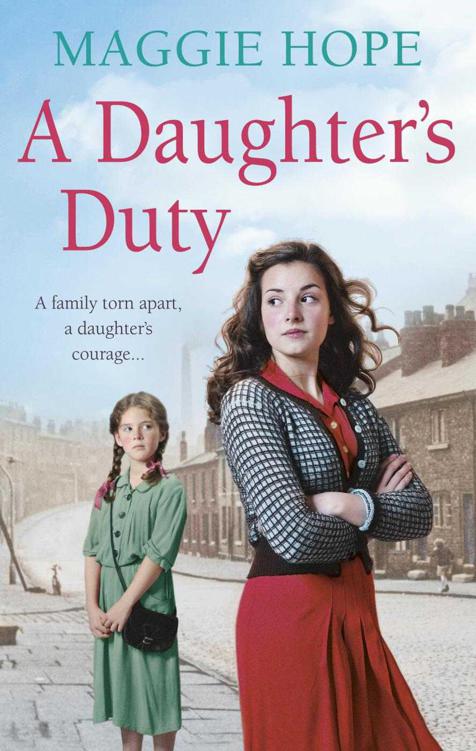

A Daughter's Duty

Authors: Maggie Hope

Contents

She’s bound by her duty to her family . . .

Forced to leave school at the age of fourteen, young Rose Sharpe’s dreams of independence are ruined by her domineering father and constantly ailing mother.

It falls to Rose to bring up her young sister and run the household, with little thanks from either of her parents. Instead she watches as her best friend heads off for her first job, romance and adventure.

But just as Rose has almost given up hope of more than a life of drudgery, she realises she has an admirer of her own . . .

Maggie Hope was born and raised in County Durham. She worked as a nurse for many years, before giving up her career to raise her family.

A Wartime Nurse

A Mother’s Gift

A Nurse’s Duty

A Daughter’s Gift

Molly’s War

The Servant Girl

For Sue and Lol

I am indebted to Keith Armstrong’s

THE BIG MEETING for details of the Miners’ Gala and the quote by David Bean at the beginning of this book.

On the first Durham Miners’ Gala, 1871:

‘One August night, ninety-three years ago, the good people of Durham barred their doors and windows, locked up their spoons and their daughters, called in police reinforcements – and waited for the worst. For the miners – those rough, savage men from the rural pits, who smashed machinery, said rude things to the gentry, beat their wives, ate their children, and squandered their spare time in drink, cock-fighting and gambling – were moving on the city. They were coming, it was whispered round the timid town “to get their reets”.’

David Bean, 1964

‘Howay, Marina. Don’t drag your feet, man. Let’s show them we can –’ But the rest of what Rose was saying was lost to her friend as the band behind them, the Jordan Silver Band, started playing full blast and the colliery banner carried before them billowed in the wind, like a sail on a ship.

‘It’s my new wedgies,’ Marina excused herself. Well, the shoes were a bit higher in the heel than she had been allowed to wear up to now. She glanced down at them, admiring the grown-up look of them. All the fashion they were.

Marina was fifteen years old and this was her first Big Meeting, for there had been none during the long years of the war. Her hazel eyes sparkled and her light brown hair swung out behind her as she threw herself into the dance. The line of girls in dirndl skirts and New Look jackets dipped and swooped in the Palais Glide even though the steps didn’t exactly match the music. They’d come all the way from the station and now they were over Elvet bridge and there was the County Hotel and all the bigwigs on the balcony, grinning at them and waving.

‘Think they’re royalty,’ said Rose, who took an instant dislike to anyone who thought they were something better, but the remark was automatic and she swung round as the line formed a circle and skipped around for a few minutes in front of the balcony, and a crowd of pitlads cheered as the girls’ full skirts caught in the breeze and lifted to a height that wasn’t exactly decent, and Rose squealed and let go of Marina’s hand so as to hold down her skirt, and Marina went careering off to the side and fell into the gutter, bumping into a lad standing there and almost knocking him off his feet too. Her starched petticoat was practically over her head and showing her knickers, which were school regulation bottle green with elasticated legs. Glimpsing them, Marina was mortified. Why wouldn’t Mam let her have cami-knickers like the other girls? And worse, the handbag which had been over her arm fell off and flew open, and lipstick and purse and sandwiches scattered over the pavement.

‘Marina!’ screamed Rose but she was borne away by the others, on their way now to the cricket field where just about all the pitfolk in the county were congregating. Bright red with embarrassment, Marina scrabbled for her belongings and was shoving the burst packet of sandwiches back in the bag when she saw her lipstick almost in the drain and she stretched out a hand for it. The lad she had bumped into was before her and fielded it neatly.

‘Yours, I think?’ he said. She straightened up and pushed her dark hair back, looking into his grinning face. He wasn’t a lad, really, not a pitlad, more likely an undergraduate from the university, she reckoned, as she took the lipstick from him. His hands were too soft and the nails were manicured, for goodness’ sake! In spite of his height and broad shoulders their Lance would call him a nancy boy with hands like that. The thought of her elder brother made her look behind her apprehensively. Lance was carrying the banner with Frank Pearson and if he had seen the lipstick roll out of her bag there would be war on. But the banner was gone, already turning down to the race course where the Big Meeting was held.

‘Thank you,’ said Marina, remembering her manners, and ran off after it, threading her way through the crowds until at last she was on the field. At first she couldn’t see the folk from Jordan and stood looking about her uncertainly. One lad sitting on the grass with his mates, a half-full beer glass in his hand, shouted over to her, ‘You looking for me, pet?’

She blushed and stared across the field to the opposite corner. The pubs were open all day for the gala and, as Mam said, some of the men properly showed themselves up. But thankfully she caught sight of their banner with the picture of Attlee painted on it and ran across to it.

‘You might have waited for me,’ she said, looking reproachfully at Rose.

‘Aw, go on, you couldn’t have got lost, you just had to look for the banner.’ Which was demonstrably true, all the banners were in full sight, with the people of their home villages milling around beneath them. Some of them were draped in black, denoting that lives had been lost in winning the coal but thankfully there had been no big disasters in the past year so on the whole people were happy and out to have a good time.

Rose flopped down on the grass and grinned at her friend, deep blue eyes twinkling with mischief. ‘I knew you’d be all right,’ she said. ‘You are, aren’t you? A good thing you weren’t wearing any nylons, you might have laddered them.’ Her face went solemn at the awful thought. Nylons were as rare as gold dust so soon after the war.

‘I haven’t got any nylons,’ snapped Marina as she too sat down on the grass.

‘There you are then, no harm done.’

‘What do you think, Sam, as many here as before the war?’ Frank Pearson was asking Marina’s father.

‘More, I’d say.’

Marina stared round. It was grand to have everything back to normal. She could hardly remember the last Big Meeting but so far this one was living up to everything she’d heard about the annual event. By, everything was exciting this year. Even though there were still shortages and rationing and everything, folk were happy and today especially as it was Durham Day. The race course was overflowing with people, a lot of them looking about for relatives from other collieries, some already beginning to congregate before the platform where the politicians and labour leaders would be making their speeches. And over to one side there were sideshows and roundabouts and shuggy boats, the first time she had seen them since the war an’ all.

Rose jumped to her feet and caught Marina’s arm. ‘Let’s get away,’ she said.

‘But we’ve just got here,’ Marina protested. Then she saw Rose looking across the field and noticed Alf Sharpe, Rose’s father, standing there. Rose must not want to speak to him. Marina and Rose had been friends for so long they almost always knew what the other was thinking.

‘Righto,’ she said, ‘let’s go.’

Rose caught Marina’s mother’s eye on them and called to her, ‘It’s all right if we go for a walk by the river, isn’t it, Mrs Morland?’ Kate Morland hesitated but Rose had already taken Marina’s arm and was pulling her away.

‘Not for long, mind,’ Kate called after them but her voice was lost in the general hubbub. With an expression that said she didn’t know what lasses were coming to nowadays she turned back to her sister Janie, who lived by the sea at Easington. They hadn’t met since Christmas.

Most of the crowds had already come on to the race course so the two girls made their way back to Elvet bridge fairly easily. A lot of the shops were boarded up but they weren’t interested in shops. They made their way down the steps to the left of the bridge and started to walk along the banks of the Wear. It was a warm day and after a while they climbed up the slope and sank down on the cool grass beneath some trees near the cathedral.

‘By, it’s nice,’ said Rose. She delved into her bag and brought out a couple of apples, tossing one into Marina’s lap. The two girls munched away at the ripe fruit as they watched the sun on the waters of the Wear. Rose flung her head back, running the fingers of one hand through her thick black hair which was much envied by Marina who considered her own to be mousy and far too fine. And Rose’s skin, so white, almost translucent, set her hair off beautifully.

In the distance they could hear the murmur of the crowds on the race course; further along the banks of the river the sound was overlaid by the brassy tones of a speaker coming over the tannoy. But it was all in the distance, the city’s noise muted from here, the traffic banished to the outskirts until the Big Meeting was ended and the bands and their followers marched out in the evening.

‘Is something the matter, Rose?’ asked Marina, who had been covertly watching her friend.

Rose sat up straighter. ‘No, why should there be?’

‘I just thought … you’re all on edge, like. Are you in trouble with your dad?’

‘No, I’m not.’ Rose looked away across the river. She pulled back one arm and threw her apple core so that it skimmed across the water. ‘He’s a bonny lad, isn’t he?’ she said, changing the subject.

Marina looked across at her friend. ‘Who?’

‘You know as well as I do who I mean. Don’t come that,’ said Rose with a scathing glance. ‘That student you bumped into.’

‘He’s all right. I didn’t take very much notice. I’m not interested in boys. I want to get on in life, not be married and a have a kid on the way before I’m eighteen. I’m going to take my School Certificate and my Higher and go to university.’ Marina took another bite of apple and nodded her head to emphasise her words, but Rose wasn’t impressed.

‘Hadaway wi’ you! I saw the way you looked at the lad. You like boys just as much as I do, only I’m more honest. Anyroad, by the time you’ve done all that I’ll have made my money at the clothing factory.’

Rose had started at the Council School the same day as Marina but she had stayed on there after her friend went to the Girls’ Grammar School at Auckland and had left when she was fourteen to work on the band at the factory at West Auckland.