A Complicated Marriage (17 page)

Read A Complicated Marriage Online

Authors: Janice Van Horne

Â

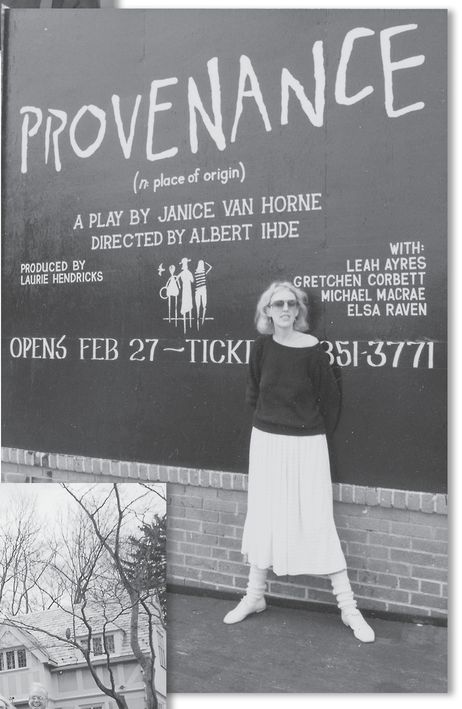

The playwright poses for an L.A. production, 1989.

Â

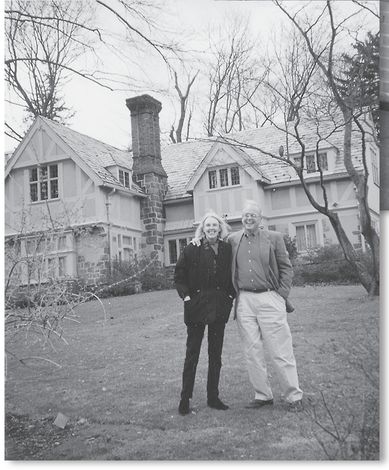

The “kids” revisit Green Haven, 1996.

Â

Our last photo, outside the Pollock house, 1992.

(Photograph by Elaine Grove)

part two

Artists & Wives & a Trip

HANS AND MIZ HOFMANN

IT WAS LATE Friday afternoon of Labor Day weekend in 1957 when I passed for the first time through the front gate of Hans and Miz's house in Provincetown. As usual, when venturing off with Clem, I had no idea what to expect.

We had come a long way. The Cape Codder train to Woods Hole, then the long bus ride to the farthest tip of Cape Cod, and finally a taxi to the Hofmanns' house near the end of Commercial Street, the town's main drag. At first sight, it was like no artist's house I could have imaginedâa white colonial fronted by a picket fence with a brick path that invited us to the front door through a garden ablaze with flowers. But then we crossed the threshold. I thought I had stepped into Hofmann's body and soul. The floors, the furniture, the stairs, everything, painted in his signature vibrant, primary colors. A high-gloss Technicolor toyland. Upstairs, in the large square guest room, the same. Here the late-afternoon light bounced off the sea and danced with the rainbow colors of the room. Never before had I been in a place that made me so happy to be alive.

The Hofmanns had spent twenty years of summers there by that time. There was an inherent stability in that house such as I had never known. My family had never lived anywhere longer than a few years. From place to place we carted our things, shedding bits and pieces along the way, but we never called the walls that contained them “home.” This was a home, one of impeccable order, run by Miz with precision and love. I sensed that Miz and Hans moved through those rooms on harmonious, parallel pathsâHans also had his own path, which led from the back of the house to his studioâeach endowing their domains with complementary skill and passion.

The Hofmanns were then in their late seventies, my grandmother's

age, but there the similarity ended. That weekend I would learn that who we are is a reflection of the life we live on any given day, not the mere sum of the years we have lived. My grandmother lived the daily life of a sheltered, timid old lady and had done so for most of her life. The Hofmanns had the exuberance and self-assurance of people who knew how to enjoy life to its fullest. Each morning we were there, we would all go out to Race Point to swim in the ocean, which, thankfully, was calm enough even for me. I had never seen my grandmother swim, much less wear a bathing suit. And I had never had a grandfather. For generations the women in my family had managed at a young age to lose their husbands one way or another.

age, but there the similarity ended. That weekend I would learn that who we are is a reflection of the life we live on any given day, not the mere sum of the years we have lived. My grandmother lived the daily life of a sheltered, timid old lady and had done so for most of her life. The Hofmanns had the exuberance and self-assurance of people who knew how to enjoy life to its fullest. Each morning we were there, we would all go out to Race Point to swim in the ocean, which, thankfully, was calm enough even for me. I had never seen my grandmother swim, much less wear a bathing suit. And I had never had a grandfather. For generations the women in my family had managed at a young age to lose their husbands one way or another.

And then there was the German-ness. Again, so different from my family, who even as second-generationers still lived in an insular community and filtered their sensibilities, their views of people and the world around them, through their German-ness. The Hofmanns, in this country for only twenty-five years, kept their door always open. That weekend people streamed in and outâartists to have a chat, students to say good-bye to their teacher. The Hofmanns' accents, still dripping of Munich, had at first put my supersensitized ears on red alert. But it didn't take long to be seduced by the gemütlichkeit and Miz's cooking.

That first evening, Miz and I engaged in a long talk about food. She probably asked me whether I liked to cook and whether, having grown up with German heritage, I had any favorite foods. I would have told her that no, I had never learned to cook, that my mother didn't like to cook, and that my favorite dinner had been hot dogs, canned peas, and soggy rice. She no doubt would have noted the knockwurst connection, before adding that long-cooked rice was a wonderful German breakfast cereal, a dish she remembered fondly from her own childhood. I chimed in with my own memories of

zucker butterbrot

, a treat I loved when I was little. The next morning, there was the large pot of stewing rice on the stove. She ladled it out for me with dollops of butter and brown sugar, and, sure enough, slices of bread slathered with butter and sugar. Children together, we sat down and ate our porridge.

zucker butterbrot

, a treat I loved when I was little. The next morning, there was the large pot of stewing rice on the stove. She ladled it out for me with dollops of butter and brown sugar, and, sure enough, slices of bread slathered with butter and sugar. Children together, we sat down and ate our porridge.

Hans had an extraordinary presence. His big, round, open-as-the-sun face still shines in my mind. And his feet, in the sandals of summer, large

and square, the big toes raised up, as if ready to spring into action. For a thick-set man, his movements were unexpectedly agile and quick. There was a heat coming off him, a furnace at full blast. Even in repose, the fires burned. At times I saw him sitting alone in the backyard, plunged so deep inside himself that I wondered if he would be able to find his way back.

and square, the big toes raised up, as if ready to spring into action. For a thick-set man, his movements were unexpectedly agile and quick. There was a heat coming off him, a furnace at full blast. Even in repose, the fires burned. At times I saw him sitting alone in the backyard, plunged so deep inside himself that I wondered if he would be able to find his way back.

I had come to take for granted that artists took up all the available space and filled up the air with their single-minded passion for their work. Though I admired that passion, it didn't make them particularly accessible. Sometimes I would try to discern the difference between self-absorption, which I could understand, and coldness, which I deplored. A fine line, and often I wondered if I was misreading the two. The distinction mattered, because in those days I was concerned about whether I liked those people and, more important to me, whether they liked me.

Many times I heard artists described by women as teddy bears, usually the burly types, like David Smith, Rothko, Hofmann, and even Pollock. Let me say that I never met an artist who was a teddy bear. All too often, the heat within did not spill over into warmth toward others. Hans was a hard call. As compelling as I found his robust energy, it was tamped down by an impenetrable layer of detachment. As if he were saying,

What doesn't serve my art doesn't serve me

. On the other hand, Clem, who never, to my knowledge, had been called anything even faintly resembling a teddy bear, and despite his relentless passion for art, was an outspoken believer in life before art. And how grateful I was for it.

What doesn't serve my art doesn't serve me

. On the other hand, Clem, who never, to my knowledge, had been called anything even faintly resembling a teddy bear, and despite his relentless passion for art, was an outspoken believer in life before art. And how grateful I was for it.

Hans may have been uninterested in general conversation or, heaven forbid, small talk, but he was known as the greatest communicator. Just as his energy lit up his art and any space he was in, for his twenty-five years as a teacher it lit up all the artists who were fortunate enough to walk into his schoolyard, or be present at the renowned lectures he delivered in the late thirties. Clem had just moved into the city from Brooklyn and had begun to mix and mingle with the downtown artists. He heard some of those lectures and often spoke of the influence they had had on his perception of art. I could imagine Hans's voice, guttural and boomingâperhaps more booming by the time I met him, because by then he was quite deaf. Miz would often signal him to put in his hearing

aids, signals he would usually ignore. Around Clem, he was interested in a dialogue and he would put them in. Around many others, not so, and at parties, never.

aids, signals he would usually ignore. Around Clem, he was interested in a dialogue and he would put them in. Around many others, not so, and at parties, never.

Hans was the first and most important star in my small, though rapidly expanding, firmament of painters. He and I shared a bond no one knew about, including him. In 1955, shortly before my college graduation, he had introduced me to art.

One night my new circle of art friends commandeered me into helping them prepare for the installation of some pictures by a painter called Hans Hofmann. I didn't need coercing; I was in the middle of a brain-numbing attempt to index

Finnegan's Wake

à la Kenneth Burke, an exercise that I would soon look back on as the absurdist dead end of the modernist spiral. My friends' project would be an all-nighter in the Carriage Barn, the multipurpose arts space at that time. We unpacked the pictures, flipped them facedown, attached screw eyes and measured and strung wires, retacked stripping, and finally flipped them over again and stood them around the main floor of the barn.

Finnegan's Wake

à la Kenneth Burke, an exercise that I would soon look back on as the absurdist dead end of the modernist spiral. My friends' project would be an all-nighter in the Carriage Barn, the multipurpose arts space at that time. We unpacked the pictures, flipped them facedown, attached screw eyes and measured and strung wires, retacked stripping, and finally flipped them over again and stood them around the main floor of the barn.

Then came the good part. We broke open a quart of Mr. Boston's gin and Ritz crackers, and talked through what remained of the night. And we played with the art. Moved the paintings around. What looked good next to what, and why. And which ones we liked more than others, and why. And in the process, I looked at art for the first time. I touched the paint, the textures of art, for the first time. With Hans, I learned how to handle picturesâwith respect but not awe, carefully but not timidly. How to look at a picture separately and next to others. I learned that they had fronts and backs, that they were man-made, by someone who had something to say. And I had fun with art. Such was my night with Hans.

Now here I was two years later, sleeping in his house in Provincetown, being mothered by his wife. I hadn't attended the opening reception of that Bennington retrospective. I would have considered myself too cool for that sort of formal folderol. Hell, I would have had to brush my hair. Clem would have been there. Hans and Miz, too, no doubt. Would Clem have fallen in love with my

blauen augen

across the crowded room? Unlikely. Everything in its own time.

blauen augen

across the crowded room? Unlikely. Everything in its own time.

That weekend on the Cape we lived moment to moment. During those last days of summer, Provincetown was a moveable party town. Oh, we had our quiet times with the Hofmanns on the beach or sitting around the kitchen table. Sometimes Hans and Clem would wander off to the studio while Miz and I hung out on the porch. But other times, Clem and I would stroll down Commerce Street, running into everyone we knew and then some, joining up and going back to this one's studio or that one's deck for a drink, then moving on, eating a bit here and there, parties forming on the spotâinvitational parties were rare and never as much funâand maybe ending the evening dancing at the Flagship or the Pilgrim Club, or wherever there was music, which was everywhere.

Oh, it was free and easy. People flirting the night away. Like New York, it never slept. A few men even flirted with me. Well, at least a little. Something that never happened in the city. The only time someone did make a pass at me was during an opening at Martha Jackson's gallery. A young guy had crashed what he thought was a party, gotten drunk, and maneuvered me into a corner. He was quickly ushered out. I always figured I was off limits. After all, a wife was a wife, or at least Clem's wife was Clem's wife. Whatever. But that night confirmed what a small, tight-knit family I had married into. Another lesson learned: There were insiders and outsiders.

And how nice to be an insider in Provincetown. All the same people one saw in the city, but not the same at all. Everyone so laid back and glad-handing. Maybe because it was like a small-town neighborhood where people walked, everything and everybody just a shout away. I think of Milton Avery in front of his house, waving hello and inviting us in. He sat backlit by the sea. Pipe at hand. Sally nearby. Another soul-mated pair, like the Hofmanns. I was always on the alert for what a life partnership might look like. Were there clues I could learn from? If it was possible for others, maybe it would be possible for us.

Milton asked if I would like to have a go at chess. I demurred, saying I barely knew how the pieces movedânot quite trueâall the while kicking myself for the timidity that kept me from sharing a few moments with that kind, gentle man whom I wished I could know better. I, who adored

games of all kinds, had early on backed off chess as being beyond me. After all, it was a man's game and therefore veiled in arcane practices and complexities inaccessible to females. And Milton smiled and said, “Perhaps another time.”

games of all kinds, had early on backed off chess as being beyond me. After all, it was a man's game and therefore veiled in arcane practices and complexities inaccessible to females. And Milton smiled and said, “Perhaps another time.”

Other books

Bodyguard: Target by Chris Bradford

Choc Shock by Susannah McFarlane

A Blossom of Bright Light by Suzanne Chazin

The Magnificent Bastards by Keith Nolan

The Legend of Ivan by Kemppainen, Justin

The Heir and the Spare by Emily Albright

The Void of Muirwood (Covenant of Muirwood Book 3) by Jeff Wheeler

Whistleblower and Never Say Die by Tess Gerritsen

Ray by Barry Hannah

Days of High Adventure by Kay, Elliott