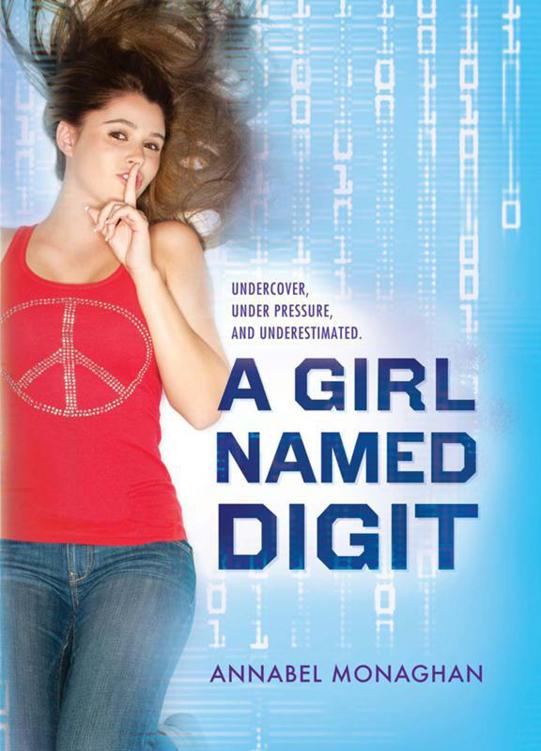

A Girl Named Digit

My Life is Based on a True Story

Honk if You Love Bumper Stickers!!!

Life’s a Beach and Then You Drown

I Keep Pressing “Escape” but I’m Still Here!

Don’t Call Me Infantile, You Stinkybutt Poophead

I Think, Therefore I am Single

When Everything’s Coming Your Way, You’re in the Wrong Lane

99% Of Being Smart is Knowing What You’re Dumb At

I Love My Country. It’s the Government I’m Afraid Of.

If Reality Wants to Get in Touch, it Knows Where I am

So, When’s the Wizard Going to Get Back to You About That Brain?

Don’t Ya Think Hard Work Must Have Killed Someone?

It Doesn’t Take a Genius to Spot a Goat in a Flock of Sheep

Follow Your Dreams, Except the One Where You’re at School in Your Underwear

Romance is Like a Game of Chess: One False Move and You’re Mated

Honk if You Love Peace and Quiet

Alcohol and Calculus Don’t Mix. Never Drink and Derive.

There’s No Emoticon for What I’m Feeling

It’s as Bad as You Think, and They are Out to Get You

The World is Coming to an End. Please Log Off.

May You Live in Interesting Times

I’m One Bad Relationship Away from Owning 30 Cats

The Truly Educated Never Graduate

Actions Speak Louder than Bumper Stickers

Copyright © 2012 by Annabel Monaghan

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Houghton Mifflin is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhbooks.com

The text of this book is set in Apollo MT Std.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Monaghan, Annabel.

A girl named Digit / by Annabel Monaghan.

p. cm.

Summary: After identifying a terrorist plot, a brilliant seventeen-year-old girl from Santa Monica, California, gets involved with the young FBI agent who is trying to ensure her safety.

ISBN 978-0-547-66852-9

[1. Terrorism—Fiction. 2. Kidnapping—Fiction. 3. Interpersonal relations—Fiction. 4. Adventure and adventurers—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.M73649Di 2012

[Fic]—dc23

2011012239

Manufactured in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

4500355303

For Gretel Dennis, inspiration and dear friend.

On the morning of my kidnapping, my mom’s makeup was perfect. After years of training in television and film, she had mastered how to apply exactly the right amount so that she would appear flawless to the camera, while not looking garish in person. Smoky gray eye shadow framed her lids, and the lightest application of mascara—waterproof for the somber occasion—darkened her lashes. She’d lined her lips in what I knew was her go-to lip liner and filled it in with the palest nude lipstick. To the untrained eye, she looked as if she could have woken up like this, at once tragic and gorgeous.

What surprised me more was her outfit, which had taken some serious thought. Our house is painted French blue, with a darkly stained brown door, surrounded by hot pink bougainvillea that creeps down the walls like ivy. She stood perfectly framed in the doorway in a turquoise T-shirt with the thinnest stripe of the same exact hot pink. Her white linen pants looked crisp against the backdrop and picked up the trim around the door. Perfect. I’m sure I’m the only one who noticed this, as everyone else probably focused on the brigade of television cameras that surrounded her. And the fact that she was sobbing.

One guy from CBS yelled out above the others, “Mrs. Higgins, when did you notice she was gone?” She looked down and whispered, “Gone,” and started sobbing again. The hungry reporters realized that, besides the dramatic clip for the evening news promo, they were getting nowhere with her. They turned to my dad, who looked a little disheveled in his normal college professor way, no different at eight a.m. than at eight p.m. Always direct, he spoke right into the camera. “We found the ransom note by the front door at 6:47 this morning. We immediately checked our daughter’s room and found her missing. We called the police at 6:55.”

A chipper young woman from Fox asked, “Does your daughter have a habit of disappearing? Has she ever been in trouble before? Are any of her friends involved?”

My dad squared his shoulders at the camera. “We have a missing seventeen-year-old girl and a ransom note. The police and her mother and I are treating this like what it is—a kidnapping. My daughter has never been in any danger before this.”

NBC local news asked, “Didn’t the ransom note say not to call the police? Aren’t you worried the kidnappers will see this on TV and harm your daughter?” Dad looked like a deer in headlights. Apparently he hadn’t thought this all the way through. The past twenty-four hours had been a blur of constantly changing lies, all strung loosely together. “We have nothing more to say.” He and Mom walked back into the house.

I watched this whole scene from a warehouse in downtown Los Angeles on a six-inch TV with an actual antenna. Big-budget kidnapping. Not. I sat on one of two mismatched upholstered armchairs in a windowless room where I couldn’t even tell night from day. The only reason I knew it was five o’clock just then, besides the replay of my kidnapping story on the five o’clock news, was that my captor came in with dinner.

He caught the tail end of the segment and watched with me as my mom opened the front door for a second time to offer a despondent wave to the cameras. He plopped down in the other chair and smiled. “What do you want to do now?”

Okay, so maybe I’m not really kidnapped. And, okay, maybe this is a little bit fun. And, yeah, maybe my captor, FBI rookie John Bennett, is a little cute in a way-too-old and probably-too-serious kind of way.

I’m not the sort of person who would willingly put herself in the center of the five o’clock news. In fact, I’m not sure that I willingly participated in any of this. The whole thing started with a little math game, and since then I have been along for the ride, running from forces I don’t even totally understand. I’m Farrah Higgins. As much as I wish I were kidding, that really is my name. My mom is an actress and devoted the entirety of the 1970s to worshiping and emulating the Charlie’s Angels in every way possible. I could have been named for Kate Jackson or even Jaclyn Smith. But, no, Farrah Fawcett was the most famous angel, and when I was born my father made the mistake of saying, “She’s a little angel.” And Farrah it was. Trust me, I remember to thank them all the time.

We live in L.A., and I know what people say about us: “L.A. is an intellectual black hole, a cultural void. Their creativity is measured by the number of sequels they’ve produced . . .” And, yes, it bothers me that they think so. My dad’s an intellectual, and my mom is, well, less so. But the environment here is teeming with inspiration and genius. Los Angelenos have been known to create things that the rest of the world finds ridiculous, and others that the world can’t live without. Either way, people are creating something out of nothing, pulling ideas out of the sky. I love it here.

And, no, I don’t even mind the traffic. First of all, the only place I ever drive to is school, so I’m never in such a big hurry to get anywhere. And second, I do some of my best reading in gridlock. I have a secret fascination slash obsession with bumper stickers. I’ve been known to get off the freeway on the wrong exit just for a chance to finish reading the back of someone’s car. I’m baffled that people are just so out there with their thoughts and their identity that they can post their political and religious views on the back of their car for any tailgater to see. And then there’s something about the concise nature of the bumper sticker itself, somehow telling you so much about its owner in ten words or less.

I started collecting bumper stickers when I was ten and had my entire bedroom door covered with them by eleven. I’m picky about the ones I put up and use tape for a few weeks before I actually commit to the peel and stick. My four bedroom walls are now completely covered, each sticker carefully X-Actoed around the window frames and electrical outlets. At the time of my kidnapping, I had covered about one-third of my ceiling, but I’ll never really be finished. I am constantly covering old stickers with new ones, placing more positive messages over ones that spoke to my preteen angst. It was a good day when

ASK ME IF I CARE!

gave way to

WAG MORE, BARK LESS

. For years I’ve gone to bed gazing up at the eternal question:

WHAT IF THE HOKEY POKEY IS WHAT IT’S ALL ABOUT?

I know, I’m a little off topic. But don’t dis L.A.—we’re on the cutting edge of self-expression. Personally, I drive my dad’s old Volvo wagon, and I have nothing on the back. As hard as I try, I haven’t come out of the bedroom with my hobby. I’m still looking for the peel-and-stick representation of my Inner Self. Hey, I’m only seventeen.

It’s my senior year at Santa Monica High School. I have a sixteen-year-old brother named Danny and married parents. My mom’s a not-quite-famous actress—she always has a job, but she doesn’t exactly get mobbed or even recognized at Whole Foods. My dad is head of the math department at UCLA. Yes, that is where all the pocket protectors go to meet other pocket protectors. He’s pretty cool, though, and gives me a lot of space to be un-nerdy and to act like a regular teenage girl. He says my gift can wait, but that I only get one chance to be a kid.

Oh, right, so my gift. If you can call it that. There’s a fine line between a gift and a disability—“special” can mean very different things, depending on who you’re talking about. You could say I’m good at math, but that’s not really it. It’s like my mind never stops calculating things. Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve been able to find patterns in things that other people can’t see. I can take thousands of pieces of data and arrange them in a logical pattern, or I can take seemingly random data and identify the pattern within it. Like when I was eleven months old, I could put together a 300-piece puzzle, 1,000 pieces by the time I was two. By the time I was nine, I was able to see order in a group of 2,000 numbers. My dad would give me temperature statistics, and I would be able to compare them to humidity predictions and tell him whether it was going to rain. This has very little value really, because you can put numbers like this into a computer and it’ll spit out the correlation. The only point is that my mind does this automatically. It was pretty cool until it made me a freak.

In sixth grade I started middle school in a building where the classrooms had the kind of 1960s ceilings that had those big acoustic square tiles with tons of tiny holes in them. If they’d been uniform, I would have been fine. But the rows were uneven, and I was desperate to find order. The first row had 16 holes, then 15, then 16, then 15, then—oh!—17. Anyway, it was obvious that I was wacked, and it was broadcast to everyone in my class when my teacher suggested that I wear a visor to keep me from looking up during class. I tried it and my grades skyrocketed, my social status . . . not so much.

My gift quickly earned me the nickname Digit, which caught on and stuck. By the middle of sixth grade, my elementary school friends were suddenly busy on the weekends, already sitting at a full table at lunch, and generally distant. Where Farrah had been popular in fifth grade for breezing through math assignments with extra time to help out her friends, Digit was a show-off with an obsessive-compulsive disorder. I managed to make a few friends in my accelerated classes, but not the sort of friends who got invited to parties or even had the confidence to show up at school dances.