Read A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy Online

Authors: Thomas Buergenthal,Elie Wiesel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #United States, #Biography, #Social Science, #Personal Memoirs, #Europe, #History, #Historical, #Military, #World War II, #World War; 1939-1945, #Holocaust, #Jewish Studies, #Eastern, #Poland, #Holocaust survivors, #Jewish children in the Holocaust, #Buergenthal; Thomas - Childhood and youth, #Auschwitz (Concentration camp), #Holocaust survivors - United States, #Jewish children in the Holocaust - Poland, #World War; 1939-1945 - Prisoners and prisons; German, #Prisoners and prisons; German

A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy (20 page)

I spent a great deal of my free time in Göttingen on sports. I joined a table tennis club and a sports club, and played soccer

to exhaustion with Fritz Schügl and other boys from school and from the neighborhood. I swam in the city’s outdoor pool and

in an abandoned stone quarry that was supposed to be off-limits. Fritz and I explored the countryside on our bikes and spent

hours cleaning and oiling them. When I developed an interest in girls, we would join our classmates in the evenings, parading

up and down the main street while ogling the girls and trying to arrange dates with them. There were parties and dancing and

some drinking. In short, I lived the very normal life of a German teenager.

There were only a handful of Jews in Göttingen when I arrived there. Most of them were quite old. The unelected leader of

this minuscule Jewish community was Richard Gräfenberg, the scion of one of the oldest, if not the oldest, Göttingen Jewish

family, whose ancestors had received a “

Freibrief

” (license), allowing them to settle in the town as early as the late Middle Ages. Mr. Gräfenberg, who by the time I met him

was very old, had been able to live peacefully in Göttingen throughout the war, apparently because his wife was not Jewish

and also because she had good connections to the town’s Gestapo chief. Gräfenberg had been able to keep his family home, which

consisted of a large house and a beautiful garden with many fruit trees. From time to time, I was allowed to pick some of

the apples, pears, and plums growing in his garden, a special privilege in those days of scarcity of almost everything edible.

Mutti, who acted as Mr. Gräfenberg’s deputy community leader — that sounds almost funny now, considering that there were probably

no more than six or seven Jews in town, including us — had to visit him every month in connection with the distribution of

the food packages the community received from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. They had to be picked up from

Hildesheim, the town’s district seat, or from the former concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen, which functioned as a displaced

persons’ camp at the time. It was Mutti’s job to make these trips, and I would occasionally accompany her. The packages contained

not only food but also American cigarettes and coffee, both highly valued black-market currency items in those early postwar

days. These could be traded for just about anything, from butter and meat to Persian rugs and jewelry. The people distributing

the packages in Hildesheim and Bergen-Belsen not only tried to cheat us but would also suggest that Mutti was a fool not to

claim that there were more Jews living in Göttingen in order to keep the surplus for herself. That would make her terribly

angry, and on the way back she would always complain that the wrong people had survived the camps. It annoyed her even more

when I reminded her that we too had survived. Of course, she was thinking of my father and would assert that, if he had lived,

he would long ago have cleared those thieves out of the distribution centers. After Mr. Gräfenberg died, Mutti succeeded him

as president.

As soon as I arrived in Göttingen, Dr. Reitter became my surrogate father. He was a gentle, kind, and most patient human being

whom I came to love and admire. He helped me with my homework, taught me how to study, and encouraged me to read and to discuss

what I had read. I was also very much attracted to his extensive medical library, particularly the anatomy and dermatology

books with pictures of naked women, which I studied surreptitiously when neither he nor Mutti were around. Although Dr. Reitter

had been a pediatrician in Poland, he decided to specialize in dermatology in Göttingen because, as he put it, “Pediatrics

is too strenuous a medical specialty for someone with my heart problems,” and he would add, “I no longer have the strength

to make house calls.” I had noticed that he would swallow some heart medication from time to time, particularly when we had

to walk uphill from town toward the Wagnerstrasse where we lived. Once in a while he would take me to visit the university’s

dermatology clinic, show me the wards where patients with venereal diseases were housed, and explain how some of these diseases

were contracted and what happened to people in the final stages of these ailments. I loved those excursions with him and decided

that I would one day study medicine. In the meantime, I used to practice writing my signature in the German way with the doctor

title — Dr. med. Thomas Buergenthal — I expected to earn.

Our excursions to these clinics became gradually less and less frequent. I noticed that whenever we had to walk up even the

smallest incline, Dr. Reitter would have to stop often and take his heart pills. He complained of chest pain and found it

increasingly harder to breathe after even the slightest exertion. As that pain got more intense, his cardiologist decided

to have him admitted to the hospital; I believe he may have had a minor heart attack. Mutti, who had never had any experience

with heart disease, thought at first that he was exaggerating the problem, but once she realized how serious his condition

was, she worried day and night about his health and threw all her nervous energy into his recovery effort. In those days before

heart bypasses and angioplasties, doctors prescribed rest and more rest for his angina pectoris and mild heart attack, if

that is what it was. Dr. Reitter was also given a variety of injections, but nothing seemed to help. Whenever I went to visit

him, we would talk about his recovery prospects, which he felt were increasingly less promising. From time to time, he would

draw a picture of the inside of his heart and show me where his blood vessels appeared to be blocked and why his heart did

not get the blood it needed. Once in a while, when a nurse was very busy, he would show me how to give him an injection he

needed — it was usually morphine — and I became quite good at dispensing it. Increasingly, though, he was getting weaker,

particularly as water began to accumulate in his lungs and had to be drawn out with greater frequency. Then one day he told

me that he would soon die and that it would be up to me to take good care of Mutti. But I was not to tell Mutti that the end

was near. Not long after our conversation, Dr. Reitter died peacefully in his sleep. This was the second time I had lost a

father and Mutti a husband. At that point we both decided that there was no God in heaven, for what kind of God would permit

such a good man to die so young — he was only forty-eight years old — and cause so much suffering to be visited on one small

family?

Dr. Leon Reitter, 1947

It took Mutti and me a long time to get over Dr. Reitter’s death, if we ever did. Her thyroid condition began to act up again

and with it her irregular heartbeat. We tried to console each other without much success, but we both knew that life had to

go on and that we had to make the best of it. Our daily routine was interrupted one afternoon by an event that brought some

happiness and excitement into our lives. Not long after I had arrived in Göttingen from Otwock, I told Mutti and Dr. Reitter

about the Norwegian who had helped me so much in the Sachsenhausen infirmary and who probably saved my life. Although I had

forgotten his name, I remembered that one day, when he brought me a jar of cookies he had received through the Swedish Red

Cross, he pointed to the picture of a man on the side of the jar and said that it was his father. When Mutti heard my cookie-jar

story, she suggested that the man whose son I knew in Sachsenhausen probably was a cookie manufacturer and that it was most

unlikely that I would ever find him. But then, sometime in early 1948, Mutti saw an article in a newsletter published by an

organization of former concentration camp inmates. The article reported that a Norwegian by the name of Odd Nansen, son of

the famous Norwegian explorer and statesman Fridtjof Nansen, had recently published the diary he had kept in various camps

in Norway as well as in Sachsenhausen, and that it had become the most widely read book in Norway.

*

After showing me the article, Mutti suggested that I write the author of the book and ask whether he could help me find the

person who had been so kind to me in Sachsenhausen. I did just that. My letter to him began as follows:

Dear Mr. Nansen:

Please forgive me for disturbing you. A few days ago we read an article which pointed out that the most widely read book in

Norway was your diary about your three-year incarceration in Sachsenhausen. I was also in Sachsenhausen. My name is Tommy

Buergenthal, and I was ten years old at the time. I was in the

Revier,

where two of my toes were amputated.

Then I told him about the Norwegian I had met there, that he had been very kind to me and helped me very much, but that I

had forgotten his name and address. In the last paragraph of my letter, I reported that I had found my mother after a two-year

separation, and continued:

The name Nansen sounds most familiar to me, and that is why I am writing this letter to you. Could you possibly be that certain

person? In case you are not, I would like to ask you to inquire among your circle of friends who that person could have been

so that I might thank him.

Since I did not have the address of the author of the diaries, I simply addressed the letter to “Mr. Odd Nansen, Norway,”

and mailed it off.

Now the wait started. Weeks passed without an answer. In time I forgot all about the letter. Then one day our doorbell rang.

When I opened the door, I was greeted by a Norwegian soldier who had arrived in a Norwegian military truck. (At that time,

there was a small Norwegian military garrison stationed in the British Zone of Germany.) Pointing to the truck, he said that

he had a package to deliver. When I suggested that he give it to me, he said it was too big for me to carry. At that point,

two other soldiers jumped off the truck and opened its rear flap. They pulled out a huge wooden crate and carried it into

the house, up the stairs, and into our apartment. “This is from Odd Nansen,” one of the soldiers said, as he handed me a letter.

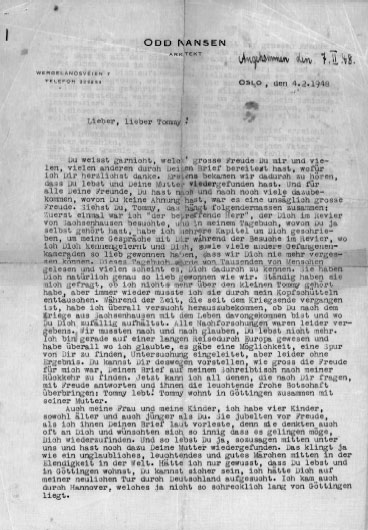

The letter began with “

Lieber, lieber

Tommy!” And it continued:

You cannot imagine the great happiness your letter produced in me and many, many others.…That is how we learned for the first

time that you were alive and had found your mother. Your letter made your many old friends very happy, as well as the many

new friends you now have without knowing it.…First, I have to tell you that I am “that certain person” who visited you in

the

Revier

in Sachsenhausen. Moreover, in my diaries, which you already know about, I devote a number of chapters to you and to our

conversations in the

Revier,

where I met you and where I and many of my comrades came to love you and could never forget you. Many thousands of people

have now read my diaries, and many of them think they know you because of that book. They have frequently asked me whether

I had heard anything about little Tommy, but again and again I had to disappoint them.

Mr. Nansen then told me of his long and unsuccessful search for me, and his gradual assumption that I had not survived. But

my letter changed all that. To know that I was alive and that I had been reunited with my mother was marvelous news for him,

his family, and my many old and new friends. He asked me to write right away and to tell him all about myself and my mother

and whether I had found my father. He also wanted to know whether we needed anything, particularly food and clothing, and

he offered to help us move to Norway, where living conditions at the time were better than in Germany. The letter was signed,

“Your ‘Uncle’ Odd (Nansen).”