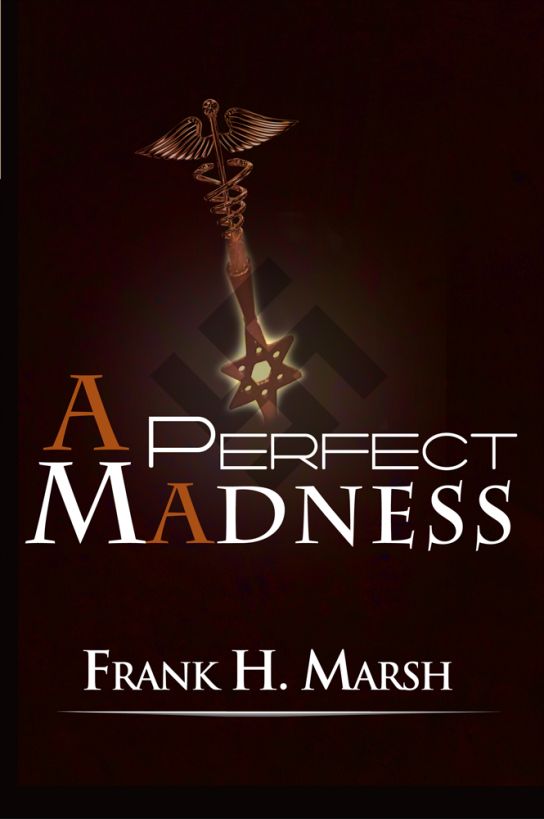

A Perfect Madness

Authors: Frank H. Marsh

Tags: #romance, #world war ii, #love story, #nazi, #prague, #holocaust, #hitler, #jewish, #eugenics

A Perfect Madness

A novel

By Frank H. Marsh

Published by Brandylane Publishers at

Smashwords

Print copies available at

http://www.brandylanepublishers.com

Copyright 2012 by Frank H. Marsh.

This book is a work of historical fiction.

References to real people, events, places, and establishments are

done so to provide a sense of authenticity to the story. All other

characters, and all incidents and dialogue, are drawn from the

author’s imagination and are not to be construed as

real.

Smashwords Edition, License

Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal

enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to

other people. If you would like to share this book with another

person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If

you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not

purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com

and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work

of this author.

***

For my dear deceased friend,

Dr. David L. Dungan

***

“There is a divinity that shapes our

ends,

Rough hew them how we will.”

(Hamlet, V, ii, 10)

***

ONE

Prague, 1992

I

t wasn’t Anna’s idea

to take Julia’s ashes back to her beloved Prague. She would have

sprinkled them up and down the banks of the Merrimack River running

the rear property line on their small farm outside Franklin, New

Hampshire. It was a God-given place to Julia for sure, as still and

reverent as any cemetery except for the flowing sounds of the

passing waters, which she loved. To have done so, though, meant

betraying the only real promise she had ever made to her mother, a

promise crammed full with the final chapters of a long odyssey her

mother began years back, in 1939, when Prague found itself standing

naked with all of Europe in a gathering storm of madness. So

Julia’s ashes would be buried soon where they should be, next to

Rabbi Loew’s grave in the Old Jewish Cemetery, even though no new

soul had been allowed to rest there in over two hundred years.

The promise, strange as it was to

become, came from Anna the year before Julia died. Following the

Velvet Revolution, Prague had quickly beckoned all that was good to

come home again to the old city. So they went there together, Anna

and Julia—Anna out of curiosity, or better, perhaps, from the

metaphysical tugging of ancient kin long dead and buried there,

Julia to find the lost innocence of her youth buried along with her

heart somewhere beneath a rubble of trampled dreams fifty-two years

earlier. The dreams would still be there waiting, she would tell

Anna during one of her many stories, scattered along the cobbled

brick streets in the old Jewish quarters. But she was dying now at

seventy-four. A doctor herself, Julia knew the end was near, so the

promise given by Anna was all she really had left.

When their plane began circling the

great city that day, waiting to land, the special moment came. At

first Julia sat silent, looking down on the vast carpet of

red-tiled roofs covering the city, wondering if distant memories of

magical places and golden dreams would betray her. Stories she had

told Anna many times were there waiting. It was then that the

strange promise was pulled from Anna’s lips by Julia. When death

came to her, wherever it might be, Anna was to somehow smuggle her

remains into the Old Jewish Cemetery. There she was to dig a small,

shallow hole alongside the great Maharal Rabbi Loew’s grave, where

God stayed close, and bury her ashes. For Julia it was the

necessary place, the place where many of her childhood dreams had

played out. She would go there to talk with Rabbi Loew and his

gentle golem, called Josef, about the struggles of her people and

the madness in her own life. No one else would be there except

those that danced and played in her imaginary world, and that was

good enough for her. Rabbi Loew and his golem were legends then—and

her friends. Sooner or later, she believed, they would come to her,

stepping out of the misty stillness covering the graves, and listen

to her cries.

One afternoon late, she decided to try

and make another golem, one she could see and touch and of the

female gender. Following the instructions in her father’s tomes on

Jewish mysticism, she set out to complete the task. Carrying

buckets of wet clay dug from the banks of the Vltava River to the

cemetery, she fashioned the form of a woman alongside the rabbi’s

grave, three cubits long, lying on her back, and then shaped a face

and arms and legs. Then she walked around her golem six times, the

days God took to create the world, reciting loudly various

combinations of words she had pulled from the Book of Genesis. But

the mud-shaped golem stayed still and quiet, like Josef. After

chanting new combinations of words and walking around her golem

many more times with no result, Julia decided that the secret to

life was where it should be, with Rabbi Loew. And she was glad,

because he was her friend.

After they had landed and were

departing from the airport, Julia cried, “We must hurry to the

cemetery now before the luggage is unpacked. The ringing of hand

bells will start soon, telling everyone to leave.”

The skies over Prague had turned to a

gray dusk by the time Anna and Julia arrived at the historical gate

that separates one’s existence from eternity, a place where, for a

brief moment, the ends of time come together and become

one.

“

Hurry,” Julia

urged.

Anna stood still, though, trapped in a

timeless zone, gazing through the open gate at the crowded graves

squeezed together in the small plot, their headstones looking like

so many crooked and jagged teeth. There were no clear rows before

her, only confusion. Over 100,000 souls layered twelve deep in

their graves, all yielding in turn their identity to the top tier

of buried bodies. Yet the totality of each grave clung silently

persistent to its own tiny share of a thousand years of the Jew in

Prague.

“

Which one is Rabbi Loew’s

grave?” Anna asked, unable to distinguish any clearly marked

headstone.

“

Look closely, there

towards the middle,” Julia responded excitedly.

Anna had missed it at first, but then

she saw a blackened and weathered headstone with coins and pebbles

strewn out before it, some resting on bits of folded

paper.

“

Rabbi Judah Loew ben

Balazel. 1520-1609.”

“

Yes! Yes!” Julia shouted,

making her way slowly through an army of tall headstones circling

the good rabbi’s grave like concrete sentinels.

“

Why the rocks and paper?”

Anna asked, reaching down to pick up a small yellow note faded by

time.

“

No, don’t! They are

private prayers to Rabbi Loew asking for help or advice. It would

be like listening in on someone’s confession.”

“

I suppose some were

answered?” Anna said, trying hard to share this special moment with

her mother.

Julia knelt down and gently traced her

fingers across the rabbi’s headstone.

“

Maybe, but mine

weren’t.”

“

You left messages

too?”

“

Oh yes, many. The last

two on the day before my brother Hiram and I left for England. The

Nazis had begun closing all roads to the city then. I asked that

Papa and Mama would soon follow. But they didn’t,” Julia murmured,

her voice trailing off to a whisper.

“

And the other

note?”

“

To my precious Erich,

about whom I have told you many stories. I was sure we would meet

again someday when the world came to its senses, and be married. It

was very romantic.”

“

Did Erich believe in the

golem?

“

I don’t know. I think

maybe he believed because I did. I told him, if Rabbi Loew made the

golem, then he had to have a direct line to God. That’s why so many

people left their prayers and wishes with the good rabbi, and still

do. He was seen as a Jewish savior by many. But Papa always got too

intellectual when I talked about the golem, said he was like the

good fairy. I know Erich agreed with him, because he said many

Germans saw their ancient warriors as still alive, but he wouldn’t

say he did.”

Anna looked tenderly at Julia and the

tears forming in her eyes as she continued talking about Erich. How

old she looked at seventy-four, stooped and wrinkled all over. Time

had not been gentle to her. She often referred to herself as a

lonely woman—she would call it that loneliness that is so hard on

the young, but so sweet to the old—and in a sense that was true.

Only an occasional twinkle in her eyes gave hint to the joy she

once held for simply being alive. No one had danced through life to

so many different tunes as she had. She gave so much, it seemed

like all of nature borrowed life from her. Blessed with an

insatiable curiosity about the way the world worked, she would

spend her Sundays around Old Town, simply watching life happen. So

intimate and passionate was her love of life, she seemed a part of

every living thing. There wasn’t one thing about living she didn’t

like, because it was a one-time affair. She knew that when it was

over, it was over. But now she had become obsessed with death and

the journey her soul would take when it came.

“

How often would you come

here?” Anna asked, still mystified by the rabbi’s grave.

“

Once a week, maybe. I

tried to come every day, though, after the Sudetenland was annexed

by Germany. It was one of the few places where Jews were not spit

on.”

“

With Erich?”

“

Oh yes, with Erich. Many

times we were here together. Especially when darkness came and the

city was quiet.”

“

You made love in a

cemetery?” Anna asked, grinning, amazed at such a revelation from

her mother.

“

Certainly. It was funny,

though, that when we first would come here and lay together, he was

very shy, thinking for a long time we were being watched. But I

told him the golem was asexual and cared little about what we were

doing. What was important to him was that we were in love,” Julia

said, laughing loudly before continuing.

“

We came unashamedly at

first, then secretly until I left and he was to return to Dresden.

When the final hour came for separation, there were no more words

to say. I left my prayer with the rabbi and walked home alone. We

both vowed, though, that our love would stay here with Rabbi Loew’s

grave until we were together again.”

“

We should go to Dresden

while we’re this close; perhaps he is still alive and living there.

What a surprise that would be,” Anna said teasingly.

Julia frowned and turned away, yet

Anna’s words had quickened her dying heart. She had left him here,

standing alone by the gate after their last moments together. Now,

fifty-two years later, all she could recall about him was the

warmth of his body. Nothing more. Not even the outlines of his

face.

Before she could respond to Anna’s

jesting words, the caretaker began walking among the headstones

ringing a hand bell like a town crier of old.

“

You know now what you

must do when I die, and where,” Julia said, quickly pointing once

more to Rabbi Loew’s grave. “Now we must hurry into the Pinkas

Synagogue before they close the doors. Papa and Mama will be

there.”

Julia and Anna walked a few paces from

the cemetery gate to a small courtyard fenced around a side

entrance to the synagogue and stepped inside the door. Neither one

was prepared for what followed. With each step they took, silent

voices from thousands of faceless victims reached out to them from

behind the countless rows of names spread across every inch of the

synagogue’s stone walls. All that they were and ever would be was

there, squeezed into each letter of their names. This was all any

of us would ever know about them, Julia knew. Yet each name knew

the others. They had all walked the same road to their deaths.

Looking around, Julia believed there was no place on earth large

enough to contain so much sorrow staring back at her from the

eighty thousand names spread across the walls.