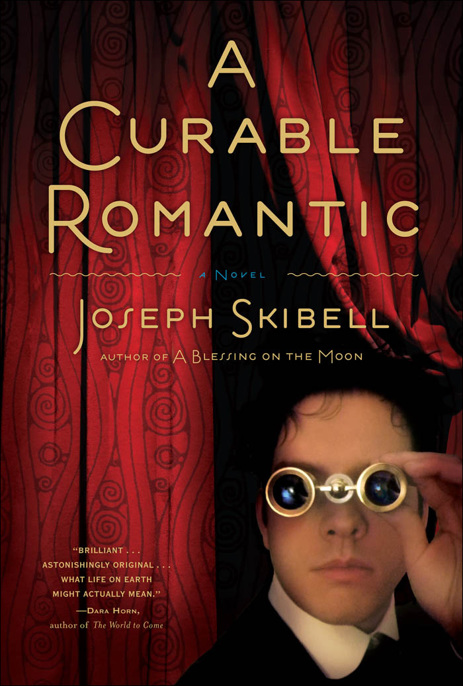

A Curable Romantic

Read A Curable Romantic Online

Authors: Joseph Skibell

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #Jewish, #Literary, #World Literature, #Historical Fiction, #Literary Fiction

A CURABLE ROMANTIC

ALSO BY JOSEPH SKIBELL

A Blessing on the Moon

The English Disease

A CURABLE ROMANTIC

A NOVEL BY

Joseph Skibell

Published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

© 2010 by Joseph Skibell.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published simultaneously in Canada by Thomas Allen & Son Limited.

This is a work of fiction. While, as in all fiction, the literary perceptions and insights are based on experience, all names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

A portion of this novel was published, in slightly different form, in

Maggid: A Journal of Jewish Literature.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Skibell, Joseph.

A curable romantic : a novel / by Joseph Skibell. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN

978-1-56512-929-0

1. Jewish men — Fiction. 2. Vienna (Austria) — Fiction. 3. Freud, Sigmund, 1856 - 1939 — Fiction. 4. Esperanto — History — Fiction. 5. Zamenhof, L. L. (Ludwik Lazar), 1859 – 1917 — Fiction. 6. Warsaw (Poland) — Fiction. I. Title.

PS3569.K44C87 2010

813.54 — dc22 | 2010018605 |

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

For my mother

and for her mother for my daughter

for my daughter and for her mother

and for her mother

And in memory of my father

And the Holy One, what did He do? He buried truth in the ground.

— Genesis Rabbah

A CURABLE ROMANTIC

BOOK ONE

A CURABLE ROMANTIC;

or, My Life in Dr. Freud’s Vienna

CHAPTER 1

I fell in love with Emma Eckstein the moment I saw her from the fourth gallery of the Carl Theater, and this was also the night I met Sigmund Freud. My seat had cost me nearly half a krone. For a full krone, I could have stood in the parterre, but that would have meant going hungry all the following day. I owned no evening clothes. Unbeknownst to my neighbor Otto Meissenblichler, a waiter at the Sacher, I regularly sneaked into his rooms when he wasn’t working or on other occasions when he didn’t need them and took from his wardrobe his black swallowtail coat, his black pants, his black tie, and his white shirt with the gold-and-onyx buttons, restoring the ensemble long before he returned from his own night out, which was usually early in the morning.

Otto possessed a dexterity with women that frankly eluded me, I who had so clumsily dropped and broken every heart so far entrusted to my care.

He was also taller than I, Otto was — perhaps his height accounted for his amorous successes — and his suit was at least two sizes too large. My neck swimming in his collars, his tie drooping to my sternum, his cuffs tucked inside my sleeves, his trouser crotch falling halfway to my knee — was there ever a more ridiculous figure than I?

What woman, other than his own mother, would find such a clown cause for sexual alarm?

None. I knew the answer was none, and so I kept my head down and my long nose in my program, hoping to command no more attention than a shadow if I failed to meet another’s gaze. The men who glanced at me glanced away again quickly, wry grins concealed within their thick beards, and the women accompanying them looked straight through me.

I’d seated myself behind an enormously broad-shouldered man and his enormously broad-shouldered wife. The man’s cape and the woman’s

fox stole, hanging like an arras from their shoulders, formed an impenetrable horizon beneath which I couldn’t see the stage. I watched the audience, therefore, before the curtain, seated on the edge of my chair, peering through the aperture formed by the couple’s shoulders, their heads, and their hat brims.

It was thus, my view framed by the little seahorses of their ears, that I caught my first glimpse of her, my Venus on the half shell, my ill-starred amorette: my Emma Eckstein.

WHAT DREW MY

attention so irresistibly to her? Perhaps it was her broach that caught my eye. A silver angel pinned above her heart, the spangle glimmered and flashed, reflecting back light from the thousand and one gas lamps roaring in the hall. Beneath the pin, her bosom heaved in a pendulous panic as she stepped into the aisle. Verifying the seat number on her ticket stub, juggling her program against the reticule she kept in her other gloved hand, she searched the crowd in front of her (for her seat, I presumed) and behind her (for the companion from whom she’d become unintentionally parted), unable to find either, or both, or perhaps one without the other.

She was nearsighted — I could tell by the way she brought the stub to her face — but too vain to wear her glasses, allowing a squint to mar her forehead, puckering it with a scowl.

I couldn’t help sighing. I’ve always responded, quite often foolishly, to beauty, but it’s the eye, I believe, and not the heart or the groin, that is the organ of desire, the eye that in a convulsive ocular somersault literally turns the world upside down, defying the brain to make sense of it all.

But can the eye be trusted? That is the question. How clearly may it peer into the heart of our attractions, when it’s the nature of beauty to beguile the eye and confound the mind?

And the Fräulein was indeed beautiful. Her nose was straight and fine, and her mouth almost too large for the trembling pedestal of her chin. Her hair, swept off her neck and pinned into place by an opal clasp, frizzled out in small exasperated tufts. She seemed older than I — she must have been nearing thirty — and yet she had about her a frazzled air belonging more properly to a maiden. And indeed, it was this sweet

and mild confusion animating and irritating her every gesture that convinced me the alarums clanging in the belfry of my heart at the sight of her were genuine. I held my breath in anticipation of the arrival of her companion, hoping he would prove to be neither husband nor lover nor (in those strangely liberated times) both. However, the relief I felt upon seeing a mother and not a lover join my darling (already I was thinking of her in this way) disappeared as I watched the Fräulein, obviously chastened by her mother, attempting to decipher the elder woman’s wishes, peering into her face as into a page of incomprehensible scribbling.

I followed their progress down the aisle through my opera glasses but lost sight of them when the head of the man in front of me threw itself up, a big fleshy mountain, between us. Rearing back, I jolted the glasses into the bridge of my nose and was blinded by a yellow flash of pain. Swerving my lorgnette in a panic to the right, lest I lose them, I found the Fräulein and her mother again on the far side of the woman’s plumed hat.

They were speaking to a gentleman, a family friend by the looks of it, although upon closer examination — peering in, I refocused my lorgnette — I could see that the man’s presence seemed to be rattling the younger woman. She seemed smitten by his person. Blushing compulsively, she dropped her head, unable to meet his gaze. Gripping her little purse by its chain, she let it dangle in front of her, as though to conceal the delta of her sex.