagain. Ironically enough, it was trying to ensure that he would never come back except in a box that had brought him home, alive and unwell.

He didn't close his eyes. Didn't need a moment to take it all in. Didn't want to see reminders of the streets where he'd grown up, where he'd laughed and played and lived and learned with an innocence that was difficult to remember. He just stared out the windows, letting nothing register but disquiet. Shame. Bone-deep weariness. It wasn't that he didn't want to be in Tallgrass. He didn't want to be anywhere.

“You have family in the area,” the driver said, glancing his way.

It was the first time the corporal had spoken in twenty miles. He'd tried to start a couple of conversations at the airport in Tulsa and in the first half of the trip, but Calvin hadn't had anything to say. He still didn't, but he dredged up a response. “Yeah. Right here in town.”

When the Army sent troops to the Warrior Transition Units, they tried to send them to the one closest to home so the family could be part of the soldier's recovery. Calvin's mama, his daddy, his grandma and aunties and uncles and cousinsâthey were all dedicated to being there for him. Whether he wanted them or not.

“How long you been away?”

“Eleven years.” Sometimes it seemed impossible that it could have been so long. He remembered being ten and fourteen and eighteen like it was just weeks ago. Riding his bike with J'Myel and Bennie. Going fishing. Dressing up in a white shirt and trousers every Sunday for churchâblack in winter, khaki in summer. Playing baseball and basketball. Going to the drive-in movie, graduating from elementary school to middle school to high school with J'Myel and Bennie. The Three Musketeers. The Three Stooges.

The best memories of his life. He'd never thought it possible that

All for one and one for all!

could become

two against one

, then

one and one

. J'Myel had turned against him. Had married Bennie. Had gotten his own damn self killed. He hadn't spoken to Calvin for three years before he died, and Bennie, forced to choose, had cut him off, too. He hadn't been invited to the wedding. Hadn't been welcome at the funeral.

With a grimace, he rubbed the ache in his forehead. Remembering hurt. If the docs could give him a magic pill that wiped his memory clean, he'd take it. All the good memories in his head weren't worth even one of the bad ones.

At the last stoplight on the way out of town, the corporal shifted into the left lane, then turned onto the road that led to the main gates of Fort Murphy. Sandstone arches stood on each side, as impressive now as they'd been when he was a little kid outside looking in. Just past the guard shack stood a statue of the post's namesake, Audie Murphy, the embodiment of two things Oklahomans valued greatly: cowboys and war heroes. Despite being scrawny black kids and not knowing a damn thing about horses, he and J'Myel had wanted to be Audie when they grew up.

At least they'd managed the war hero part, according to the awards they'd been given. They'd both earned a chestful of them on their tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

With a deep breath, he fixed his gaze outside the windows, forcing himself to concentrate on nothing that wasn't right there in front of him. They were passing a housing area now, the houses cookie cutter in size and floor plan, the lawns neatly mowed and yellowed now. October, and already Oklahoma had had two snows, with another predicted in the next few days. Most of the trees still bore their autumn leaves, though, in vivid reds and yellows and rusts and golds, and yellow and purple pansies bloomed in the beds marking the entrances to each neighborhood.

They passed signs for the gym, the commissary, the exchange, barracks and offices, and the Warrior Transition Unit. Their destination was the hospital, where he would be checked in and checked out to make sure nothing had changed since he'd left the hospital at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington that morning. He tried to figure out how he felt about leaving there, about coming hereâpsychiatrists were big on feelingsâbut the truth was, he didn't care one way or the other.

His career was pretty much over. No matter how good a soldier he'd been, the Army didn't have a lot of use for a captain who'd tried to kill himself. They'd diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder, the most common injury suffered by military personnel in the war on terror, and they'd started him in counseling while arranging a transfer to Fort Murphy. Soon he would be separated from the Army, but they would make a stab at putting him back together before they let him go.

But when some things were broken, they stayed broken. Nothing could change that.

Within an hour, Calvin was settled in his room. He hated the way people had looked at his medical record, hated the way they'd looked at him.

He's a nut job, a weak one. Killed the enemy in the war but couldn't even manage to kill himself. What a loser.

More likely, those were his thoughts, not the staff's.

He sat on the bed, then slowly lay back. He could function on virtually no sleepâhe'd done it too many times to countâbut sometimes his body craved it. Not in the normal way, not eight or nine hours a night, but twenty-hour stretches of near unconsciousness. It was his brain's way of shutting down, he guessed, of keeping away things he couldn't deal with. He could go to sleep right now, but it wouldn't last long, because his parents were coming to see him, and Elizabeth Sweet wouldn't let a little thing like sleep deter her from hugging and kissing her only son.

Slowly he sat up again. His hands shook at the thought of facing his parents, and his gut tightened. Elizabeth and Justice hadn't raised a coward. They'd taught him to honor God, country, and family, to stand up for himself and others, to be strong and capable, and he'd failed. He'd tried to kill himself. He knew that sentence was repeating endlessly, disbelievingly, not just in his head but also in theirs.

He was ashamed of himself for such poor planning. He'd never once seen anyone at that public park in all the times he'd been there, and he certainly hadn't counted on some misguided punk to intervene. After “saving” Calvin's life, the kid, named Diez, had stolen his wallet and car and disappeared. Some people got the Good Samaritan. He got the thieving one.

Announcements sounded over the intercom, calling staff here or there, and footsteps moved quickly up and down the hall, checking patients. Calvin sat in the bed and listened, hearing everything and nothing, screening out all the extraneous noises until he heard the one he was listening for: the slow, heavy tread of his father's work-booted feet. Justice had a limpâarthritis in knees punished by years laying floor tileâand the resulting imbalance in his steps was as familiar to Calvin as his father's voice.

The steps stopped outside his door. Calvin's heart pounded in his chest, so he took a deep breath to slow it, to prepare himself, and imagined his parents doing the same. He slid to his feet as the door slowly swung open and his mom and dad just as slowly came inside. For a moment, they stared at him, and he stared back, until Elizabeth gave a cry and rushed across the room to wrap her arms around him.

She was shorter, rounder, and he had to duck his head to rest his cheek against her head, but he felt just as small and vulnerable as he ever had. There'd never been a thing in his life that Mom couldn't make better with a hugâuntil nowâand that just about broke his heart.

It seemed forever before she lifted her head and released him enough to get a good look at him. Tears glistened in her eyes, and her smile wobbled as she cupped her hand to his jaw. “Oh, son, it's good to see you.” Her gaze met his, darted away, then came back with a feeble attempt at humor. “Or would you prefer that I call you sweet baby boy of mine?”

He managed to phony up a smile, or at least a loosening of his facial muscles, at the memory of her response when he'd complained about being called

son

in front of his friends. “Son is fine.” His voice was gravelly, his throat tight.

“You know, I can come up with something even worse.” But there was no promise behind her words, none of that smart mouth that she lived up to quite nicely most of the time. She was shooting for normal, but he and she could both see there was nothing normal about this situation. He hadn't known normal for so long that he was wearied by it.

Justice stepped forward. “Move on over a bit, Lizzie. Let a man give his only boy a welcome-home hug.” His voice was gravelly, too, but it always had been, rough-edged and perfect for booming out

Amen

s in church or controlling small boys with no more than a sharp-edged word.

Elizabeth stepped aside, and Justice took his turn. His hug was strong and enveloping and smelled of fabric softener and the musky aftershave he'd worn longer than Calvin had been alive. It was so familiar, one of those memories that never faded, and it reminded Calvin of the person he used to be, the one who could do anything, be anything, survive anything, and prosper.

The one who had disappointed the hell out of his mother, his father, and himself.

After his dad released him, they all stared at each other again. Calvin had never seen them looking so uncomfortable, shifting their weight, wanting to smile but not sure they should or could. The psychiatrist in Washington had tried to prepare him for this initial meeting, for the embarrassment and awkwardness and guilt. For no one knowing what to say or how to say it. For the need to be honest and open and accepting and forgiving.

Calvin had been too lost in his miseryâand too angry at Diezâto pay attention.

Should he point out the elephant sitting in the middle of the room? Just set his parents down and blurt it out?

Sorry, Mom and Dad, I tried to kill myself, but it wasn't you, it was me, all my fault. Sorry for any distress I caused. Now that we've talked about it, we don't ever need to do it again. Soâ¦how's that high school football coach working out?

And as an aside:

Oh, yeahâ¦I'm getting help and I haven't tried anything since. We're cool, right?

Unlessâhis gut tightenedâhe did try again. He didn't want to, swore he didn't, but the fear haunted him: that the docs would help, the meds would help, he'd find a reason to live, and then something in his screwed-up brain would put a gun in his hand again.

His throat worked hard on a swallow, his jaw muscles clenched, and his stomach was tossing about like a leaf in a storm, but he managed to force air into his lungs, to force words out of his mouth. “Soâ¦it was cold outside when I got here.”

“Dropped to about thirty-eight degrees.” There was relief in Justice's voice for a conversation he could embrace. “Wind chill's down in the twenties. The weather guys are saying an early winter and a hard one.”

“What's Gran say?”

Elizabeth's smile was shaky. “She says every winter's hard when you're seventy-six and have the arthritis in your joints.”

“She wanted to come with us, but⦔ Justice finished with a wave of his hands. “You know Emmeline.”

That Calvin did. Emmeline would have cried. Would have knelt on the cold tile and said a prayer of homecoming. Would have demanded he bend so she could give him a proper hug, and then she would have grabbed his ear in her tightest grip and asked him what in tarnation he'd been thinking. She would have reminded him of all the switchings she'd given him and would have promised to snatch his hair right out of his scalp if he ever even thought about such a wasteful thing again.

He loved her. He wanted to see her. But gratitude washed over him that it didn't have to be tonight.

“Your auntie Sarah was asking after you,” Elizabeth said. “She and her boys are coming up from Oklahoma City for Thanksgiving. Hannah and her family's coming from Norman, and Auntie Mae said all three of her kids would be here, plus her nine grandbabies. They're all just so anxious to see you.”

Calvin hoped he was keeping his face pleasantly blank, but a glimpse of his reflection in the window proved otherwise. He looked like his eyes might just pop out of his head. He'd known he would see familyâmore than he wanted and more quickly than he wantedâbut Thanksgiving was only a month away. Way too soon for a family reunion.

His mother went on, still naming names, adding the special potluck dishes various relatives were known for, throwing in a few tidbits about marriages and divorces and new babies, talking faster and cheerier until Justice laid his hand over hers just as her voice ran out of steam. “I don't think he needs to hear about all that right now. You know, it took me a long time to build up the courageâ” His gaze flashed to Calvin's, then away. “To get used to your family. All those people, all that noise. Calvin's been away awhile. He might need some time to adjust to being back before you spring that three-ring circus on him.”

Elizabeth's face darkened with discomfort. “Of course. I mean, it's a month off. And it'll be at Auntie Mae's house so there will be plenty of places to get away for a while. Whatever you want, son, that's what we'll do.”