A History of Zionism (107 page)

Read A History of Zionism Online

Authors: Walter Laqueur

Tags: #History, #Israel, #Jewish Studies, #Social History, #20th Century, #Sociology & Anthropology: Professional, #c 1700 to c 1800, #Middle East, #Nationalism, #Sociology, #Jewish, #Palestine, #History of specific racial & ethnic groups, #Political Science, #Social Science, #c 1800 to c 1900, #Zionism, #Political Ideologies, #Social & cultural history

There were celebrations that day in New York, in Palestine, and wherever Jews lived. Traffic stopped in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem as people danced in the streets until the early hours of the morning. The decision imposed heavy responsibility on the yishuv and the entire Jewish people, Ben Gurion said in an interview. ‘After a darkness of two thousand years the dawn of redemption has broken’, declared Isaac Herzog, the chief rabbi. ‘It looks like trouble’, said Dr Magnes, who for many years had fought valiantly and vainly for a bi-national state.

*

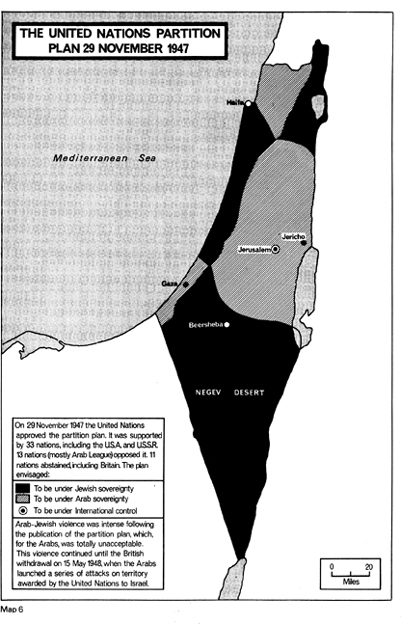

The next morning the Palestinian Arabs called a three-day protest strike, and Jews in all parts of the country were attacked. On that first day of rioting seven were killed and more injured; the fighting continued to the end of the mandate. The next months, as chaos engulfed Palestine, were a time of crisis for the Jewish community. Britain announced that it would leave the country by 16 May 1948, but the administration made no preparations to transfer power to Jews and Arabs, nor indeed to the Committee of Five which had been appointed by the

UN

to administer Jerusalem. The most pressing task facing the Jewish population was to strengthen its defences, since the Arab countries had already announced that their armies would enter the country as soon as the British left. Syria was not willing to wait that long: an ‘Arab Liberation Army’ inside Palestine was established in February with the help of Syrian officers as well as irregulars.

Hagana was by no means as well equipped and trained a fighting detachment as was commonly believed. Its forces and equipment were sufficient to cope with a civil war, but they seemed inadequate to defend the yishuv against regular armies. While Britain continued to supply arms to the neighbouring Arab countries, and America had declared a general arms embargo, the Jewish forces had great difficulty in obtaining supplies. By February the Arab forces were on the offensive throughout the country. While they did not succeed in capturing Jewish settlements, they all but paralysed the traffic among them, and even Jerusalem was about to become a besieged city. The Jewish relief force sent to the help of the Ezion settlements had been wiped out to the last man, a terrible loss by the standards of those days.

At the

UN

the Palestine Commission reported despairingly that nothing could be done before the end of the mandate. They could not demarcate the frontiers or set up a provisional government in the Arab state, and this would prevent economic union, and jeopardise the Jewish state and the international régime for Jerusalem.

*

The British announced that they could not support the

UN

resolution because it committed the Security Council to carrying out the partition scheme or giving guidance to the Palestine Commission. Palestine sterling holdings in London were blocked and the country expelled from the sterling bloc. It seemed as if London was determined to wreck whatever chances remained for an orderly and peaceful handover. Perhaps it wanted to demonstrate that the Palestinian problem was intractable and that where Britain had failed, no one else could succeed.

As events in Palestine took a turn for the worse, as far as Jewish interests were concerned, the resolve of the United States to support partition, never very strong, was further weakened. Senator Austin, telling the Security Council on 24 February that his country was not really bound by the recommendation of the General Assembly, prepared the way for the retreat. On 18 March he formally declared that since the partition plan could not be put into effect peacefully, the attempt to implement it should be discontinued and a temporary trusteeship established by the

UN

. Only a day before this announcement Truman had assured Weizmann that the United States was in favour of partition and would stick to this policy.

The shift in the American position was not apparently the result of a carefully thought-out political line; it simply reflected the drift, the lack of resolution and coordination in the American capital and the conflicting views within the administration. The trusteeship proposals were unrealistic, for if the

UN

had no authority to send a police force to supervise partition, who was going to enforce trusteeship? But events in Palestine had their own momentum, and the country was moving towards partition. In April Truman informed Weizmann that there would be no change in the long-term policy of the United States. If partition was not reversed in the General Assembly, and if after 15 May a Jewish state came into being, Washington would recognise it.

During March and April the military situation in Palestine suddenly improved for the Jews. It was still doubtful whether Hagana would be able to withstand the attack of Arab regular armies, but the main Arab guerrilla forces near Jerusalem and Haifa were routed. Fighting became more intense and savage, as acts of reprisal followed one another. On 8 April, most of the inhabitants of the Arab village of Dir Yassin on the outskirts of Jerusalem, 254 in number, were killed by a combined

IZL

-Sternist force. Three days later, a Jewish medical convoy on its way to the Hadassa hospital on Mount Scopus was ambushed in the streets of Jerusalem with the loss of seventy-nine doctors, nurses and students. A British force stationed two hundred yards away did not intervene.

As the armed struggle became more bitter, the Jews were fighting with their backs to the wall, whereas the Arabs could take refuge in neighbouring countries. By the end of April, about 15,000 Arabs had left Palestine. What impelled them to do so has been debated ever since. The Arabs claim that the Jews, by massacres and threats of massacre, forced them out and that this was part of a systematic policy. The Jews asserted that the Palestinian Arabs followed the call of their leaders, believing they would soon return in the wake of victorious Arab armies.

As the end of the mandate drew nearer, the Jewish organisations prepared for the establishment of the state. Manpower was mobilised, emergency loans floated; the name of the new state, its constitution, flag, emblem, the seat of government were discussed, and there were hundreds of other questions to be decided. In reply to Washington’s trusteeship proposal, the Jewish Agency executive resolved on 23 March 1948 that immediately after the end of the mandate a Jewish government would take over. The Jewish Agency (at its meeting of 30 March) and the Zionist Council (on 6-12 April) decided on the establishment of a provisional government to be called

Minhelet Ha’am

(National Administration) and a provisional parliament,

Moezet Ha’am

(National Council).

*

On 20 April, these terms were first used in the Palestinian press. The new government was to consist of thirteen members and the council of thirty-seven; they were to be located for the time being in the Tel Aviv area. Thus the era of the Zionist institutions in the history of Palestine came to an end.

The mandate was due to end at midnight, 14 May, but the new Jewish administration began to function several weeks earlier. The blue and white flag was hoisted on public buildings in Tel Aviv, new stamps were issued, the taxation services reorganised. (One of the main problems facing the new administration was to find a sufficient number of Hebrew typewriters.)

†

Meanwhile in New York and Washington the Americans and the

UN

went through the motions of establishing a caretaker commission as zero hour approached. But a report from the Consular Truce commission in Jerusalem announced that partition in the capital was already a fact. Officials in Washington thought that the chances that the Jewish state, if proclaimed, would survive, were not very good. Moshe Shertok was warned by General Marshall, the secretary of state, that if the Jewish state was attacked it should not count on American military help. There were suggestions by Dean Rusk and others that the proclamation of the state should be postponed for ten days, perhaps longer, and that meanwhile the truce should be restored.

Shertok arrived in Tel Aviv on 12 May, just in time for the session of the provisional government which was to decide on the proclamation of the state. He supported the proposal that a truce should be declared and that, while a government should be appointed at the end of the British mandate, the proclamation of the state should be delayed. But Ben Gurion was not willing to budge. The motion was defeated by a vote of six to four, as, with a small minority, was the suggestion that the proclamation of the state should mention its borders as defined by the United Nations.

*

The state of Israel came into being at a meeting of the National Council at 4 p.m. on Friday, 14 May 1948 (

Iyar 5

, 5708), at the Tel Aviv Museum, Rothschild Boulevard. The

Hatiqva

was sung first, and then David Ben Gurion read out the declaration of independence: ‘By virtue of the natural and historical right of the Jewish people and of the resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations we hereby proclaim the establishment of the Jewish state in Palestine to be called Israel.’ This took little more than fifteen minutes, after which the members of the council signed the document in alphabetical order. Rabbi Fishman pronounced

Shehekheyanu

, the traditional benediction (… that we lived to see this day …). The first decree adopted by the National Council as the supreme legislative authority was the retroactive annulment of the White Paper. The ceremony was over well before the Sabbath set in. Ben Gurion said to one of his aides: ‘I feel no gaiety in me, only deep anxiety as on 29 November, when I was like a mourner at the feast.’ Half an hour before midnight the last British high commissioner left Haifa, and the following Sunday Dr Weizmann was elected president of the new state.

The first country to recognise the new state was the United States. President Truman made a brief statement to that effect on Friday, shortly after 6 p.m. Washington time. Within the next few days the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, Uruguay and other countries followed. A cable was received by the chairman of the Security Council from the Egyptian foreign minister: the Egyptian army was crossing the borders of Palestine with the object of putting an end to the massacres raging there, and upholding the law and the principles recognised among the United Nations; military operations were directed not against the Palestinian Jew but only against the terrorist Zionist gangs. During Friday night, the invasion of Palestine began. On Saturday morning Tel Aviv’s power station and Aqir airport were attacked from the air. It was the beginning of a series of wars which was not to end for many years.

*

Jewish Frontier

, August 1945.

*

R.R.R. Srossman,

A Nation Reborn

, London, 1960, p. 70.

*

Eban, ‘Tragedy and Triumph’, p. 280.

†

Central Zionist Archives. File S 5/351. Meeting of 7 October 1945.

*

The World Zionist Conference

, London, 1945, p. 6.

†

Speech in Atlantic City,

JTA Bulletin

, 23 November 1945.

*

Yehuda Bauer,

Flight and Rescue: Brichah

, New York, 1970, p. 320.

†

Ibid.

, pp. 317–18.

*

Supplementary Memorandum by the Government of Palestine including Notes on Evidence Given to UNSCOP up to July 12, 1947

, p. 34.

†

Ch. Weizmann,

The Right to Survive

, Jerusalem, 1946.

*

Cmd. 6808, London, 1946, p. 11.

†

David Horowitz,

State in the Making

, New York, 1953, p. 94; Silverberg,

If I Forget Thee, O Jerusalem

, p. 307.

‡

Central Zionist Archives, Meeting of 21 May 1946, File S 25/1804.

*

Quoted in Bauer,

Flight and Rescue

, p. 256.