A Disease in the Public Mind (30 page)

Read A Disease in the Public Mind Online

Authors: Thomas Fleming

Few people are aware that the first battle of the Civil War was fought in the streets of Baltimore. The Sixth Massachusetts regiment was attacked as they marched through the city to board a train to Washington, DC. The regiment suffered four dead and seventeen wounded. In return, they killed twelve rioters and wounded dozens. Marylanders blamed the abolitionists of Massachusetts for starting the war.

Library of Congress

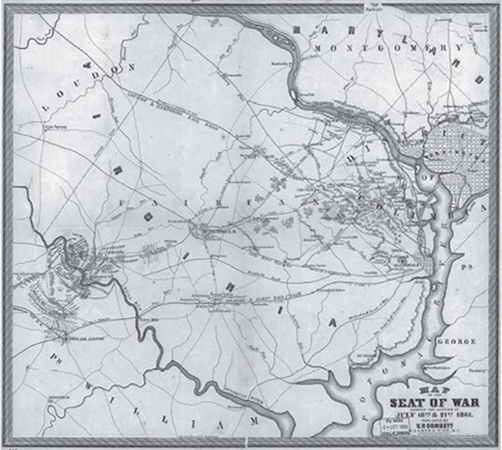

This map, reprinted from

Harper's Weekly

magazine, shows the Union and Confederate armies clashing at Manassas Junction, with Bull Run Creek flowing through the battlefield. General Lee was the unseen planner of the battle. Thanks to his foresight, fresh Southern troops arrived by railroad to overwhelm the weary Union men.

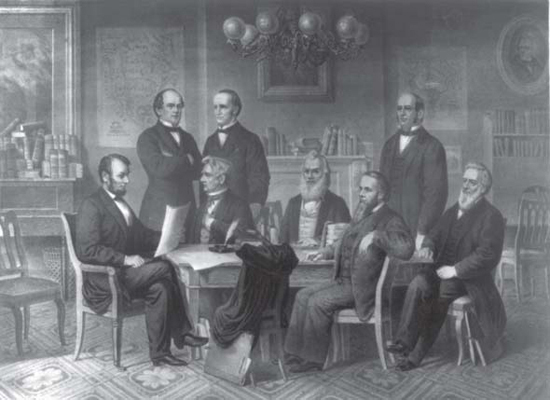

On July 22, 1862, President Lincoln read his first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet. Secretary of State William Seward is on the president's left, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sits midway down the table on the right. Seward persuaded Lincoln not to issue the epochal statement until the Union had won a victory, lest it seem like “the last shriek” of an exhausted government.

Library of Congress

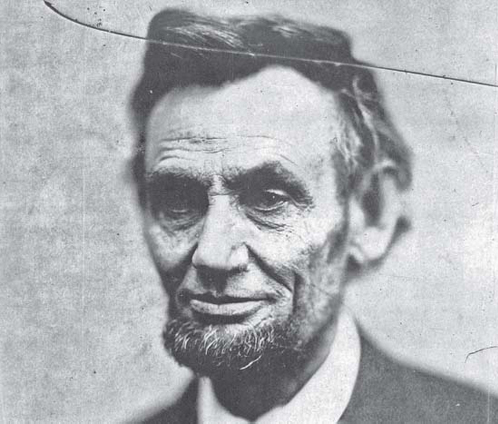

Taken in February 1865, this picture shows the deep weariness that the war inflicted on Abraham Lincoln. But when a senator visited him on April 14, he was amazed by the cheerful, energetic man who shook his hand. The war was virtually over and “The Tycoon,” as his aides called Lincoln, was preparing to forge a peace of reconciliation. Alas, that night he went to the theater.

Library of Congress

The uproar over the Fugitive Slave Act inspired a woman to begin writing a novel that she first published, in the custom of the day, as a serial in a newspaper. Her choice was

The National Era

, Washington, DC's abolitionist paper. Harriet Beecher Stowe was the daughter of the anti-Catholic crusader, the Reverend Lyman Beecher, and the brother of the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, a passionate abolitionist. She called the novel

Uncle Tom's Cabin, or Life Among the Lowly.

The book sold 300,000 copies in the first year of its publication (1852). It also inspired dramatic versions that were soon playing on stages all over America. The instant success of

Uncle Tom's Cabin

is often described as a kind of miracle. But few books have ever been published with more built-in publicity, courtesy of the federal government and the infuriated voices of thousands of abolitionists protesting the Fugitive Slave Law. Central to the book's drama is the flight of slaves to the North and to Canada.

One of the most mesmerizing escapees is the mulatto slave Eliza Harris, who crosses the frozen Ohio River by leaping from ice floe to ice floe with

her five-year-old child in her arms. Eliza was one of two slaves that Arthur Shelby decided to sell to save his Kentucky plantation from debt. The other was Uncle Tom, who rapidly became the most famous African American in real or imagined history. Described as tall and husky, with a wife and family from whom he was cruelly separated, Uncle Tom had a deep Christian faith that inspired him to love and forgive the whites who treated him abominably. He even forgives his last and worst owner, Simon Legree, who whips him to death in a fiendish attempt to break his spirit.

For twentieth-and twenty-first-century readers, Uncle Tom has been too noble to understand or accept. His name has become shorthand for a black man or woman who is ready to knuckle under to white prejudice and abuse. This criticism is an exaggeration, as some contemporary scholars are eager to maintain. They point out that Tom refuses Legree's orders to whip a fellow slave. He also refuses to betray the hiding places of some runaways. But Tom's faith in God's ultimate love, and his anticipation of a reward in heaven if he forgives his persecutors, are not ideas that find much acceptance today.

1

The problem of understanding Tom's extraordinary spiritual life is compounded by the dialect in which he speaks, which seems to underscore his inferiority, if not his simplemindedness. As he parts with his wife, Chloe, who is angry at Arthur Shelby for separating Tom from her and their children, Tom says: “Chloe! Now if ye love me, ye won't talk so, when perhaps jest the last time we'll ever have together. And I tell ye, Chloe, it goes agin me to hear one word agin Mas'r. Wan't he put in my arms a baby?âit's natur I should think a heap of him.”

These words, even at their dialect-distorted worst, are still very important. Harriet Beecher Stowe was adding a dimension to the abolitionist crusadeâpersonal love, or at least pityâfor one of the South's slaves. Unfortunately, Uncle Tom's message was also tragically racist. Mrs. Stowe revealed this sad fact in her own words, in

The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin

, a book she wrote after the novel's success. “The Negro race is confessedly more simple, docile, childlike, and affectionate than other races,” she declared.

Stowe's judgment was based on her religious convictions. “The divine graces of love and faith . . . in-breathed by the Holy Spirit, find in the [Negro's] natural temperament a more congenial atmosphere.” She presented

Eliza Harris and her husband George as far more ready to revolt and challenge slavery in language and action. Stowe attributed their defiance to the white blood in their mulatto veins. With unconscious complacency, Harriet Beecher Stowe created a huge wave of sympathy for slavesâand reinforced white convictions about their own racial superiority.

2

Another interesting aspect of the novel is the almost complete absence of sneering snarling abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison or Wendell Phillips in its text. The only antislavery Northerners the reader sees are kindly Quakers in Ohio, who conceal Eliza Harris and help her escape to Canada. There may be an implied critique in this omission, but it probably was not deliberate. The writing of a novel is a complex psychological process, and the author often wonders as the ideas and images flow onto the page how much control he or she has over the literary imagination while it is at work. At one point, Harriet Beecher Stowe told a close friend that she was not the real author of the book.

“Who was?” the astounded friend asked.

“God,” Mrs. Stowe replied.

3

Another aspect of her view of

Uncle Tom's Cabin

is even more surprising. Mrs. Stowe was disappointed when Southerners reacted to the novel with rage and dismissal. She apparently thought that she had presented many slave owners in a positive lightâand hoped the book would inspire some sort of emancipation movement in the region. In the closing pages of the novel, George Shelby, the son of the original master, travels to Louisiana in an attempt to buy Tom's freedom, but he arrives too late. Tom is dead. Shelby returns to Kentucky and frees all his slaves.

4

The central fact of

Uncle Tom's Cabin

was the way it aroused intense sympathy for slavesâand rage at slave owners. At least as important,

Uncle Tom's Cabin

had huge appeal to the chief readers of novels in the nineteenth century: women. Both reactions are visible in a letter to the author from a woman who had just finished the novel.

I sat up last night long after one o'clock, reading and finishing Uncle Tom's Cabin. I could not leave it any more than I could have left a dying child; nor could I restrain an almost hysterical sobbing for an

hour after I laid my head upon the pillow. I thought I was a thorough-going Abolitionist but your book awakened in me so strong a feeling of indignation and compassion, that I seem never to have had any feeling on this subject until now . . . This storm of feeling has been burning, raging like a fire in my bones all the livelong night.

5

â¢Â      â¢Â      â¢

Uncle Tom was by no means the only new influence on the public mind of the 1850s. A handsome Swiss-born scientist named Louis Agassiz played a large role in the way educated people discussed slavery. Agassiz had come to America in 1846, after winning fame as a scholar of natural history in Europe. Among his more startling discoveries was the existence of the Ice Age. His series of lectures, “The Plan of Creation as Shown in the Animal Kingdom,” created a sensation in Boston. As many as five thousand people showed up to hear him speak, and he had to give each lecture twice to satisfy his enthralled admirers. Soon the newcomer was named head of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard, created specifically for him.

6

In America, Agassiz developed a new scientific passion: anthropology. He leaped into it with the same enthusiasm and self-confidence that had enabled him to churn out an astonishing amount of research on the history of the fish and animal kingdoms. He was galvanized by a Philadelphia scientist, Samuel George Morton, who had spent decades collecting and analyzing human skulls. The key to understanding human abilities, as Morton (and soon Agassiz) saw it, was cranial capacity. He saw humanity not as a unified entity, but as a collection of races. In descending order, these were: Caucasian, Mongolian, Malay, Native American, and Negro. At the top of this not-very-scientific heap were the German, English, and Anglo-Americans, who had the largest cranial capacity. Negroes had the smallest. Not surprisingly, some members of the latter race were, Agassiz concluded, “the lowest grade of humanity.”

Morton's skull collection was totally haphazard. As science it was virtually meaningless. But Agassiz, charging into the new field, swallowed his conclusions in one spectacular gulp, and he used his fame to publicize them

across the nation. Stopping in Philadelphia at a hotel staffed by African Americans, he told of his reaction in these appalling words: “As much as I feel pity for this degraded and degenerate race, as much as their fate fills me with compassion . . . it is impossible to repress the feeling that they are not of the same blood as us. Seeing their . . . fat lips and grimacing teeth, the wool on their heads, their bent knees, their elongated hands . . . I could not turn my eyes from their faces in order to tell them to keep their distance.”

7

Agassiz soon concluded that “the philanthropists”âhis name for abolitionistsâand the defenders of slavery were both wrong. The abolitionists shared his reaction to negritude. They would never let their daughters marry a black man nor would they consider for an instant marrying a black woman. But the slave owners of the South were wrong when they tried to deny that a slave had any right to liberty. Agassiz did not seem to realize that his (pseudo) scientific opinions about the Negroes' intelligence made emancipation seem foolish and even dangerous.

Agassiz was soon telling his Harvard students and eager audiences in Boston that whites and Negroes were two distinct species. He journeyed to Charleston, South Carolina, to tell an assemblage of the city's best people the same thing. “The brain of a Negro is that of the imperfect brain of a seven months infant in the womb of a white,” he said. It was the first of many Agassiz lectures in Charleston. He was as popular there as he was in Boston.

8