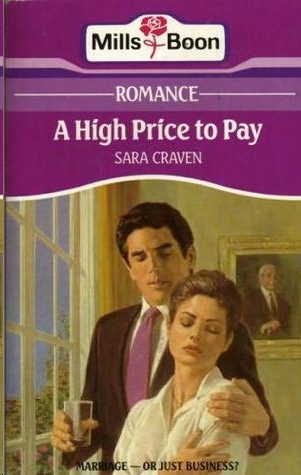

A High Price to Pay

Read A High Price to Pay Online

Authors: Sara Craven

A HIGH PRICE TO

PAY

Sara Craven

What choice did she really have?

Alison Mortimer had felt there was something going on over and

above the appalling reality of her father's sudden death. And Nicolas

Bristow presence confirm your suspicions. Her father, she

discovered, have lost everything in an attempt to save his business.

Even Ladymead, the family home, had gone as security for loans. But

Nicolas Bristow, her father's lender, had not come to evict them. The

terms of settlement Nicolas offer took into account Ally's concern for

sister's future and a mother's peace of mind. At the price of their

happiness, Ally could hardly refuse to marry him!

'THAT man—what's he doing here?'

Alison Mortimer hoped devoutly that her mother's angry whisper to

her had been sufficiently drowned by the organ music to prevent it

reaching the ears of the other mourners in the small church.

And particularly, she thought with embarrassment, the ears of the

man in question, who was stationed only a few pews away.

She'd been conscious of him, of course, from the moment they'd

arrived. Nicholas Bristow was a distinctive figure, not easily

overlooked, and Alison had noticed his tall, black-haired figure with

a twinge of alarm that she'd resolutely told herself was really surprise.

The notice in the paper had said firmly that the funeral service was to

be private, and she hadn't thought Nicholas Bristow a sufficiently

close friend of her late father to ignore such a pointed hint.

She saw gratefully that Uncle Hugh had taken her mother's hand and

given it a comforting pat, while murmuring something soothing, and

registering at the same time the uneasy look he exchanged with Aunt

Beth.

She moved her shoulders restively. There it was again—that feeling,

growing almost to conviction, that there was something going

on—something wrong, over and above the appalling reality of her

father's sudden collapse and death, only a few days before.

If she hadn't been so frantically busy, trying to run the house as usual,

make the arrangements for the funeral, calm her mother, who was

almost hysterical with shock, grief and rage at her loss, and comfort

her younger sister Melanie, summoned home from boarding school

for the funeral, she would have found out what was

happening—pinned Uncle Hugh down, and made him tell her why he

found it so apparently difficult to meet her gaze any more, she

thought grimly.

But once the ordeal of the funeral was behind her, and the obligation

of the buffet lunch waiting for them back at Ladymead had been

fulfilled, she could start finding out.

She could also, she thought, a lump rising in her throat, get a chance

to mourn for her father herself.

She glanced at her mother, ethereal in black, her thin hands nervously

pulling at her handkerchief, and sighed. Catherine Mortimer had

never been a strong woman, physically or emotionally. All her

married life she had depended totally on her husband, and more

latterly on her elder daughter as well. How she would cope with the

everyday realities of widowhood, once the drama of the funeral and,

later, the memorial service, was over, Alison hadn't the faintest idea.

Mrs Mortimer had enjoyed her position as the wife of the area's

leading industrialist. She had loved being asked to take the chair at

local organisations, presiding at dinner parties, and playing the

hostess for housefuls of weekend guestsv although the donkey work

of these occasions had always been left to Alison.

Things would be very different from now on, she thought, although

there would be no shortage of money. Anthony Mortimer had left his

family well provided for from his shareholdings in the light

engineering works which his grandfather had pioneered.

Her mother might have to step down from being the locality's First

Lady, but she would be able to maintain her comfortable existence,

adding to her porcelain collection, and playing bridge with her

cronies. She might even take a greater interest in the day-to-day

running of Ladymead, Alison told herself without a great deal of

conviction.

She knew perfectly well that the mundane details of housekeeping

had never appealed to her mother. She had relied completely on the

elderly and supremely efficient housekeeper, Mrs Wharton, who had

been installed at Ladymead since, her husband's boyhood. And after

Mrs Wharton's death, the chores of making sure everything ran like

clockwork, of engaging staff, and paying the bills had been handed

over, charmingly but definitely, to Alison.

'Such good practice for you, darling, when it comes to running a

home of your own,' Mrs Mortimer had said sweetly.

But Alison hadn't been fooled for a minute. Her mother had been a

dazzlingly pretty woman when she was younger, and Melanie was

blossoming into real beauty with every month that passed, but Alison

herself had been born, and remained, an ugly duckling. She was small

and slight with light brown hair, clear hazel eyes, and a pale skin

which had a distressing tendency to flush when she was disturbed or

embarrassed, and as she was a shy girl, this happened far more often

than she wished.

She had no idea why this should be so. Both her mother and Mel were

miracles of self-possession, and her father had been a cheerfully

ebullient man too.

'You must be a changeling, darling,' her mother had sometimes teased

her.

And sometimes she felt like it, Alison acknowledged ruefully.

Perhaps if her school exam results had been dazzling like Mel's

promised to be, rather than respectable, she might have broken out of

the mould she could see being prepared for her, and insisted on

university and a career of some kind. But with no very firm idea of

what she would like to do with her life, it had been difficult for her to

resist the pressure from her family to stay at home and run Ladymead

for her mother. But she had been determined to achieve at least a

measure of independence for herself, and had managed to find herself

a part-time job in a local estate agent's office. She had been hired in

the first instance under the vague heading of Girl Friday, which

Alison had silently translated as 'dogsbody', but she had amazed

herself, and her new employer, by discovering an unexpected talent

for actually selling houses. In spite of her shyness, she had the knack

of matching properties to potential buyers, many of whom preferred

her quiet efficiency to the 'hard sell' they were often subjected to.

Simon Thwaite, her boss, had concealed his astonishment, given " her

a rise, and asked if she would be prepared to work full time, an offer

she had regretfully had to refuse. He had also asked her out to dinner,

which she had accepted, and they had enjoyed several pleasant

evenings in each other's company.

But that, she knew, was as far as it went. She couldn't see herself

having a serious relationship with Simon, or any of the other men she

came across, and had come to the conclusion that she was probably

one of nature's spinsters.

And probably just as well, she thought without self-pity, because the

evidence suggested that from now on her mother was going to need

her more than ever.

Driving back to Ladymead after the service, Mrs Mortimer was

volubly tearful.

'So much to endure still,' she said, clinging to her brother's arm. 'Dear

Hugh—such a tower of strength! And now this dreadful lunch to get

through somehow.' Her brows snapped together. 'I hope that Bristow

man hasn't had the gall to invite himself to that! If so, you must deal

with it, Hugh. He must be made to see this is a very personal, family

occasion, and that, as a stranger, he is intruding on our grief.'

Hugh Bosworth cleared his throat uncomfortably. 'It might be better

not to say or do anything hasty,' he said heavily. 'After all, Anthony

did a lot of business with the fellow.'

'Did he?' Mrs Mortimer dabbed at her eyes with her handkerchief. 'He

never discussed business matters with me, of course. I've never had a

head for that sort of thing.' A fresh sense of grievance struck her. 'And

I don't understand why Mr Liddell is insisting on going over poor

Anthony's will with me. I know what's in it—he explained it all most

carefully to me, and to Alison when he drew it up. There'll be duties,

of course, but apart from that, he made it all as simple as possible.'

She began to cry again. 'Although I never thought . . . I was always

sure I'd be the first . . .'

Hugh Bosworth patted her shoulder, looking, his niece thought

judiciously, positively hunted. Again she felt that faint

frisson

of

unease. She wished she could have spoken to Aunt Beth, but Mrs

Bosworth was following in the next car with Melanie.

Back at the house, Alison swiftly checked that arrangements for the

lunch had been carried out as impeccably as usual, then went upstairs

to take off the jacket of her simple dark grey suit, and tidy her hair. As

she dragged a comb through her neat shoulder-length bob, she heard

the first of the cars arrive to disgorge its passengers at the front door.

Mentally, she reviewed who should be arriving. As well as Anthony

Mortimer's closest friends, there would be a few of his co-directors

from the works.

She gave a faint sigh. They would be worried. Anthony Mortimer had

been the linchpin of the company, believing in it, backing it to the hilt

always. She wasn't sure how they would replace him.

She gave a last look at herself in the mirror, and grimaced. She could

win a nondescript prize, she thought candidly as she turned away.

And saw from the window Nicholas Bristow alighting from the last

car and standing on the drive, staring at the house.

Alison groaned inwardly. Her mother had overreacted to his presence

at the church, of course, but there was a certain amount of

justification for her attitude. He was a stranger to them, no matter

how close he might or might not have been to her father. He had been

to Ladymead only once before, for dinner, and had annoyed Mrs

Mortimer by spending the latter part of the evening closeted in the

study with her husband.

'So inconsiderate!' Mrs Mortimer had complained fretfully to Alison.

'A dinner party should be a social occasion, and your father knows

how I feel about business being mixed with pleasure.'

Alison had thought wryly that probably her father's wishes has not

had a great deal to do with it. She had had Nicholas Bristow as her

dinner partner, and had found him arrogantly intimidating.

He was the kind of man, she was forced to admit, that most women

would find very attractive. Coupled with that unmistakable aura of

wealth and power which fitted him as well as his elegant clothes, he

possessed an individual brand of compelling, almost insolent good

looks. He probably had charm too, only Alison hadn't been privileged

to encounter it. Eyes as blue and chill as a winter's sky had travelled

over her, remembered with difficulty that she had been introduced to

him on arrival as the daughter of the house, and made it clear he

found her wanting in every respect.

He had responded to her conversational overtures civilly, but without

enthusiasm, and it was obvious that his thoughts were elsewhere most

of the time.

If it hadn't been so hurtful, it would almost have been amusing,

Alison decided, hating him cordially.

She had no time for that kind of sexy male arrogance, and she couldn't

understand what he could possibly have in common with her genial,

outgoing father.