A History of the Crusades-Vol 2 (37 page)

Amongst the chief reasons for this failure had

been the difference in habits and outlook between the Franks resident in the

East and their cousins from the West. It was a shock for the Crusaders to

discover in Palestine a society whose members had in the course of a generation

altered their way of life. They spoke a French dialect; they were faithful

adherents of the Latin Church, and their government followed the customs that

we call feudal. But these superficial likenesses only made the divergences more

puzzling to the newcomers.

Had the colonists been more numerous they might

have been able to keep up their occidental ways. But they were a tiny minority

in a land whose climate and mode of life was strange to them. Actual numbers

can only be conjectural; but it seems that at no time were there as many as a

thousand barons and knights permanently resident in the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Their non-combatant relatives, women and old men, cannot have numbered much

more than another thousand. Many children were born, but few survived. That is

to say, apart from the clergy, who numbered a few hundreds, and the knights of

the Military Orders, there can only have been from two to three thousand adult

members of the Frankish upper classes. The combined population of the knightly

classes in the Principality of Antioch and the counties of Tripoli and Edessa

was probably about the same. These classes remained on the whole racially pure.

In Edessa and Antioch there was some intermarriage with the local Greek and

Armenian aristocracy; both Baldwin I and Baldwin II had, when Counts of Edessa,

married Armenian wives of the Orthodox persuasion, and we are told that some of

their nobles followed their example. Joscelin I’s wife and the wife of Waleran

of Birejik were Armenians of the separated Church. But farther south there was

no local Christian aristocracy; the only eastern element was the Armenian blood

in the royal family and the house of Courtenay and, later, the descendants,

royal and Ibelin, of the Byzantine Queen, Maria Comnena.

The Turcopoles

The class of the ‘sergeants’ was more numerous.

The sergeants were in origin the fully armed infantry of Frankish stock, who

settled on the lords’ fiefs. As they had no pride of birth to maintain, they

married with the native Christians; and by 1150 they were beginning to form a

class of

poulains

already merging with the native Christians. By 1180

the number of sergeants was estimated at little more than 5000; but we cannot

tell what proportion remained of pure Frankish blood. The ‘sodeers’ or

mercenary soldiers probably also claimed some Frankish descent. The ‘Turcopoles’,

raised locally and armed and trained after the model of the Byzantine light

cavalry, whose name they took, consisted partly of native Christians and

converts and partly of half-castes. There was perhaps a difference between the half-castes

who spoke their fathers’ tongue and those that spoke their mothers’. The

Turcopoles were probably drawn from the latter.

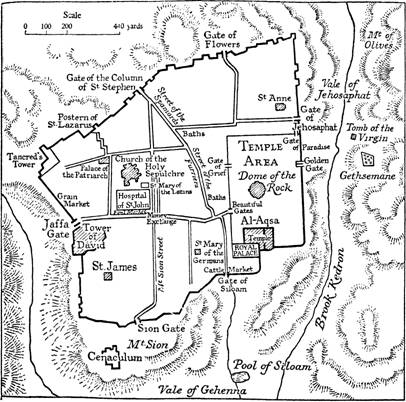

Map 4. Jerusalem

under the Latin Kings.

Except in the larger towns, the settlers were

almost all of French origin; and the language spoken in the kingdom of

Jerusalem and the principality of Antioch was the

langue d’oeil,

familiar to the northern French and the Normans. In the County of Tripoli, with

its Toulousain background, the

langue d’oc

was probably employed at

first. The German pilgrim, John of Wurzburg, who visited Jerusalem in about

1175, was vexed to find that the Germans played no part in Frankish society,

although, as he claimed, Godfrey and Baldwin I had been of German origin. He

was delighted when at last he found a religious establishment staffed

exclusively by Germans.

The towns contained considerable Italian

colonies. The Venetians and the Genoese each possessed streets in Jerusalem

itself. There were Genoese establishments, guaranteed by treaty, in Jaffa,

Acre, Caesarea, Arsuf, Tyre, Beirut, Tripoli, Jebail, Lattakieh, Saint Symeon

and Antioch, and Venetian establishments in the larger of these towns. The

Pisans had colonies in Tyre, Acre, Tripoli, Botrun, Lattakieh and Antioch, the

Amalfitans in Acre and Lattakieh. These were all self-governing communes, whose

citizens spoke Italian and did not mingle socially with their neighbours. Akin to

them were the establishments owned by Marseilles in Acre, Jaffa, Tyre and

Jebail, and by Barcelona in Tyre. Except in Acre, these merchant colonies

numbered none of them more than a few hundred persons.

Native

Christians

,

Moslems

and Jews

The vast majority of the population was

composed of native Christians. In the kingdom of Jerusalem these were of mixed

origin, most Arabic-speaking, and carelessly known as Christian Arabs, almost

all members of the Orthodox Church. In the County of Tripoli some of the

inhabitants were members of the Monothelete sect called the Maronites. Farther

north the indigenous inhabitants were mostly Monophysites of the Jacobite

Church, but there were very large colonies of Armenians, almost all of the

Separated Armenian Church, and, in Antioch, Lattakieh and Cilicia, considerable

groups of Greek-speaking Orthodox. In addition there were in the Holy Land

religious colonies of every Christian denomination. The monasteries were mainly

Orthodox and Greek-speaking; but there were also Orthodox Georgian

establishments, and, especially in Jerusalem itself, colonies of Monophysites,

both Egyptian and Ethiopian Copts and Syrian Jacobites, and a few Latin groups

who had settled there before the Crusades. Many Moslem communities had

emigrated when the Christian kingdom was set up. But there were still Moslem

villages round Nablus; and the population of many districts that were conquered

later by the Franks remained Moslem. In northern Galilee, along the road from

Banyas to Acre, the peasants were almost exclusively Moslem. Farther north, in

the Buqaia, the Nosairi mountains and the Orontes valley there were heretical

Moslem sects acknowledging Frankish rule. Along the southern frontier and in

Oultrejourdain there were nomad Bedouin tribes. Massacres and the fear of

massacre had greatly reduced the number of Jews in Palestine and Christian

Syria. Benjamin of Tudela was distressed to see how small their colonies were

when he visited the country in about 1170. In Damascus alone they were more

numerous than in all the Christian states.

But at some time during

the twelfth century they purchased the monopoly of dye-making from the Crown;

and glass manufacture was largely in their hands. A small Samaritan community

lived on at Nablus.

These various communities formed the basis of

the Frankish states; and their new masters did little to disturb them. Where

natives could prove their title to lands they were allowed to keep them; but in

Palestine and Tripoli, with the exception of estates owned by the native

churches, the landowners had almost all been Moslems who had emigrated as a

result of the Frankish conquest, leaving large territories in which the new

rulers could install their compatriot vassals. It seems that there were no free

villages left, such as had existed in earlier Byzantine times. Each village

community was tied to the land and paid a portion of its produce to the lord.

But there was no uniformity about this proportion. Over the greater part of the

country where the villagers followed a simple mixed agriculture the lord

probably expected enough produce to feed his household and his

poulains

and Turcopoles who lived grouped round the castle; for the native peasant was

not fitted to be a soldier himself. In the rich plains agriculture was run on a

more commercial basis. Orchards, vineyards and above all sugar-cane plantations

were exploited by the lord, and the peasant probably worked for little more

than his keep. Except in the lord’s household there was no slave labour, though

Moslem prisoners might temporarily be used on the King’s or the great lords’

estates. The villagers’ dealings with their lord were conducted through their

headman, called sometimes by the Arabic name of

rais,

sometimes by a

latinized form

regulus

. On his side the lord employed a compatriot as

his factor or

drogmannus

(dragoman), an Arabic-speaking secretary who

could keep the records.

The Fiefs of the

Kingdom

Though there was little change in the lives of

the peasants, the kingdom of Jerusalem was superficially reorganized according

to the pattern of fiefs that we call ‘feudal’. The royal domain consisted of

the three cities of Jerusalem, Acre and Nablus and, later, the frontier town of

Daron, and the territory around them. It had occupied a larger proportion of

the kingdom, but the first kings and especially Queen Melisende were lavish in

the gifts of land that they made to friends and to the Church and the religious

Orders. Further portions might be temporarily alienated as dowers for widowed

queens. The four chief fiefs of the kingdom were the County of Jaffa, usually

reserved for a cadet of the royal house; the principality of Galilee, which

owed its grandiose title to Tancred’s ambition; the Seigneurie of Sidon; and

the Seigneurie of Oultrejourdain. The holders of these fiefs seem to have had

their own high officers in imitation of the King’s. So also did the Lord of

Caesarea, whose fief was almost as important, though it ranked with the twelve

secondary fiefs. After Baldwin II’s reign tenure was based on hereditary right,

females succeeding in default of the direct male line. A tenant could only be

evicted by a decision of the High Court after some gross misdemeanour. But he

owed the King, or his superior lord, a fixed number of soldiers whenever it was

required of him; and it seems that there was no time-limit to their service.

The Count of Jaffa, the Lord of Sidon and the Prince of Galilee owed a hundred fully

armed knights, and the Lord of Oultrejourdain sixty.

The size of the fiefs was variable. The secular

fiefs had been set up by conquest and formed solid blocks of land. But the

estates of the Church and the Military Orders, which had grown chiefly through

charitable gifts and bequests or, in the case of the Orders, from strategical

convenience, were scattered throughout the Frankish territories. The unit in

which estates were measured was the village, or

casal,

or, very rarely,

a half or a third of a village; but villages also varied in size. Round Safed,

in northern Galilee, they seem to have averaged only forty male inhabitants,

but we hear of larger villages round Nazareth and smaller villages round Tyre,

where, however, the general population was thicker.

Many of the lay-lords also owned money-fiefs.

That is to say, they were granted a fixed money revenue from certain towns and

villages and in return had to provide soldiers in proportionate numbers. These

grants were heritable and almost impossible for the King to annul. As with the

landed fiefs he could only hope that the possessor would die without heirs, or

at least with only a daughter, for whom he had the right to choose a husband or

to insist on the choice of a husband out of the three candidates that he

proposed.

The Constitution

The royal cities were obliged to produce

soldiers, according to their wealth. Jerusalem was scheduled for sixty-one,

Nablus for seventy-five and Acre for eighty. But they were provided not by the

bourgeoisie but by the nobility resident in the city, or owners of

house-property there. The leading ecclesiastics also owed soldiers in respect

of their landed estates or house-property. The bourgeoisie paid its

contribution to the government in money taxes. Regular taxes were levied on

ports and exports, on sales and purchases, on anchorage, on pilgrims, on the

use of weights and measures. There was also the terraticum, a tax on bourgeois

property, of which little is known. In addition there might be a special levy

to pay for some campaign. In 1166 non-combatants had to pay ten per cent on the

value of their movables; and in 1183 there was a capital levy of one per cent

on property and debts from the whole population, combined with two per cent on

income from the ecclesiastical foundations and the baronage. Beside the produce

that their villages had to provide, every peasant owed a personal

capitation-tax to his lord; and Moslem subjects were liable to a tithe or

dime

which went to the Church. The Latin hierarchs continually tried to extend the

dime

to apply to Christians belonging to the heretic churches. They did not succeed,

though they forced King Amalric to refuse an offer made by the Armenian prince

Thoros II to send colonists to the depopulated districts of Palestine by their

insistence that they should pay the

dime.

But even with the

dime

the Moslems found the general level of taxation lower under the Franks than

under neighbouring Moslem lords. Nor were Moslems excluded from minor

governmental posts. They, as well as Christians, could be employed as

customs-officers and tax-collectors.