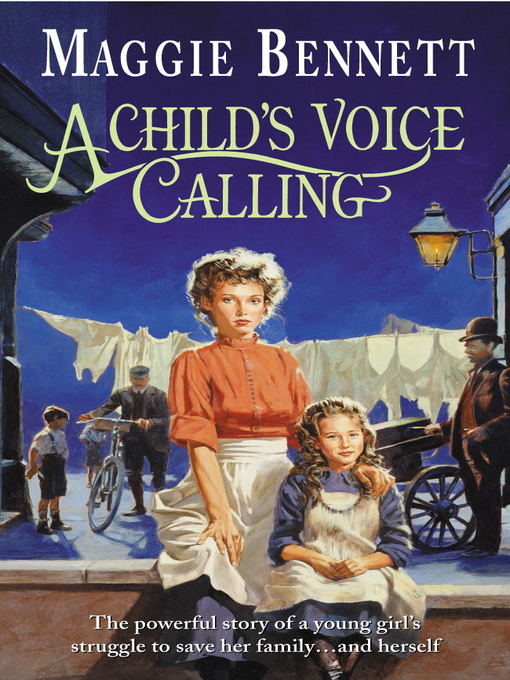

A Child's Voice Calling

Read A Child's Voice Calling Online

Authors: Maggie Bennett

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary, #Genre Fiction, #Family Saga, #Contemporary Fiction, #Literary, #Romance, #Sagas, #Historical Saga

Contents

Young Mabel Court, child of her mother's hasty marriage to a spendthrift, becomes 'little mother' to her brothers and sisters growing up in south London at the start of the twentieth century.

With poverty never far from the door, the battle to stay respectable is finally lost when the family breaks up in tragic circumstances, and Mabel is thrown upon the dubious mercy of her grandmother, the sinister Mimi Court, who has her own dark secrets.

But faithful Harry Drover of the Salvation Army, in love with Mabel, gets an opportunity to prove his devotion when Mimi falls foul of the law and Mabel has to fight for her own survival . . .

Maggie Bennett was born in Hampshire. When she left school at eighteen she started general nursing training and, after a year as a staff nurse, she went on to train as a midwife. Her career was interrupted by marriage at thirty-five, and she moved to Manchester where her two daughters were born; she later returned to work as a midwife until her retirement in 1991. Having been an avid reader and scribbler all her life, she took a correspondence course in creative writing after her husband’s death in 1983, and started writing articles and short stories.

A Child’s Voice Calling

is her first novel.

Maggie Bennett

In loving and respectful memory of my aunt

MABEL ANNA COATES

(1891–1979)

And with grateful acknowledgement to

Judith Murdoch, literary agent.

ANNA

-

MARIA’S FIRST BABY

was conceived in a golden Hampshire meadow beneath a hedgerow of tumbling wild roses, in an ecstasy of loving and giving; the confinement took place at 23 Macaulay Road, Tooting and she was completely at the mercy of her mother-in-law.

Mrs Court stood over her, arms akimbo, sleeves rolled up to her elbows. ‘Ye’ve got a fair way to go yet, Annie. The head’s still high, so ye’d best get up off that bed and walk around for a bit, to bring it down.’

The girl winced as another contraction began, tightening her abdomen to board-like hardness. Surely this could get no worse!

‘Come on, ye’ll do no good lyin’ there, my girl, get up an’ take a turn round the room. Yer can lean over the bed rail when yer get a pain, an’ breathe hard in an’ out.’

Anna-Maria had to obey, as she had done ever since she’d met Jack’s mother. Ever since she’d run away from her home, broken her father’s heart and estranged herself from her sisters. Ever since she’d jilted young Eric Drummond who’d told her he loved her. Only last summer, but a lifetime away.

‘Sit down by the window for a bit, an’ get a breath of air,’ said Mimi Court, pushing up the sash an inch or two. ‘Nobody’ll see yer through the net curtain.

I’ll get Elsie to bring a cup o’ tea – be back in a minute.’

Anna-Maria sat down heavily and looked out on Macaulay Road. Oh, how she had hoped and longed and prayed to be out of this house and into a home of her own before the confinement! It was almost seven months since Jack had first brought her here after their elopement and her thoughts went back to that September afternoon.

It had all been so romantic, her first sight of London: the River Thames and Westminster Abbey, the Houses of Parliament and the big clock, just as in the pictures she had seen. She and her beloved Jack had mixed with the fashionable throng in St James’s Park, the gentlemen in pearl-grey top hats escorting ladies bedecked and beribboned in silk and lace, topped with enormous feathered hats and carrying dainty parasols.

But then they had to get a motor-bus, something Anna-Maria had never seen before, and travel down to Clapham, where they boarded another bus, this time a horse-drawn one which set them down beside a large stretch of common land. Jack paid threepence to a man who carried his portmanteau on a handcart down a wide, unpaved lane with trees on either side, turning right into Macaulay Road. Number 23 was one of a row of solid gabled terraced houses with small front gardens bounded by privet hedges and iron railings.

Jack had told her that his widowed mother was a midwife and also took in lodgers, so Anna-Maria pictured a woman who was kind and hard-working. Nevertheless she felt increasingly apprehensive as the meeting approached and hung back when Jack inserted his key into the front door.

‘Here we are, sweetheart. Yer mustn’t mind me mother, she’s bound to be a bit surprised at first.’ He opened the door and called out. ‘Helloo-oo! I’m home again!’

Anna-Maria put on a demure smile to greet Mrs Court.

The figure of a woman appeared in the passage. She was in her early forties, short and round-bodied, not fat, and wore a gown in a deep plum colour, buttoned up to the neck and lace-trimmed. As she stepped forward Anna saw sharp brown eyes and a jutting nose like Jack’s, though her colouring was much less dark. Her hair was styled like the Queen’s, drawn smoothly to the back of her head where a short length of fine black lace fell to her shoulders. For one brief moment she stared at Anna-Maria who involuntarily drew back.

‘Mimi!’ cried Jack, holding out his arms.

Mimi? Was this a pet name like mamma?

The woman smiled and allowed Jack to embrace her. ‘And about time, yer young rascal. What’re yer been up to?’ She looked past him at Anna-Maria. ‘Yer didn’t say yer was bringing company.’

Her way of speaking resembled Jack’s, though she made an attempt at superiority, carefully sounding her aitches and drawling over the vowels; this was her company voice and likely to be completely discarded in times of anger or emotion, as Anna-Maria soon discovered. ‘And who is this young lady?’

‘This is Miss Anna-Maria Chalcott and I’ve brought her back with me from Belhampton,’ answered Jack with just a slight hesitation. ‘Miss Chalcott, this is my mother.’

Anna-Maria gave a slight bow and was about to

say ‘How do you do?’ when the woman forestalled her: ‘Why, Miss Chalcott, what was yer parents thinkin’ of, lettin’ yer leave yer home in the country?’

Anna-Maria looked to Jack for aid and he hastily answered on her behalf: ‘Miss Chalcott’ll write to her father and let him know she’s safe and well. Meanwhile she can stay here, can’t she, Mimi? She can have my room.’

‘Not with you in it, she can’t, whatever next? My goodness me!’ Mrs Court sounded very shocked. ‘Ye’ll have to stay at Bill Williamson’s down the road. Anyway, ye’d better come in.’

Jack stood aside to let Anna-Maria follow his mother into an over-furnished living room where she was told to take a seat. Mrs Court went through to a kitchen beyond, beckoning Jack to follow her. Although the door was shut, Anna-Maria picked up some of their heated exchange.

‘I tell yer, Mimi, I’m not askin’ yer to do anythin’! As far as I know she’s not even—’

‘But she could be, yer mean? Once is enough, think o’ that Hackney girl.’

‘An’ anyway, it don’t signify because I love her, if yer can understand that, an’ I’ve said I’ll marry her.’

While unable to hear much of what was said, Anna-Maria heard

that

, spoken boldly by the man she adored, and she sighed in sheer relief. Dearest Jack!

Mrs Court was speaking again: ‘The mother’s dead, yer say. Any money there?’

Jack muttered something about a nice line in draperies and upholstery, a big house and a decent little two-wheeled gig.

‘Oh, tradespeople. Nothin’ to give herself airs

about. And no son to take the lot when the father goes?’

Anna-Maria closed her eyes, suddenly tired and feeling slightly sick. A few minutes later Mimi bustled in with a tray of tea and cake. Jack followed with a hot-water jug and winked at Anna-Maria from behind his mother’s back as she put down the tray.

‘A cup of tea, thank you, that’s all, Mrs Court,’ said Anna-Maria quickly, conscious of those sharp eyes upon her, and longing to be alone with Jack.

But that was not allowed her, not for a whole week, during which Jack slept at a neighbour’s house and met her only in the company of his mother and when he took her out for walks and to the Sunday morning service at St Nicholas’s church. This was followed by a lavish dinner at which Mimi Court presided and carved the joint.

There seemed to be two permanent lodgers, a thin, worried-looking woman called Miss Lawton who went out to give piano lessons and her elderly mother who seldom emerged from the room they shared.

‘The ol’ girl’s lost her wits and don’t know what day it is or where she is,’ Jack explained. ‘Mimi took ’em in because they’d lost their home and were almost starvin’ – she’s got a good heart that way, y’know. Some o’ Mimi’s patients stay here for a while, like that one.’

He nodded towards a heavily pregnant young woman called Ivy who sat down with them to Sunday dinner and hardly uttered a word.

Elsie was a sullen maidservant who seemed to occupy a special position in the house, though it took Anna-Maria some time to discover what it was.

Under Jack’s guidance – and he was under his mother’s – Anna-Maria wrote a deeply penitent letter to her father, begging him to forgive her for running away, and telling him that she was happy and comfortable at the home of Mr Court’s mother until they could be married and have a home of their own. She sent her love to her sisters Kate and Nell, and said she looked forward to visiting Belhampton again as Mrs Court, accompanied by her dear husband who also sent his deepest respects and kindest regards.

A whole week passed with no reply, then came a black-bordered envelope from Miss Chalcott, the eldest sister. It was short, cold and carried dreadful news. There was to be no happy return for the prodigal daughter. For George Chalcott had suffered a severe seizure while returning home in the gig and in spite of the best medical attention had died without regaining consciousness. ‘You have brought shame and disgrace upon our family, and the shock has killed our poor father,’ Katherine had written. ‘Your presence at his funeral service or at this house will not be welcome, and neither Elinor nor I ever wish to see you again.’

Mrs Court found Anna-Maria lying on the floor where she had fainted and a doctor was sent for. He confirmed what Mimi already suspected, that a child was expected in the following spring, about the beginning of April. A quiet wedding was hastily arranged at St Nicholas’s church between Miss Anna-Maria Chalcott and Mr John Masood Court.

Thankfully back in his own bed, Jack’s eager anticipation of his wedding night received a setback when his young wife wept uncontrollably in his arms. ‘Papa, oh, dearest papa, forgive me!’ she

sobbed over and over again, until at last she fell into an exhausted sleep.

Which left Jack no choice but to turn over and fall asleep also.

When a letter arrived from the Chalcotts’ family solicitor with the news that there was no bequest for Anna-Maria, at least not for the time being, Court’s brow darkened. Chalcott Draperies was to stay in the family with a manager in charge and George Chalcott’s capital, mostly invested in bonded stock, was to be transferred to his daughters’ names in equal shares and not to be withdrawn by one of them without the consent of the other two.

‘They’re tryin’ to do us out o’ what’s ours by law,’ Jack muttered angrily to his mother. ‘I’ve a good mind to go and confront that crook of a lawyer meself.’

But Mimi counselled patience. ‘Could be all for the best,’ she said with a knowing nod. ‘The longer it’s left the more it’ll grow.

And

it can’t be squandered, neither.’

Soon after this Jack took his portmanteau packed with haberdashery samples and the photographic equipment that was his sideline, and went off on another business expedition, leaving his new wife to be taken in hand by his mother.

‘Ye’ll have to learn to pull yer weight, my girl,’ Mimi declared on finding Anna-Maria still in bed at nine. ‘I can tell ye’ve always had it easy, what with bein’ the youngest and yer pa’s pet an’ all, but cryin’ won’t bring him back, neither will layin’ around bein’ waited on.’ Tying a long white apron over Anna-Maria’s black mourning dress, she added

briskly, ‘Ye’re a married woman now and ye’ll have to learn how to keep house for my son. Now, then!’

Dazed by the changes that had overtaken her, Anna-Maria obeyed with a docility that would have astonished her sisters. The child growing within her seemed to have taken over her mind as well as her body and half the time she seemed in a dream. Under Mimi’s supervision she prepared vegetables, grated suet for puddings, washed fruit for cakes, kneaded dough, trimmed meat and fish for roasting and baking. Her hands roughened and she was often extremely tired, but at least she had no time to mope under the burden of sorrow and guilt that Kate’s letter had laid upon her.