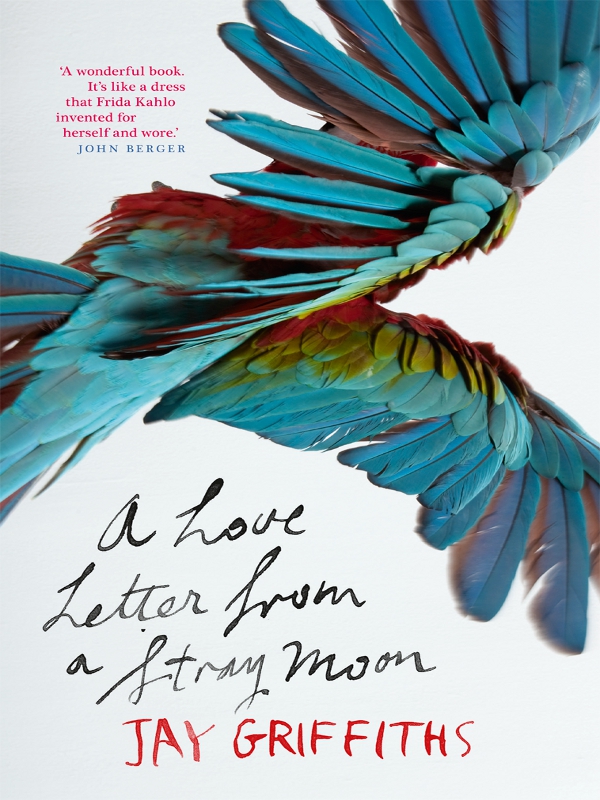

A Love Letter from a Stray Moon

âJay Griffiths'

A Love Letter from a Stray Moon

is a stunning allegory about love, art, and revolution. She makes every word, every scene, in this passionate narrative count. It's brilliant work.'

BARRY LOPEZ

âFrida Kahlo's life and work were indivisible, and with a power worthy of her subject Jay Griffiths has found a way of writing Kahlo's broken, prolific life. Through Griffiths we hear the voice of Frida Kahlo herself, as if she were speaking directly to us. It's like reading poetry inside a great biographical novel. I absolutely devoured this wonderfully perceptive and sensitive book. I already knew a lot about Kahlo's life but rediscovered her in these pages from the inside out.'

MARIE DARRIEUSSECQ

âAn extraordinarily beautiful and sustained prose poem, a call for engagement with the world, and a powerful and astonishing feat of literary and retroactive telepathy. It is a book about possession, in many forms, each of which is sparked by a particular urgency: to comprehend, to celebrate, and to endure.'

NIALL GRIFFITHS

âA rich and extraordinary vision. It's unrestrained; it's as if Jay Griffiths had decided to put everything she knew and felt into this passionate poem of admiration and love for the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. There's something entirely tropical about the uncompromising richness and intensity of the story, and yet it is a story: there is a strong narrative pulse. There are few people who can write stories like this, though. Jay Griffiths is a fearless adventurer with words and images. I salute her courage and the splendour of this vision.'

PHILIP PULLMAN

Photo: EDWARD PARKER

Jay Griffiths is a British writer, author of

Pip Pip:

A Sideways Look at Time

and

Wild: An Elemental Journey

. She is the winner of the Barnes & Noble Discover Award for the best new non-fiction writer to be published in the USA and the inaugural Orion Book Award, and has been shortlisted for the Orwell Prize and a World Book Day award.

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Jay Griffiths 2011

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in 2011 by The Text Publishing Company

Cover and page design by Susan Miller

Typeset in Mrs Eaves by J & M Typesetting

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Author:Griffiths, Jay.

Title: A love letter from a stray moon / Jay Griffiths.

Edition: 1st ed.

ISBN: 9781921758027 (pbk.)

Subjects: Kahlo, Frida--Fiction. Rivera, Diego,

1886-1957--Fiction.

Dewey Number: 823.92

Contents

The Moon's Instructions for Loss

To Diego and All Who Have Wings

If You are Too Easily, Dangerously, Enchantable

My Changeling Child in a World Mad with Grief

I

have always wanted wings. To fly where I belong, to become who I am, to speak my truths winged and moon-swayed.

When I was a small girl, I rehearsed my flight. I dreamt of flying. I jumped off walls and flew, but only down. I wanted to fly up; I needed wings. My hope was winged but it wasn't enough. I jumped when I walked and I photographed myself just by blinking, catching the bright flight of the moment, airborne, between each blink. My friends said that I was graceful, that I made little leaps as I walked, so I floated like a bird, but they also teased me terribly, my friends, and cut me out of their games because polio had damaged my leg, and they called me peg-leg. I learned to swear and practised on them as much as I could, telling them they were

hijos de puta

and I was going to the fucking moon.

One evening, the moon rising, I was out playing in the courtyard and my father called me in, his eyes intense, brimming with the pleasure he knew he was about to give me. My mother hugged me and set me on the floor in front of her.

âMy little angel,' she said, and gave me a wrapped box to open. Never patient, I ripped off the packaging and there inside was a white dress with wings like an angel. I gasped with delightâthey knew,

they knew

! It was as if they had looked into my heart and seen what I longed for. I tore off my clothes, flung them into the corner and put on the dress, the wings white and perfect at my shoulders. In the soaring moment, with all the transfixed delight which a child can feel, my spirit as fluent as the Rio Grande and my arms unfurled like an eagle's wings, I ran to the courtyard, knowing that I would fly, so I jumped for the moon. And fell to earth, horribly.

I was shattered and broken-hearted, and I sobbed while my parents laughed kindly, âOh, Frida, Frida, of course they are not real wingsâ how could they be real?' How could they

not

be real? I thought, because flight is real and hope is real and magic is real, and I cried furiously. These were more real to me than anything, and I had no wish for substitutes. They ask for flight, kids do, they ask for flight and only get straw wings. I could not fly and it felt as if there were ribbons from my skirts which were nailed into the ground. I could not fly but I had to.

My first memory was of the idea of the moon. Our schoolteacher was weird, with a wig and strange clothes, and she was standing in a darkened classroom while we were hushed with surprise as her face was lit from underneath by a candle she was holding. It jagged her features and jangled her face to a skull, like children on the Mexican Day of the Dead turning themselves into spookies by shining torches up under their chins. In her other hand, she held an orange and she told us that the sun (the candle) lit the earth (the orange) and the moon, but she didn't have three hands and the moon was pure idea, an exile present only in its name. (Present in my mind, though, full and shining.) This was the widening universe, so overwhelming that I pissed myself. The teachers made me take off my wet dress and put on some clothes from another girl and I hated that kid from then on. That night I stared unblinking at the moon until my eyes were watering and I knew I would fly there one day.

Before I flew to the moon, though, I dragged that girl across the road and started strangling her and to this day I remember her tongue writhing out of her mouth. The baker came by and yanked me away from her but I didn't care because I knew I would fly to the moon and she wouldn't.

I recovered from polio, and I grew fierce, boxing, playing football and swimming, and I remember those days of skates, bicycles and boats as if it was a girl's boyhood, those days when I was as sleek and disobedient as an otter, tempestuously playful and revelling in it. I was sent to catechism class with my sister and we escaped and went to an orchard to eat quinces. I will never forget how sweet was the fruit of our disobedience in that orchard.

I scampered quicksilver through my childhood, out to being a naughty teenager when everything tasted of wine, melons and chilli. I wore a peaked cap and men's suits so they tutted, the neighbours,

who does she think

she is?

I scorned themâI scorned all those who scorned meâand I took a cigarette lighter and darted towards the hems of their shawls till they squawked and flapped my hands away. (And the

trompetilla

sniggered to the cactus.) In my gang at college we played havoc, in all the keys of chaos. Cleverer, quicker, droller and better read than most of the teachers, we exploded with anarchy and mischief. We got hold of a donkey, one day, and rode it through the college, falling about laughing at the stale-faces who tried to tell us off. We caught a stray dog and tied it up with fireworks, and lit them so the dog shot off dementedly around the corridors. Poor dog, I thought later. At the time, I was drunk, giggling like a skellington in wellingtons, flowers sprouting from my skull. What flower?

Ix-canan

, in its Mayan name, the guardian of the forest, which they also call the firecracker bush.

I was fifteen and I carried a world in my satchel: books, quotes, notebooks, butterflies, drawings and flowers. I cut my hair like a boy, wore overalls, and my eyes shone with devilry and love. The stale-faces called me irreverent. Absolutely not, I snapped, I revere Walt Whitman, Gide, Cocteau and Eliot, Marx, Hegel and Engels, Pushkin, Gogol and Tolstoy. We were terrible show-offs: âAlejandro, lend me your Spengler, I don't have anything to read on the bus!' I cried to my clandestine lover. We went busking, playing the violin in the Loreto Garden, listening to the organ-grinders and skating at dawn. In imagination, we climbed the Himalayas, rowed down the Amazon and sauntered across Russia. I read the imaginary biography of the painter Paolo Uccello and adored it so much that I learned it off by heart.