A Fortunate Man (7 page)

Authors: John Berger

This individual and closely intimate recognition is required on both a physical and psychological level. On the former it constitutes the art of diagnosis. Good general diagnosticians are rare, not because most doctors lack medical knowledge, but because most are incapable of taking in all the possibly relevant facts â emotional, historical, environmental as well as physical. They are searching for specific conditions instead of the truth about a man which may then suggest various conditions. It may be that computers will soon diagnose better than doctors. But the facts fed to the computers will still have to be the result of intimate, individual recognition of the patient.

On the psychological level recognition means support. As soon as we are ill we fear that our illness is unique. We argue with ourselves and rationalize, but a ghost of the fear remains. And it remains for a very good reason. The illness, as an undefined force, is a potential threat to our very being and we are bound to be highly conscious of the uniqueness of that being. The illness, in other words, shares in our own uniqueness. By fearing its threat, we embrace it and make it specially our own. That is why patients are inordinately relieved when doctors give their complaint a name. The name may mean very little to them; they may understand nothing of what it signifies; but because it has a name, it has an independent existence from them. They can now struggle or complain

against

it. To have a complaint recognized, that is to say defined, limited and depersonalized, is to be made stronger.

The whole process, as it includes doctor and patient, is a dialectical one. The doctor in order to recognize the illness fully â I say fully because the recognition must be such as to indicate the specific treatment â must first recognize the patient as a person: but for the patient â provided that he trusts the doctor and that trust finally depends upon the efficacy of his treatment â the doctor's recognition of his illness is a help because it separates and depersonalizes that illness.

3

So far we have discussed the problem at its simplest, assuming that illness is something which befalls the patient. We have ignored the role of unhappiness in illness, the factors of emotional or mental disturbance. Estimates among G.P.s of how many of their cases actually depend on such factors vary from five to thirty per cent: this is perhaps because there is no quick way of distinguishing between cause and effect and because in nearly

all

cases there is emotional stress present of one kind or another which has to be dealt with.

Most unhappiness is like illness in that it too exacerbates a sense of uniqueness. All frustration magnifies its own dissimilarity and so nourishes itself. Objectively speaking this is illogical since in our society frustration is far more usual than satisfaction, unhappiness far more common than contentment. But it is not a question of objective comparision. It is a question of failing to find any confirmation of oneself in the outside world. The lack of confirmation leads to a sense of futility. And this sense of futility is the essence of loneliness: for, despite the horrors of history, the existence of other men always promises the possibility of purpose. Any example offers hope. But the conviction of being unique destroys all examples.

An unhappy patient comes to a doctor to offer him an illness â in the hope that this part of him at least (the illness) may be recognizable. His proper self he believes to be unknowable. In the light of the world he is nobody: by his own lights the world is nothing. Clearly the task of the doctor â unless he merely accepts the illness on its face value and incidentally guarantees for himself a âdifficult' patient â is to recognize the man. If the man can begin to feel recognized â and such recognition may well include aspects of his character which he has not yet recognized himself â the hopeless nature of his unhappiness will have been changed: he may even have the chance of being happy.

I am fully aware that I am here using the word Recognition to cover whole complicated techniques of psychotherapy, but essentially these techniques are precisely means for furthering the process

of recognition. How does a doctor begin to make an unhappy man feel recognized?

A straightforward frontal greeting will achieve little. The patient's name has become meaningless: it has become a wall to hide what is happening, uniquely, behind it. Nor can his unhappiness be named â as is the case with an illness. What can the word âdepressed' mean to the depressed? It is no more than the echo of the patient's own voice.

The recognition has to be oblique. The unhappy man expects to be treated as though he were a nonentity with certain symptoms attached. The state of being a nonentity then paradoxically and bitterly confirms his uniqueness. It is necessary to break the circle. This can be achieved by the doctor presenting himself to the patient as a comparable man. It demands from the doctor a true imaginative effort and precise self-knowledge. The patient must be given the chance to recognize, despite his aggravated self-consciousness, aspects of himself in the doctor, but in such a way that the doctor seems to be Everyman. This chance is probably seldom the result of a single exchange, and it may come about more as the result of the general atmosphere than of any special words said. As the confidence of the patient increases, the process of recognition becomes more subtle. At a later stage of treatment, it is the doctor's acceptance of what the patient tells him and the accuracy of his appreciation as he suggests how different parts of his life may fit together, it is this which then persuades the patient that he and the doctor and other men are comparable because whatever he says of himself or his fears or his fantasies seems to be at least as familiar to the doctor as to him. He is no longer an exception. He can be recognized. And this is the prerequisite for cure or adaptation.

We can now return to our original question. How is it that Sassall is acknowledged as a good doctor? By his cures? This would seem to be the answer. But I doubt it. You have to be a startlingly bad doctor and make many mistakes before the results tell against you. In the eyes of the layman the results always tend to favour

the doctor. No, he is acknowledged as a good doctor because he meets the deep but unformulated expectation of the sick for a sense of fraternity. He recognizes them. Sometimes he fails â often because he has missed a critical opportunity and the patient's suppressed resentment becomes too hard to break through â but there is about him the constant will of a man trying to recognize.

âThe door opens,' he says, âand sometimes I feel I'm in the valley of death. It's all right when once I'm working. I try to overcome this shyness because for the patient the first contact is extremely important. If he's put off and doesn't feel welcome, it may take a long time to win his confidence back and perhaps never. I try to give him a fully open greeting. All diffidence in my position is a fault. A form of negligence.'

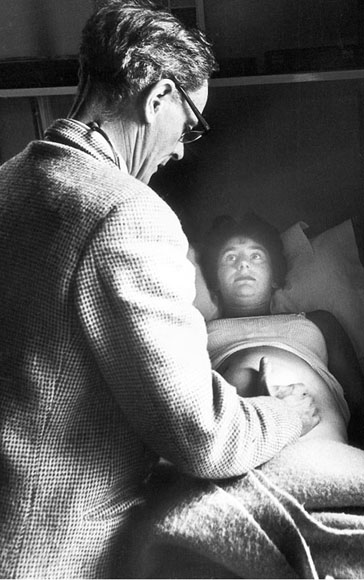

It is as though when he talks or listens to a patient, he is also touching them with his hands so as to be less likely to misunderstand: and it is as though, when he is physically examining a patient, they were also conversing.

Sassall needs to work in this way. He cures others to cure himself. The phrase is usually no more than a cliché: a conclusion. But now in one particular case we can begin to understand the process.

Previously the sense of mastery which Sassall gained was the result of the skill with which he dealt with emergencies. The possible complications would all appear to develop within his own field: they were medical complications. He remained the central character.

Now the patient is the central character. He tries to recognize each patient and, having recognized him, he tries to set an example for him â not a morally improving example, but an example wherein the patient can recognize himself. One could simplify this â for now we are not dealing with the complexities of the average case but with Sassall's motives â by saying that he âbecomes' each patient in order to âimprove' that patient. He âbecomes' the patient by offering him his own example back. He âimproves' him by curing or at least alleviating his suffering. Yet patient succeeds patient

whilst he remains the same person, and so the effect is cumulative. His sense of mastery is fed by the ideal of striving towards the

universal

.

The ideal of the universal man has a long history. It was the working ideal of Greek democracy â even though it depended on slavery. It was revived in the Renaissance and became for a number of men a reality. It was one of the principles of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and after the French Revolution was maintained, at least as a vision, by Goethe, Marx, Hegel. The enemy of the universal man is the division of labour. By the mid nineteenth century the division of labour in capitalist society had not only destroyed the possibility of a man having many roles: it denied him even one role, and condemned him instead to being part of a part of a mechanical process. Little wonder that Conrad believed that âthe true place of God begins at any spot a thousand miles from the nearest land': there, men could fully prove themselves. Yet the ideal of the universal man persists. It could be the promise implicit in automation and its gift of long-term leisure.

Sassall's desire to be universal cannot therefore be dismissed as a purely personal form of megalomania. He has an appetite for experience which keeps pace with his imagination and which has not been suppressed. It is the knowledge of the impossibility of satisfying any such appetite for new experience which kills the imagination of most people over thirty in our society.

Sassall is a fortunate exception and it is this which makes him seem in spirit â though not in appearance â much younger than he is. There are superficial aspects of him which are still like a student. For example, he enjoys dressing up in âuniforms' for different activities and wearing them with all the casualness of the third-year expert: a sweater and stocking cap for working on the land in winter: a deer-stalker and laced leather leggings for shooting with his dog: an umbrella and homburg for funerals. When he has to read notes at a public meeting he

deliberately

looks over his glasses like a schoolmaster. If you met him outside his area, on neutral ground, and if he didn't begin talking, you might for one moment suppose that he was an actor.

He might have been one. In this way too he would have played many roles. The desire to proliferate the self into many selves may initially grow from a tendency to exhibitionism. But for Sassall as the doctor he is now, the motive is entirely transformed. There can be no audience. It is only he who can judge his own âexhibition'. The motive now is knowledge: knowledge almost in the Faustian sense.

The passion for knowledge is described by Browning in his poem about Paracelsus â whose life story was one of the tributaries to the later Faust legend.

I cannot feed on beauty for the sake

Of beauty only, nor can drink in balm

From lovely objects for their loveliness;

My nature cannot lose her first imprint;

I still must board and heap and class all truths

With one ulterior purpose: I must know!

Would God translate me to his throne, believe

That I should only listen to his word

To further my own aim!

Sassall, unlike Paracelsus, is neither a theosophist nor a

Magus

; he believes more in the science than in the art of medicine.

âWhen people talk about doctors being artists, it's nearly always due to the shortcomings of society. In a better society, in a juster one, the doctor would be much more of a pure scientist.'

Or:

âThe essential tragedy of the human situation is not knowing. Not knowing what we are or why we are â for

certain

. But this doesn't lead me to religion. Religion doesn't answer it.'

Yet this difference of emphasis is mostly an historical one. At the time of Paracelsus sickness was thought of as the scourge of God: and yet was welcomed as a warning because it was finite whereas hell was eternal. Suffering was the condition of the earthly life: the only true relief was the life to come. There is a striking contrast in medieval art between the way animals and human beings are depicted. The animals are free to be themselves, sometimes horrific, sometimes beautiful. The human beings are restrained and anxious. The animals celebrate the present. The humans are all waiting â waiting for the judgement which will decide the nature of their immortality. At times it seems that some of the artists envied the animals their mortality: with that mortality went a freedom from the closed system which reduced life here and now to a metaphor. Medicine, such as it was, was also metaphorical. When autopsies were performed and actually revealed to the eye the false teachings of Galenic medicine, the evidence was dismissed as accidental or exceptional. Such was the strength of the system's metaphors â and the impossibility, the irrelevance of any medical science. Medicine was a branch of theology. Little wonder that Paracelsus who came from such a system and then challenged it in the name of independent observation resorted sometimes to mumbo-jumbo! Partly to give himself confidence, partly for protection.