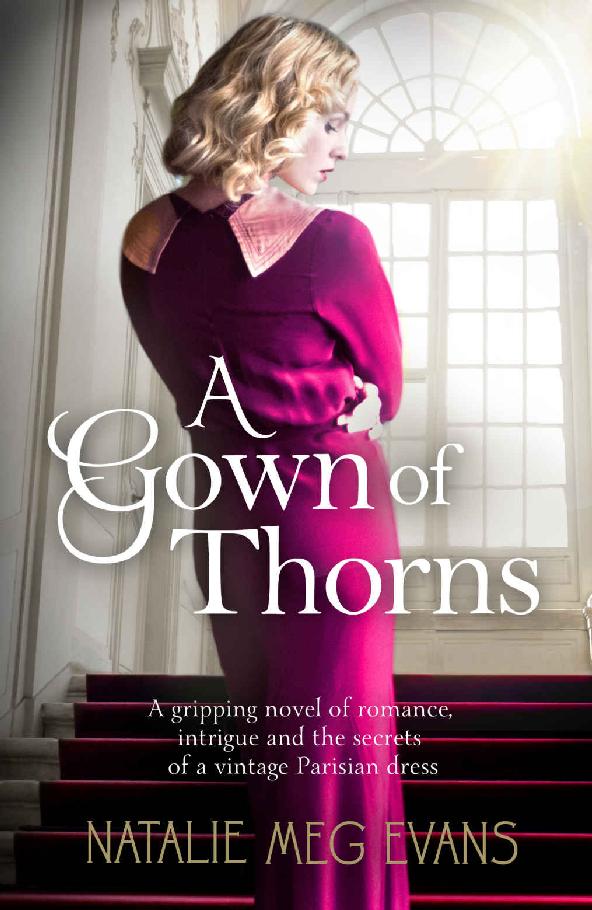

A Gown of Thorns: A Gripping Novel of Romance, Intrigue and the Secrets of a Vintage Parisian Dress

Authors: Natalie Meg Evans

Tags: #Mystery, #Historical Fiction, #French, #Military, #Literature & Fiction, #Romance, #Historical, #20th Century, #British, #Thriller & Suspense, #Genre Fiction

A gripping novel of romance, intrigue and the secrets of a vintage Parisian dress

T

his story is dedicated

to Naomi Bolstridge, my Aunt Omy

T

hese events happened

in the year 2003. Some of us instinctively know that the past is always with us. Those of a scientific disposition resist the idea – until denial becomes, in itself, unscientific.

S

he wheeled

her suitcases towards the ticket office, blinking in the sunshine. After the train’s air-conditioned interior, Garzenac station felt like a bread oven. There ought to be a warning sign:

Redheads, do not alight here

.

The train doors sealed themselves with a gentle

tsssk

and the RER Paris–Bordeaux began to move. Shauna Vincent asked herself,

Why didn’t I research summer temperatures in the Dordogne valley?

If she didn’t get out of this sun, she’d cook.

The ticket office clock said it was just gone three p.m.: the train had come in a few minutes early, so Madame Duval, her soon-to-be employer, might not have yet arrived. Shauna checked her phone for messages, finding only a belated text from her service provider, welcoming her to France. Her phone was down to one bar of signal, she noticed. She couldn’t have charged it properly before she left home. Disturbing. She

never

forgot to charge her phone. Just as she never came out in summer without sun cream in her bag.

She’d bought a map of the Dordogne

département

during a brief stop-off in Paris, and had spent much of the four-hour journey searching for her final destination, a village called Chemignac. It didn’t seem to exist. She’d been expecting a rural backwater, but not complete isolation.

Please

let it not be out of mobile phone range. For her sanity, she needed to keep contact with friends, and with the job market. Two weeks ago, the research post she’d believed was hers had gone to somebody else. The shock of it had soured her final days at university and made the many months she’d taken over her master’s degree feel like a waste of time. It still felt like a bereavement and she’d accepted this last-minute invitation to France as a way of dealing with the rejection. But had she made a catastrophic mistake?

In the station foyer, she looked for a kiosk selling bottled water, but there wasn’t one. Not even a vending machine. Just unmanned ticket barriers. On the station forecourt, she screwed up her nose at the whiff of melting tarmac and scuttled for the shade of some cypress trees. Sudden cool and the scent of balsam calmed her a little. Curious, in spite of herself, to investigate this unfamiliar environment, she pushed aside the feathery foliage. Her eyes fastened instantly on a small, brown insect which was almost indistinguishable from the bark. Evolutionary camouflage in action… Sometimes, the more simple life-forms were, the more intricate their defences. Globs of resin were trickling down the trunk like melted wine gums and she wondered if her little insect might eventually be overrun by it and end up, millennia from now, transfixed as a ‘fly in amber’.

A horn blast reminded Shauna that she had an appointment to keep. Madame Duval might have arrived. She glanced around expectantly, but the car was hooting to get the attention of a delivery driver blocking the station concourse. The delivery man was scanning a parcel, his rear doors gaping, and didn’t even look up as the motorist hooted again. A younger man in a faded green bush hat standing next to him did at least give an apologetic wave.

One by one, drivers who had collected their passengers edged away until only a red, open-top 2CV and a silver Mercedes remained. Shauna trundled her cases towards the Mercedes, the more likely make of car for Madame Duval in her mind. A distant relation on Shauna’s mother’s side of the family, all Shauna knew of Isabelle Duval was that she lived in a wing of the Château de Chemignac, and that long ago she’d been a fashion journalist in Paris. She’d married a diplomat and was now widowed. Shauna was to take care of her grandchildren. She was picturing a woman with impeccably groomed grey hair – Isabelle Duval was in her late sixties – x-ray thin, wearing a little black dress. All right, perhaps not black in this heat… Ivory linen, gold bracelets shimmering at her wrists.

‘Pardon!’ A woman, sweating under the weight of shopping bags, cut in front of Shauna to tap on the Mercedes’ window. As the driver lowered the glass, Shauna realised the car was a taxi. Not her ride, obviously. The only vehicles remaining were the delivery van and the topless 2CV. Hoping she wouldn’t be kept waiting very much longer, Shauna unzipped the smaller of her suitcases and retrieved a cotton shirt. It would protect the back of her neck from the sun. She was fighting to get her arms into it when the young man in the bush hat strode past, the parcel under his arm. He glanced at her through mirrored lenses and she sensed a moment’s interest followed by a dollop of pity.

All right for him, literally taking the heat in his stride. Muscular and brown as tropical teak and with a day’s growth of stubble, he looked local, though the washed-out T-shirt and low-slung Bermudas could have originated anywhere. Buttoning her shirt to her neck, she watched him approach the red 2CV and place his package in the passenger footwell. So carefully, she wondered what fragile object was inside. He then vaulted into the driver’s seat without opening the door. At the turn of his key, music with a heavy bass flared out. Then he was off, hair flying away from his face to reveal dark sideburns and the fact that he was singing.

The delivery van driver finished his paperwork and moved off too, and that’s when Shauna saw there was one last vehicle in the car park. Its driver was holding up a sign reading ‘Chemignac’.

‘Oh my God,’ Shauna breathed. Then, ‘No, please, anything but that.’

I

t was a two-wheeled cart

, a white pony between the shafts. A woman the same age as Shauna – twenty-five or so – was perched on the box seat, reins held loose in one hand. She wore a red singlet and knee-length shorts that showed off endless, tanned limbs. The

de rigueur

sunglasses hid her expression. What looked like honey-brown hair was shoved under a baseball cap. Even the pony wore a sunhat of knitted, tasselled string, fitted around its ears. Every time it tossed its head, the tassels dislodged a cluster of flies.

Fifteen kilometres in the back of a cart?

Shauna wailed silently. She wouldn’t cook, she’d char-grill.

‘What kept you? I’m Rachel, I run the tourist side of things at Clos de Chemignac. Thought you'd missed the train.’

The girl spoke French in a fast, bored style that Shauna struggled to follow. She’d once been pretty handy at the language, but had given it up in Year 10 in favour of sciences. After saying ‘Sorry’ in English, she corrected herself: ‘

Je suis désolée

, I expected Madame Duval—’

‘Get up, will you?’ Rachel interrupted. ‘This is the worst time of day to make a horse stand around. You can see the flies, can’t you?’

Apologising again, though neither the time of day nor the flies could be considered her fault, Shauna heaved her suitcases over the tailgate. She clambered in, finding a place to perch a second or two before Rachel clicked her tongue and sent the pony forward at a trot. They continued at this brisk pace right through the town of Garzenac, giving Shauna little chance to get the measure of the place. It seemed to be comprised of old houses clinging to a hill crowned with a church and the ruined towers of an ancient stronghold. Every residence had closed shutters. Perhaps the town’s folk were hiding inside, against the blistering heat.

Flashes of furnace-pink oleander reminded Shauna that she’d travelled south by a whole ten degrees’ latitude since leaving Sheffield in the north of England yesterday. A headache was climbing the walls of her skull. Again, her fault, as she’d lost her sunglasses. She’d been leaning against the stern rail of the cross-Channel ferry, staring into the gilded wake as the boat navigated out of port. She must have fallen into a waking trance, and her favourite Oakleys had paid the price.

As they bowled along an unshaded road, Shauna pulled her shirt collar as high as it would go. It really wasn’t like her to be scatty or distracted. Problem was, she couldn’t stop brooding about the plum post at Cademus Laboratories, snatched from under her nose by a girl half as qualified as her. A girl who happened to be rich, beautiful and socially well-connected. Shauna didn’t object to a fair fight, but society girls with an inflated sense of entitlement made her angry to her soul. Had things worked differently, she’d have been flat-hunting in the East Midlands, looking for a place to rent close to Cademus’ glass-and-steel HQ. She’d have been shopping for career-minded clothes and reading everything she could about her new employer.

Now, instead of working with a team of internationally renowned scientists, she was going to be au pair to a Frenchwoman’s grandchildren. She was heading to a corner of France as alien as the surface of Mars, with added heat and flies. She could have said no when her mother told her that a distant cousin was desperate for summer help, but she’d shrugged and said, ‘Why not? Nobody else wants me.’ In the same negative mood, she’d said, ‘Fine’ when her mother warned her that the job was for three months. She’d bundled a random selection of dresses, shorts and leggings into one suitcase and filled another with study notes. She’d need some brainwork or she’d go mad – if the heat didn’t get her first. Wanting the reassurance of a familiar voice, she speed-dialled her mother. When her tiny screen flashed its ‘No signal’ message, Shauna called to Rachel over the pony’s clip-clopping hooves, ‘Do you get phone reception at Chemignac?’

‘I wouldn’t know. I don’t bother trying.’

OK, I get the message

, Shauna answered silently.

Or rather, I don’t.

Giving up on her phone, she turned to face the back of the cart to avoid staring into the sun. Vineyards hugged every hill and dip, a this-way-and-that patchwork of emerald rows separated by parched strips of grass. This was wine country, though the occasional pocket of strident yellow announced that somebody was growing sunflowers. She could be travelling into the heart of a painting by Cézanne. To her right, trees followed the course of the Dordogne River. To the left, the ground rose towards hills pock-marked with sand-coloured rock. Heat haze hung over everything and Shauna couldn’t shake that sense of heading into a mirage.

‘You’ll fall in love with Chemignac,’ her mother had promised. But Shauna knew all about false promises. Her mobile buzzed, finally picking up signal, and she found a text message from Grace Fuller, who had been her closest friend at university. Grace, who’d gained a first in physics, was working in a sandwich shop in Sheffield, the city where they’d both grown up.

I’m not the only one whose career has hit a roadblock

, Shauna reminded herself. Grace had written:

Allo, allo? How are ze locals? Anywhere decent to go out? Anyone to go out WITH?

Doubtful on both counts

, Shauna texted back.

Not sure destination exists. Have been picked up by bad-tempered time traveller. Message me every hour for the next three months in case I’ve been abducted.

She pressed ‘send’.

No network

, her phone told her. She tried ‘send’ again. And again, until Rachel turned in her seat and shouted, ‘See up there? There’s Chemignac.’

At the end of an avenue of walnut trees, Shauna made out salmon-red roofs and what looked like a gatehouse with battlements. To one side, wrecking the symmetry, was a squat tower. Then Rachel cried, ‘

Allez, hue!

’ and the pony set off at a furious pace. Shauna’s luggage bounced off the back of the cart. Furious, she roared, ‘Pull up!’

Rachel did so and Shauna scrambled out, jarring her knees on the stone-hard driveway. ‘I’ll walk the rest,’ she said curtly, though she was swaying as if she’d been spun on a fairground ride.

‘Suit yourself. Through the big gate, into the courtyard. Madame Duval lives this side of the château. Look for a rose-pink door. Give the brass bell a good clang, she’s a bit deaf.’

Rachel drove onward while Shauna went to rescue her luggage. The zips had held, thank goodness. Sixty pages of handwritten jottings would have made an interesting addition to the scenery. Hopefully, the homemade elderberry cordial her mother had sent for Madame Duval was still intact. Mouth as dry as tumbleweed, Shauna approached her new home. Château de Chemignac looked to be a hybrid of medieval farmhouse and fortress, with its watchtower and encircling moat. Clay roof tiles shimmered under the four o’clock sun and the sandstone walls had an iron-red sheen. The moat was dry, she discovered – grassed over. She felt the eyeless watchtower questioning her; walking beneath the castellated gatehouse felt like passing through border control. Had she been less exhausted, she’d have fled.

I

n the courtyard

she looked around for a brass bell and instead saw an open-topped 2CV, ladybird-red under a coating of road dust. ‘Haven’t we met already?’ she murmured.

There were two doors facing each other on opposite sides of the courtyard. Both were nail-studded oak, each with a brass bell with a rope attached to the clapper. No rose-pink to be seen. Choosing the nearest, she rang hard, as instructed. Hearing footsteps, she rehearsed her greeting: ‘Madame Duval? I’m Shauna, Elisabeth’s daughter.

Si heureuse de faire votre connaissance

. Please can I have a bucket of water?’

She heard footsteps and a grumbling male cough. Frowning, she glanced again at the red 2CV. Was she about to meet the man with the mirrored sunglasses who liked Guns N’ Roses? She was boiling and sweaty – thanks to Rachel – and in no state to face an attractive man.

The door was wrenched open and Shauna’s smile dropped away as a figure in blue overalls demanded to know what she wanted. True, it was a man, but one whose lined face was dominated by a beaky nose and a bristling white moustache. ‘Who are you?’ he demanded, glowering through ink-black eyes. ‘Why were you trying to pull the rope off the bell,

hein

?’

‘I wasn’t! I mean –’

Je suis desolée

– ‘I’m looking for Madame Duval.’

‘For Isabelle?’ The old man pointed at the door opposite. ‘She isn’t in, though. You’re the English girl? We don’t want you here.’

‘I beg your pardon?’ Shauna took a step back, but the old man seemed unmoved by her dismay.

‘We don’t want you.

Casse-toi,

Anglaise!

’ He slammed the door on her, though not before spitting a final missile –

‘

Rouquine!

’

Rouquine?

Nope. Never heard that one before. Shattered, Shauna dragged her suitcases across the courtyard and rang the other bell. She waited. Squash plants spilled out of half-barrels either side of the door and fat melons grew in an open cold frame. A short hose was attached to an outdoor tap. Beyond caring if the water was suitable for drinking or not, Shauna filled her mouth. The front of her shirt got soaked but it felt wonderful.

After five minutes, she abandoned her luggage and retraced her way through the gatehouse. Beyond the moat stretched acres of uncut meadow, the tall grass turning to hay, jewelled with wild flowers whose scent made her head buzz.

She could search for the employee, Rachel, or even the owner of the 2CV, but frankly, she’d had enough of French people for one day. She’d find a shady spot, she decided, and lie down. She took a shortcut to the meadow, slithering into the dry moat, climbing up the other side. Wading through the grass, her progress marked by bursts of pollen and topaz butterflies, she aimed for the margins of a wood. There the grass was shorter, greener, the air cool. She lay down, her shirt for a pillow. Sleep would cure her.

Sleep came, but brought muddled dreams and the sense of falling into a treacle-black vortex. She dreamt that bullets were zinging past her, fired from the ground, where flames raged.

As she slept and the sun dipped, Chemignac’s doves returned to their roosts under the tower’s conical roof until, without warning, they all shot up into the sky with a sound like whips cracking. Shauna woke.

In the stable yard on the château’s eastern side, a man broke off from cold-sponging the sore, swollen legs of a white pony. He stared up into the violet dusk, expecting to see a circling sparrowhawk or buzzard, but there was nothing to explain the panicking doves. Pulling a face, he remembered coming here as a child to visit his father. In a bid to seem grown-up and brave, he’d insisted on sleeping in the tower room. The doves would often wake him, taking off from their niches as if the tower itself alarmed them. Or something in the tower.