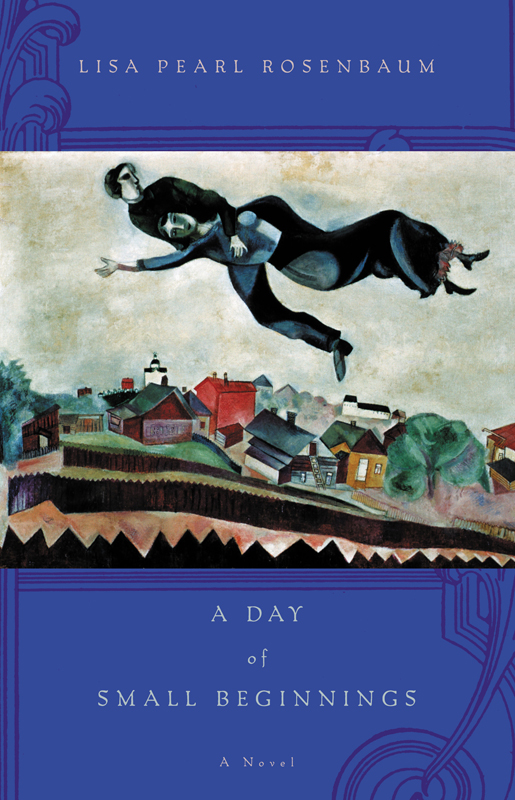

A Day of Small Beginnings

Copyright © 2006 by Lisa Pearl Rosenbaum

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including

information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may

quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: July 2008

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Excerpt from the poem “Separation” by Juliusz Słowacki. English translation copyright © 1995 by Walter Whipple. Used by permission.

Quote from Rabbi Bunam from Pzhysha from

Tales of the Hasidim

. Copyright © 1948, 1972 by Martin Buber. Schocken Books, Random House and Company. Excerpt from the poem by Adam Asnyk from

Poles and Jews: A Failed Brotherhood

by Magdalena Opalski and Israel Bartel. Copyright © 1992 by the Trustees of Brandeis University. Reprinted by permission of

the University Press of New England, Hanover, NH.

A History of the Jewish People

by Max Margolis and Alexander Marx. Copyright 1927 by The Jewish Publication Society of America.

ISBN: 978-0-316-03391-6

Contents

To my family, related or of the heart

They say we stand on the shoulders of the generations that came before us. Years ago, my uncle Lloyd Rodwin told a story about

his trip to Poland in the late 1970s. It wasn’t much of a story, but from its dry bones this novel was born. As head of the

Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT, he had been invited to speak at Warsaw University. Afterward he was offered

a car and driver, a protocol of the Communist era when the government exercised control over the whereabouts of foreign visitors.

He asked the driver to take him to łomże, my grandfather’s birthplace, which he assumed was some backwater town. When they

arrived at a small city with a cathedral, he realized he didn’t know of a single landmark by which he might recognize his

father’s world. Over a lifetime, my grandfather had never described his hometown and my uncle had never asked. At a loss for

what to do, he took a quick tour of the cathedral and the city and returned to Warsaw. The story, scarcely an anecdote, suggested

to me something so uniquely part of the American experience, the loss of one’s family history once the journey to the New

World has been made. I wondered, what if a gatekeeper had remained in the Old World to tell the tale. And so began

A Day of Small Beginnings.

ITZIK

Hear our voices and we will return to you.

1

1

W

HEN

I

WENT TO MY REST IN 1905

I

WAS EIGHTY-THREE AND

childless, aggravated that life was done with me and that I was done with life. I turned my face from the Angel of Death

and recited the Psalm of David:

What do You gain by my blood if I go down to the Pit? Can the dust praise You?

If God’s answer was punishment for my sins or praise for my good deeds, I cannot say.

Understand, I did not call Itzik Leiber to my grave that spring night when my return to the living began. The boy had already

jumped the wall of our cemetery, our House of the Living, as we call it. He was down on all fours, like an animal, looking

for a place to hide. What’s this? I thought.

Sleep, Freidl, sleep, I told myself. An old woman like you is entitled. What did I need with trouble? I was a year in the

grave. My stone was newly laid, still unsettled in the earth. I had no visitors. In death, as in life, people kept their distance.

In our town, a childless woman’s place was on the outside.

And yet, from the hundreds of gravestones that could have hidden him that night, Itzik Leiber chose mine. His knees, his toes

dug into the earth above me. His fingers scraped at the bird with open wings engraved on the dome of my stone. He panted and

he pushed against the indentations of my inscription like an insistent child at an empty breast.

Freidl Alterman, Dutiful Wife,

it read there, as if this explained the marriage.

Itzik Leiber’s small, skinny body smelled of fear’s sweat and the staleness of hunger. But through his fingers his soul called

out to me. Plain as a potato, his soul.

From the outside, he didn’t look like much either. A poor boy, maybe a year past his

Bar Mitzvah.

He had a head the shape of an egg, the wide end on top. And kinky brown hair, twisted up like a nest. His cap was so frayed

the color couldn’t be described. But under the brim, the boy had a pair of eyes that could have made a younger woman blush—big,

sad ovals, and eyelashes like feathers.

I remembered him, of course. In a town like ours no one was a complete stranger. Itzik the Faithless One, they called him.

Faithless? I can tell you Itzik wasn’t faithless that night, not when he whispered against my gravestone, his voice thin as

a thread, “Help me! Please, God, help me!”

God should answer him, I thought. A child’s tears reach the heavens.

Listen to the boy and leave me to my rest,

I prayed. But God had other ideas. Rest would not return to me. Itzik wrapped his arms around my stone, his body curled there

like a helpless newborn. How could I ignore him? I wanted to cradle the petrified child, to make him safe.

In life I liked to say, God will provide. But who could imagine He would wait until after I was gone to the dead to provide

me with a child? Such a joker is God.

A night wind gathered like a flock of birds around our cemetery wall and swept through the thick confusion of graves. The

soft soil began to pound above me with the heavy tread of men. They were so near I could feel their boots making waves in

the earth. What had he done, this Itzik of mine, to incite the Poles to come out so late at night?

Raising myself, I saw torches in their hands, murder on their faces. The faint whiff of alcohol floated over our neighbors

like a demon. You never know what a Pole will do. One minute he’s ready to kill you, the next he’s offering to sell you apples,

smiling, ingratiating, like nothing’s happened. There were as many Poles in our town as there were Jews. But we never counted

them among us, and they never counted us among them.

Itzik whimpered. He gripped my stone with a frenzied, furious fear. His eyes rolled toward heaven.

Make them go away,

he prayed. In the moonlight, his breath formed sharp white puffs that disappeared in the shadows of the gravestones.

I prayed too.

God help him,

I said.

Give the boy’s poor soul a chance to cook, to become a man.

What else could I do for him? I knew I was no

dybbuk

that could invade the world of the living. I had made my journey to

Gehenna

already and eaten salt as punishment for my pride. About this, all I can say is that at least for me it was short, not like

for the worst sinners, who stay in that place eleven months, God forbid. After my time there, I returned to Zokof’s cemetery

to sleep with my earthly body and to wait for Judgment Day.

Itzik pulled at my gravestone so hard it fell over at his feet and broke in two. Who could have imagined that a boy’s clumsiness

would stir me so? My soul tugged and beat at me.

Gevalt,

how it struggled to tear itself from death’s sleep. Such a sensation—frightening and wonderful—the feel of it pushing upward,

freeing itself from the bony cavity once softly bound by my breasts.

I asked God, Is this life or am I again in Gehenna? I never heard of such a state as I was in. But fear was not in me. When

my soul was finally released from my resting place, I hung like a candle-lit wedding canopy over Itzik’s unsuspecting head.

In my white linen shroud, my feet bound with ribbons, I felt lovely as a bride and as proud and exhausted as a mother who

had just given birth.

A tree near Moishe Sagansky’s grave gave a snap. So new was I to being among the living again, I could not be certain who

did this, me or God. The Poles stopped to listen; then one of them looked in my direction and began to holler, “A Jew spirit’s

out!” They took off. Just like that. Such a blessing that the Poles of Zokof were scared of dead Jews. If only they were so

scared of live Jews, maybe we’d have had less trouble with them.