A Dash of Style

Authors: Noah Lukeman

THIS IS not a book for grammarians. Nor is it one for historians. They can turn to Lynne Truss's

Eats, Shoots Leaves

or a host of other excellent punctuation books written for them. This book is for the audience that needs it the most and yet for whom, ironically, a punctuation book has yet to be written: creative writers. This means writers of fiction, nonfiction, memoir, poetry, and screenplays, and also includes anyone seeking to write well, whether for business, school, or any other endeavor.

I believe most writers do not want to know the seventeen uses of the comma, or ponder the fourth-century usage of the semicolon. Most writers simply want to improve their writing. They want to know how punctuation can serve

them —not

how they can serve punctuation. They have turned to books on punctuation, but have found most painfully mundane. Unfortunately, many of these books tend to ignore anyone hoping to use punctuation with a bit of style.

This book will offer a fresh look at punctuation: as an art form. Punctuation is often discussed as a convenience, as a way of facilitating what you want to say. Rarely is it pondered as a medium for artistic expression, as a means of impacting the content—not in a pedantic way, but in the most profound way, where it achieves sym-

biosis with the narration, style, viewpoint, and even the plot itself.

Why did Hemingway lean heavily on the period? Why did Faulkner eschew it? Why did Poe and Melville rely on the semicolon? Why did Dickinson embrace the dash, Stein avoid the comma? How could the punctuation differ so radically between these great authors? What did punctuation add that language itself could not?

There is an underlying rhythm to all text. Sentences crash and fall like the waves of the sea, and work unconsciously on the reader. Punctuation is the music of language. As a conductor can influence the experience of a song by manipulating its rhythm, so can punctuation influence the reading experience, bring out the best (or worst) in a text. By controlling the speed of a text, punctuation dictates how it should be read.

A delicate world of punctuation lives just beneath the surface of your work, like a world of microorganisms living in a pond. They are missed by the naked eye, but if you use a microscope you'll find they exist, and that the pond is, in fact, teeming with life. This book will teach you to become sensitive to this habitat. The more you do, the greater the likelihood of your crafting a finer work in every respect. Conversely, the more you turn a blind eye, the greater the likelihood of your creating a cacophonous text, and of your being misread.

This book is interactive. It will ask you to make punctuation your own, to grapple with it by way of numerous exercises in a way you haven't before. You'll discover that working with punctuation will actually spark new ideas for your writing. Writing a new work (or revising an old one) with a fresh approach to punctuation opens a world of possibilities, enables you to write and think in a way you haven't before. Ultimately, you'll find this book is not about making you a better grammarian, but about making you a better writer.

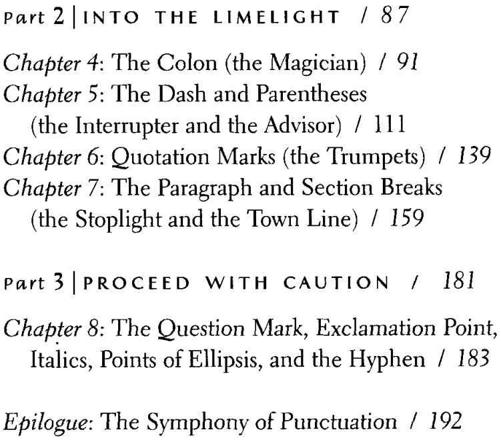

Along these lines, I will not exhaustively catalog every punctuation mark, nor will I examine every usage of every mark discussed. Apostrophes and slashes can be left to grammarians. What interests me are the most important uses of the most important marks, those that can impact a text creatively. I am not concerned here whether an apostrophe goes before or after an "s," or whether a colon precedes a list; I am concerned, rather, whether adding or subtracting a dash will alter the intention of a scene.

The benefits of punctuation for the creative writer are limitless, if you know how to tap them. You can, for example, create a stream-of-consciousness effect using periods; indicate a passing of time using commas; add complexity using parentheses; capture a certain form of dialogue using dashes; build to a revelation using colons; increase your pace using paragraph breaks; keep readers hooked using section breaks. This —its impact on content—is the holy grail of punctuation, too often buried in long discussions of grammar and history.

As a literary agent I've read tens of thousands of manuscripts, and I've come to learn that punctuation, more than anything, belies clarity — or chaos —of thought. Flaws in the writing can be spotted most quickly by the punctuation, while strengths extolled by the same medium. Punctuation reveals the writer. Ultimately, the end result of any work is only as good as the method in getting there, and there is no way there without these strange dots and lines and curves we call punctuation.

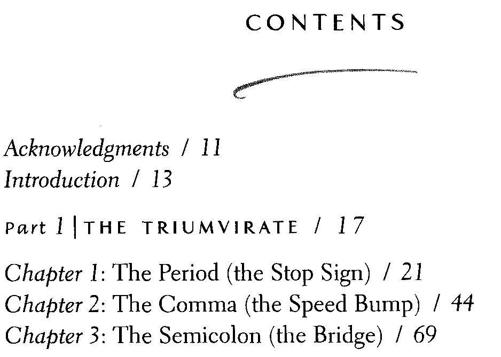

Let's begin by looking at the three crucial punctuation marks—the period, comma, and semicolon —primarily responsible for sentence construction. They can make or break sentences and, as such, have supreme power. Indeed, with these three marks alone you can effectively punctuate a book. It might not be as subtle or complex as a work that contains the additional marks covered in part 2, but it would be perfectly functional. In fact, great authors have punctuated works employing even fewer than these three marks.

As you'll see, these marks sometimes divide, other times connect, yet always they wield power over structure. The period would be impossibly far away if it weren't for the comma and semicolon, which allow a much-needed pause. The comma would be stuck in endless pauses if it weren't for the period to teach it how to stop; and the gracious semicolon wouldn't exist if it weren't for the failure of both the comma and period to fulfill its task.

Consequently, in part 1 we will consider these three marks together: as a triumvirate.

The period is the stop sign of the punctuation world. By providing a boundary, a period delineates a thought. Its presence divides and its absence connects. To employ it is to make a statement; to leave it out, equally so. All other punctuation marks exist only to modify what lies between two periods —they are always restrained by it, and must act in context of it. To realize its power, simply imagine a book without any periods. Or one with a period after every word. Consequently, the period also sets the tone for style and pacing.