A History of China (69 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

Yet a few Chinese opted for change and reform. Some had been trained in classical Confucianism and passed the civil-service examinations but had begun to question the relevance of the traditional ways and patterns. Paradoxically, Kang Youwei (1858–1927), probably the most renowned of these reformers, actually used Confucianism to legitimize his philosophy. Using his comprehensive knowledge of Confucian texts, he argued that Confucius believed in change to meet changing circumstances. Confucius would not have sided with the conservatives who opposed change and claimed to be the upholders of Confucian beliefs. Kang had not adopted the fervent anti-Manchu attitudes of some reformers, and he apparently believed that the Qing rulers could be persuaded to move in a new direction. Thus, he did not advocate the dynasty’s overthrow and would, in Western terms, be considered a constitutional monarchist. His own ideas smacked of utopianism – a wish for a more egalitarian society – but his advice to Emperor Guangxu (1871–1908) was pragmatic and reflected the moderate reforms championed by the

tiyong

group (which, as mentioned above, advocated protecting the essence of Chinese culture but making use of foreign innovations). His young student Liang Qichao (1873–1929) joined him in his appeal to the emperor. Like some of the other reformers, Liang was also concerned about the roles of women. He believed that women should be offered employment, and also asserted that women should become literate so that they could be better teachers for their children.

By the late Qing, women were becoming more active in demanding rights, although there were considerable setbacks. Demands for the abolition of arranged marriages complemented the campaign against foot binding. The number of girls’ schools increased, and education provided a vehicle for greater activism. Qiu Jin (1875–1907) represented the era’s feminism and activism. Married with two children, she went alone to study in Japan. On her return, she started a feminist magazine that promoted women’s rights. In essays and poetry, she urged women to work so that they could have their own independent incomes. At the same time, she joined secret societies and groups intent on overthrowing the Qing dynasty. The authorities discovered a revolutionary plot with which she was associated and arrested and beheaded her. Despite the efforts of Qiu Jin and other feminists, women did not have the right of divorce and had few, if any, property rights. They also had scant recourse in cases of domestic violence and adultery. Families, husbands, and in-laws could, in theory, sell girls into prostitution or servanthood.

Meanwhile, on the basis of the crisis of the scramble for concessions and the threat of the dismemberment of China, and also on the advice of Kang Youwei and other reformers, the emperor issued a series of edicts from June to September of 1898 to change the Qing. These “Hundred Days of Reform” consisted of practical changes, with scant assertion of ideological or more overarching doctrines. First, the reforms altered the kinds of government officials the Qing would recruit by mandating a new civil-service examination. Instead of emphasizing evaluation of the candidates’ knowledge of the Confucian classics, the examinations would consist, in large part, of questions concerning practical problems that officials might encounter. Similarly, schools and institutes that trained specialists for jobs in the industrial economy would be established, and the curriculum for a university in Beijing would principally be based on Western science, technology, and medicine. The emperor also founded, for the first time in Chinese history, government offices to foster industry and commerce and to produce exports. Instead of using pronouncements and maxims on morality or general policies, the emperor concentrated on very practical matters. He was similarly pragmatic in his approach toward developing a modern army and navy. New weaponry and warships would be manufactured, and at the same time a more sophisticated and disciplined training regimen would be initiated. These reform proposals were down to earth, without any of the grandiose sentiments expressed in Confucian texts.

Yet the emperor and the reformers were naïve. They scarcely sought political and military allies until the very last of the Hundred Days. In September, they contacted military commanders, belatedly hoping to attract the physical force they required to stave off the opposition, which appeared to be mobilizing against the reformers. However, these attempts to recruit military commanders offered the conservatives a pretext for action against the reformers. The empress dowager, with the support of the powerful military commander Yuan Shikai (1859–1916), quickly engineered a coup d’état against her nephew, the emperor, who remained under virtual house arrest for the next ten years. Her agents seized and executed six prominent reformers, though both Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao escaped and fled the country. They would continue to write and their views would continue to evolve, but they would not again play a political role. However, Liang, based mostly in Japan, would propagandize and influence the Chinese students in Japan, who constituted the largest number of overseas Chinese students and a few of whom would play important roles in twentieth-century Chinese history.

The crushing of the reformers who inspired the Hundred Days of Reform had profound implications. Conservatives, flush with victory, began to develop an exaggerated view of their power and of their attempts to reaffirm traditional values. They concluded that, if they acted in concert, they could even tame the foreigners. An antiforeign movement could conceivably overcome the so-called foreign devils. On the other side, some of the reformers concluded that the Qing dynasty would never agree to sharing power or to instituting changes in political life and the economy. Compromise with the dynasty was precluded because of its unreliability and its betrayals during the Hundred Days of Reform. The only alternative was overthrow of the imperial system, for it could not be trusted to embrace change.

OXER

M

OVEMENT

An antiforeign movement, which started outside the court but was subsequently assisted by the Qing, erupted first. Along with bitterness toward foreigners, economic deprivation contributed to the movement and instigated part of the violence. The poor and, to a certain extent, the court elite blamed foreigners for their miserable conditions, which were exacerbated by floods and the resulting chaos, famine, and starvation in Shandong, the province the Germans wanted to claim in the scramble for concessions. Religious conflicts added to the turmoil. Catholic missionaries laid claim to a temple in Shandong that native inhabitants said belonged to them. A local court sided with the Catholics, which embittered the local Chinese population.

Figure 10.2

Too Many Shylocks

, 1901, color litho, Pughe, John S. (1870–1909). Private Collection / © Look and Learn / The Bridgeman Art Library

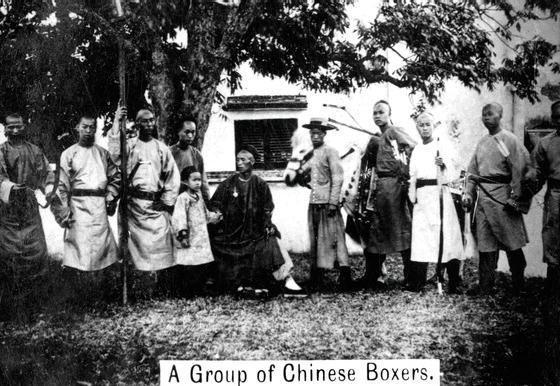

Figure 10.3

A group of Chinese Boxers. Artist: Ogden’s Guinea Gold Cigarettes. London, The Print Collector. © 2013. Photo The Print Collector / Heritage-Images / Scala, Florence

The secret society known as the Boxers (

Yihequan

, or “Righteous and Harmonious Fists”), which opposed Western influence, was the most prominent group in this antiforeign movement. The Boxers, composed principally of poor peasants but including many on the fringes of the rural and urban areas, were disturbed by poverty and the rising force of Christianity, as well as the Western innovation of railroads, which pounded on the earth and generated tremendous noise, disturbing and allegedly damaging the ancestors’ graves as well as ordinary housing. They were also enraged that the railway lines cut across traditional farming plots, that the land adjacent to the tracks was unusable for agriculture, and that people and livestock crossing the tracks were jeopardized and some actually killed. Characterized by specific rituals and symbols, training in the martial arts, and claims of supernatural powers, the Boxers were subverted by a belief that Western weapons could not harm their adherents, who were supposedly immune to bullets and swords. This assertion brings to mind Mao Zedong’s later observation that the atomic bomb was a “paper tiger.” Each reflects a concept of self and its power to deflect seemingly harmful objects. The Boxers were to pay heavily for this misconception. Many contemporary communist historians have praised the Boxers and have portrayed them as anti-imperialists who simply did not have the ideological sophistication and leadership to succeed. They have tended to downplay the Boxers’ violence and fierce antiforeignism. Despite their conservatism, the Boxers recruited women to their cause and employed them to obtain intelligence information, among other responsibilities. The Red Lantern group consisted of young women, the Blue Lantern of middle-aged women, and the Black Lantern of elderly women.

The Boxers reacted violently to the Western presence in China, using their rigorous training in the martial arts. In 1900, their first step entailed opposition to the Catholics’ expropriation of a temple in Shandong. They then damaged or destroyed railroad tracks and telegraph lines and any other items that smacked of the West. They also killed Chinese Christians, and murdered the envoy from the German Empire on June 20, 1900. The province of Shanxi, which was plagued by a drought and the ensuing disturbances, was the site of the so-called Taiyuan Massacre, in which thousands of Chinese Christians were murdered. The most renowned Boxer campaign was the siege of the foreign legations in Beijing from June 20 to August 14 of 1900. The Boxers’ initial successes prompted the Qing and the empress dowager Ci Xi to support them and to appoint officials to command them, but they would not accept court leadership. They surrounded the foreign quarters but did not break through and did not elicit the legations’ surrender. In short, they were disorganized, and no charismatic leader arose to unite the disparate Boxer groups. The inordinate length of the siege permitted the foreign states to organize a relief effort. Britain, Germany, the USA, Russia, France, Japan, Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire raised an army of about fifty thousand to lift the siege. Starting with a victory in Tianjin, the army headed toward Beijing. On August 14, it entered the capital and defeated the Boxers, many of whom fought with rudimentary weapons, believing themselves to be invulnerable to Western bullets, only to learn that they had erred.

The foreign states held both the Boxers and the court responsible for the antiforeign attacks. By blaming the Qing, foreign powers could demand concessions. In September of 1901, they compelled the court to sign a Boxer Protocol, which forced the Qing to execute a number of officials, to suspend the civil-service examinations in a number of provinces, and (perhaps most important) to pay reparations for the losses foreigners had allegedly incurred. China had to make such payments until 1939. The USA used its portion of the reparations to provide scholarships for Chinese students. Discovering that few Chinese candidates knew English, the USA started an English Institute to instruct students in the language. The Institute eventually turned into Tsinghua University, a full-fledged educational organization. Despite this specific benefit, the humiliation of paying reparations was damaging for the Qing’s pride and image. The indemnities were also sizable, exacerbating the chronic financial problems of the Qing court. Many Chinese now turned against the government, while foreigners began to distrust the court. Foreign states, which earlier might have supported the Qing for fear that its collapse would lead to chaos and endanger their economic interests, now were less willing to bolster the court.

OURT

R

EFORMS

Responding to its failures and to renewed pressure, the Qing court rapidly made concessions. In 1902, it forbade the practice of foot binding – certainly a useful means of gaining the attention and support of Westerners in China. In the same year, it permitted the founding of

Nübao

(

Women’s

), the first women’s magazine. Within a the next year, it established ministries of commerce and foreign affairs to foster modern trade and modern international relations. Two years later, it abolished the civil-service examinations, the main source for recruiting officials for at least a thousand years, if not longer. This date (1905) and this decisive step could be said to be the beginning of modern China. The civil-service examinations had been central to the Confucian system. Abolition of this institution, as well as the ensuing impact on government, signified a dramatic change in Chinese civilization. Military commanders, business leaders, and doctors and other professionals could compete for power, and could challenging the traditional relationship between the scholar-officials (who passed the examinations and earned government positions) and the imperial court. The new groups, which were still heavily weighted toward the elite because they were more likely to offer a modern education to their children, sought a clear, written demarcation of powers in government. That is, they would not accept a monarch, with absolute and unrestricted authority, and were eager to share power. Studying both the West and Japan, they demanded a legislature and a constitution. The court reluctantly gave in and sent a mission, resembling the Japanese-dispatched embassy of the early 1870s, to Japan and the West to study their governments. The envoys returned and recommended reforms modeled on the Japanese transformation. In 1908, the Qing thus pledged to set up a constitutional government within nine years, but the court would still dominate the judiciary, the military, and foreign policy, offering little real authority to the new legislators.