A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy (2 page)

Read A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy Online

Authors: Thomas Buergenthal,Elie Wiesel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #United States, #Biography, #Social Science, #Personal Memoirs, #Europe, #History, #Historical, #Military, #World War II, #World War; 1939-1945, #Holocaust, #Jewish Studies, #Eastern, #Poland, #Holocaust survivors, #Jewish children in the Holocaust, #Buergenthal; Thomas - Childhood and youth, #Auschwitz (Concentration camp), #Holocaust survivors - United States, #Jewish children in the Holocaust - Poland, #World War; 1939-1945 - Prisoners and prisons; German, #Prisoners and prisons; German

Had I written this book in the mid-1950s, when I made a first attempt to tell part of my story by publishing an account of

the Auschwitz death march in a college literary magazine, this memoir would have conveyed a greater sense of immediacy. Unencumbered

by the mellowing impact that the passage of time has on memory, particularly painful memories, I could then still clearly

recall my fear of dying, the hunger I experienced, the sense of loss and insecurity that gripped me on being separated from

my parents, and my reactions to the horrors I witnessed. The passage of time and the life I have lived since the Holocaust

have dulled those feelings and emotions. As the author of this book, I regret that for I am sure that the reader would have

been interested in that part of the story as well. But I am convinced that if these feelings and emotions had stayed with

me all these years, I might have found it difficult to overcome my Holocaust past without serious psychological scars. It

may have been my salvation that these memories faded away over time.

My Holocaust experience has had a very substantial impact on the human being I have become, on my life as an international

law professor, human rights lawyer, and international judge. It might seem obvious that my past would draw me to human rights

and to international law, whether or not I knew it at the time. In any event, it equipped me to be a better human rights lawyer,

if only because I understood, not only intellectually but also emotionally, what it is like to be a victim of human rights

violations. I could, after all, feel it in my bones.

From Lubochna to Poland

IT WAS JANUARY

1945. Our open railroad cars offered little protection against the cold, the wind, and the snow so typical of the harsh winters

of eastern Europe. We were crossing Czechoslovakia on our way from Auschwitz in Poland to the Sachsenhausen concentration

camp in Germany. As our train approached a bridge spanning the railroad tracks, I saw people waving at us from above, and

then, suddenly, loaves of bread came raining down on us. The bread kept coming as we passed under one or two more bridges.

Except for snow, I had eaten nothing since we had boarded the train at the end of a three-day forced march out of Auschwitz,

only a few days ahead of the advancing Soviet troops. The bread probably saved my life and that of many others who were with

me on what came to be known as the Auschwitz Death Transport.

At the time, it did not occur to me to connect the bread from the bridges with Czechoslovakia, the country of my birth. That

came years after the war, usually on those occasions when, for one reason or another, I was asked to present a birth certificate.

Since I did not have one, I would be required to provide an affidavit, attesting — “on information and belief” — that I was

born in Lubochna, Czechoslovakia, on May 11, 1934. Whenever I signed one of these documents, I would invariably have a flashback

to those bridges in Czechoslovakia.

Not long after the Communist regime collapsed in Czechoslovakia in December of 1989, I finally managed to obtain my birth

certificate. It confirmed what I had claimed in my many affidavits and provided the impetus for a visit by my wife, Peggy,

and me to Lubochna — she out of curiosity to see where I was born, and I in order to connect with that one piece of land on

earth where I first opened my eyes.

We reached Lubochna, a small resort town in the lower Tatra Mountains in today’s Slovakia, after driving for a few hours on

winding roads, alongside noisy brooks and meandering rivers, from Bratislava, its capital. Without having planned it, we arrived

in Lubochna in May 1991, almost fifty-seven years to the day of my birth there. A beautifully sunny day greeted us as we drove

into this small town surrounded by the inviting, mellow mountains, which distinguish the lower Tatras from the harsher high

Tatras.

Now I understood why my father had dreamed of one day coming back to Lubochna and why my mother had loved it here. It seemed

such an idyllic place. As Peggy and I walked through the town in the hope of finding what used to be my parents’ hotel, I

realized that but for the official-looking piece of paper that forever linked me to Lubochna, nothing else did. We never found

the hotel — I later learned that it had been demolished sometime in the 1960s. Although my visit confirmed to me that Lubochna

was truly the beautiful place my parents frequently talked about, I realized with considerable sadness that for my family

and me this town represented little more than a historical footnote in a story that began here with the joy brought on by

the birth of a child, a story that gradually gave way to what became a very different tale.

My father, Mundek Buergenthal, had moved to Lubochna from Germany shortly before Hitler came to power in 1933. Together with

friend Erich Godal, an anti-Nazi political cartoonist working for a major Berlin daily, he decided to open a small hotel in

Lubochna, where Godal owned some property. The political situation in Germany was becoming ever more perilous for Jews and

for those who opposed Hitler and the ideology of his Nazi party. My father and Godal apparently believed that Germany’s enthusiasm

for Hitler would wane in a few years and that they would then be able to return to Berlin. In the meantime, the proximity

of Czechoslovakia to Germany would allow them to follow developments there more closely and enable them to provide temporary

refuge to any of their friends who might need to leave Germany in a hurry.

My father was born in 1901 in Galicia, a region of Poland that belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire before the First World

War. German and Polish were the languages in which he received his primary and much of his secondary school education. His

parents lived in a village on a farm that belonged to a wealthy Polish landowner whose extensive agricultural estate was administered

by my paternal grandfather, an unusual occupation for a Jew at that time in that part of the world. The Polish landowner had

been my grandfather’s commanding officer in the Austrian army and took him into his service when they both returned to private

life. Eventually, he put my grandfather in charge of his many farms.

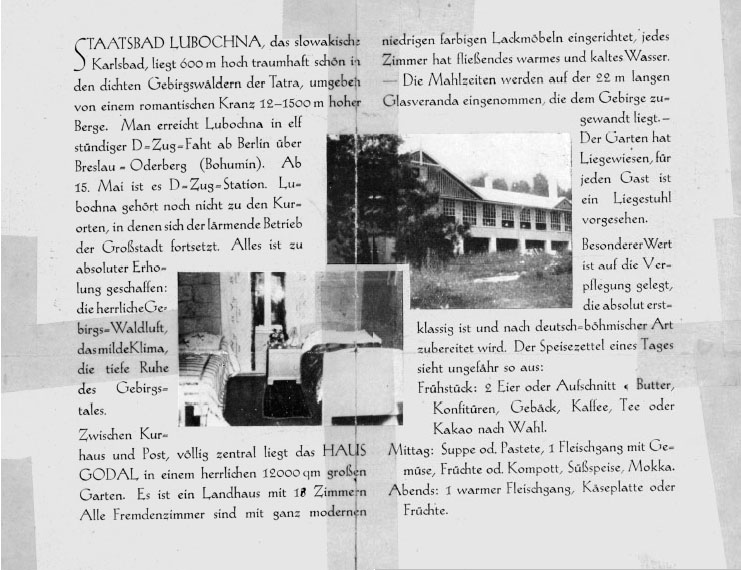

Pages from the hotel prospectus of Haus Godal, the Buergenthal family hotel in Lubochna

Pages from the hotel prospectus of Haus Godal, the Buergenthal family hotel in Lubochna

The nearest high school my father could attend was located in a town some distance away. Family lore has it that, to get to

that school, my father boarded for a time at the home of the flagman in charge of a strategically located railroad crossing.

Trains going to and from that town would pass the crossing a few times a day. Since there was no train station nearby, the

flagman would slow down the train in the morning and then again in the afternoon to enable my father to jump on and off. Later,

less hazardous arrangements were made for him to attend school.

After graduating from high school and a brief stint in the Polish army during the Russo-Polish War that began in 1919, my

father enrolled in the law school of the University of Krakow. Before completing his studies, however, he left Poland and

moved to Berlin. There he joined his older sister, who was married to a well-known Berlin couturier, and obtained a job with

a private Jewish bank. He rose rapidly through the ranks, becoming an officer of the bank at a relatively young age due to

his success in helping to manage the bank’s investment portfolio. His position at the bank and his brother-in-law’s social

contacts enabled him to meet many writers, journalists, and actors living in Berlin. The rise of Hitler and the ever-increasing

attacks by his followers on Jews and anti-Nazi intellectuals, quite a number of whom were friends of my father, prompted him

to leave Germany and settle in Lubochna.

Gerda Silbergleit, my mother, or Mutti to me, arrived at my father’s hotel in 1933. She came from Göttingen, the German university

town where she was born and where her parents owned a shoe store. Not quite twenty-one years old at the time — she was born

in 1912 — her parents had sent her to Lubochna in the hope that a vacation in Czechoslovakia would help her get over the non-Jewish

boyfriend who wanted to marry her. They also thought that it would be good for their daughter to leave Göttingen for a while.

There, the harassment of Jews — and, in particular, of young Jewish women — by Nazi youths roaming the streets was making

life increasingly more unpleasant for her.

When making arrangements for my mother’s stay at the hotel, her parents asked that she be met at the German-Czech border.

Instead of sending his driver, my father decided to drive alone to the border, where he gave her the impression that he was

the hotel’s chauffeur. She was quite embarrassed when at dinner she was seated at the table of the hotel’s owner, who turned

out to be the driver she had quizzed about Mr. Buergenthal, whom her mother had described as a very eligible bachelor. Years

later, whenever I heard my mother tell this story, I wondered whether her visit to Lubochna had been arranged by her parents,

in part at least with a possible marriage to my father in mind, and whether, if there were such a plan, my father was in on

it. Was it just a coincidence that his hotel was recommended to my grandparents by a friend who also knew my father well?

I never did get the whole story, assuming there was more to it. To my mother, it was always love at first sight, and that

was it!

Gerda and Mundek Buergenthal, circa 1933

My parents were engaged three days after they met at the German-Czech border. They were married a few weeks later, but not

until my maternal grandfather, Paul Silbergleit, and then my grandmother, Rosa Silbergleit née Blum, had traveled to Lubochna

to pass judgment on the bridegroom. They were apparently somewhat taken aback by the rapidity of the engagement and the prospect

of a hasty marriage, but it was 1933, and there was little time for courting. I was born some eleven months later. By 1939

we were refugees on the run, only a few steps ahead of the Germans. A whole country, it seemed, had declared war on a family

of three whose only crime was that they were Jews.