A Place Called Armageddon (2 page)

Read A Place Called Armageddon Online

Authors: C. C. Humphreys

Don Francisco de Toledo, Castilian soldier

John of Dalmata, imperial councillor

Archbishop Leonard

Cardinal Isidore

Radu Dracula

The Man with Long Sight

Ulvikul, cat

To the Reader

…

A city’s fall is rarely as sudden as Pompeii’s. Like an old man tottering on a precipice, it is a long decline that has brought him to the edge.

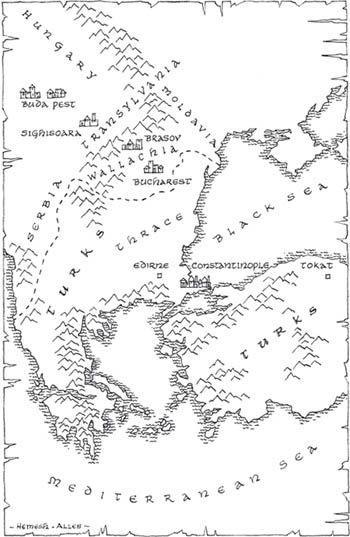

In 1453, such a city is Constantinople.

Blessed by geography, straddling the continents of Europe and Asia and the most important trade routes on earth, Constantinople and its Byzantine Empire had thrived, at one time controlling two-thirds of the civilised world.

Yet a thousand years of wars – foreign, civil, religious – has sapped its strength. Other Christians plundered it. The great powers of Venice and Genoa colonised it. By the mid-fifteenth century, the empire consists of little more than the impoverished city itself. Now, with doom approaching, those fellow Christians will only send help for an unthinkable price – the city has to give up its Orthodox Christianity and unite as Catholics under the Pope.

While the people riot, the emperor has no choice but to agree. Because he accepts what they do not.

The Turks are coming.

The Prophet foretold Constantinople’s fall to jihad. Yet for eight centuries, the armies of Allah have broken themselves on the city’s unbreachable walls. Even Eyoub, Muhammad’s own standard-bearer, died before them.

Then a young man picks up the banner. Determined to be the new Alexander, the new Caesar, Mehmet, sultan of all the Turks, is just twenty-one years old.

The old man totters on the precipice … and prays that he has not given up his faith in vain. Prays for a miracle.

PROLOGUS

6 April 1453

We are coming, Greek.

Climb your highest tower, along those magnificent walls. They have kept you safe for a thousand years. Resisted every one of our attacks. Before them, where your fields and vineyards once stood, are trenches and emplacements. Empty, for now. Do you expect them to be filled with another doomed army of Islam, like all the martyrs that came and failed here before?

No. For we are different this time. There are more of us, yes. But there is something else. We have brought something else.

Close your eyes. You will hear us before you see us. We always arrive with a fanfare. We are people who like a noise. And that deep thumping, the one that starts from beyond the ridge and runs over our trenches, through the ghosts of your vineyards, rising through stone to tickle your feet? That is a drum, a

kos

drum, a giant belly to the giant man who beats it. There is another … no, not just one. Not fifty. More. These come with the shriek of the pipe, the sevennote

sevre

, seven to each drum.

The

mehter

bands come marching over the ridge line, sunlight sparkling on instruments inlaid with silver, off swaying brocade tassels. You blink, and then you wonder: there are thousands of them. Thousands. And these do not even carry weapons.

Those with weapons come next.

First the Rumelian division. Years ago, when you were already too weak to stop us, we bypassed your walls, conquered the lands beyond them to the north. Their peoples are our soldiers now – Vlachs, Serbs, Bulgars, Albanians. You squint against the light, wishing you did not see, hoping the blur does not conceal – but it does! – the thousands that are there, the men on horseback followed by many more on foot. Many, many more.

The men of Rumelia pass over the ridge and swing north towards the Golden Horn. When the first of them reach its waters, they halt, turn, settle. Rank on rank on the ridgeline, numberless as ants. Their

mehter

bands sound a last peal of notes, a last volley of drumbeats. Then all is silent.

Only for a moment. Drums again, louder if that were possible, even more trumpets. Because the Anatolian division is larger. Can you believe it? That as many men pass over the hilltop again and then just keep coming? They head to the other sea, south towards Marmara, warriors from the heartland of Turkey. The

sipahi

, knights mailed from neck to knee, with metal turban helms, commanding their mounts with a squeeze of thigh and a grunt, leaving hands free to hoist their war lances high, lift their great curving bows. Eventually they pass, and then behind them march the

yayas

, the peasant soldiers, armoured by the lords they follow, trained by them, hefting their spears, their great shields.

When at last the vast body reaches the water, they turn to face you, double-ranked. Music ceases. A breeze snaps the pennants. Horses toss their heads and snort. No man speaks. Yet there is still a space between the vast divisions of Rumelia and Anatolia. The gap concerns you – for you know it is to be filled.

It is – by a horde, as many as each of those who came before. These do not come with music. But they come screaming. They pour down, and run each way along the armoured fronts of Anatolia and Rumelia. They do not march. They have never been shown how. For these are

bashibazouks

, irregulars recruited from the fields of empire and the slums of cities. They are not armoured, though many have shields and each warrior a blade. Some come for God – but all for gold. Your gold, Greek. They have been told that your city is cobbled with it, and these tens of thousands will hurl themselves again and again against your walls to get it. When they die by the score – as they will – a score replaces them. Another. Each score will kill a few of you. Until it is time for the trained and armoured men to use their sacrificed bodies as bridges and kill the few of you who remain.

The horde runs, yelling, along the ordered ranks, on and on. When at last it halts, even these men fall quiet. Stay so for what seems an age. And that gap is still there, and now you almost yearn for it to be filled. Yearn too for the hush, more dreadful than all those screams, to end. So that this all ends.

And then they come. No drums. No pipes. As silent as the tread of so many can be.

You have heard of them, these warriors. Taken as Christian boys, trained from childhood in arms and in Allah, praise Him. Devoted to their corps, their comrades, their sultan. They march in their

ortas

, a hundred men to each one.

The janissaries have arrived.

You know their stories, these elite of the elite that have shattered Christendom’s armies again and again. In recent memory alone, at Kossovo Pol, and at Varna. As they swagger down the hill, beneath their tall white felt hats, their bronzed shields, their drawn scimitars, their breastplates dazzle with reflected sunlight.

They turn to face you, joining the whole of our army in an unbroken line from sea to sparkling sea. Again a silence comes. But not for long this time. They are waiting, as you are. Waiting for him.

He comes. Even among so many he is hard to miss, the tall young man on the huge white horse. Yet if you did not recognise him, you will by what follows him. Two poles. What hangs from one is so old, its green has turned black with the years. It looks to you what it is – a tattered piece of cloth.

It is the banner that was carried before the Prophet himself, peace be unto him. You know this, because when it is driven into the ground, a moan goes through the army. And then the second pole is placed and the moan blends with the chime of a thousand tiny bells. The breeze also lifts the horsetails that dangle from its height.

Nine horsetails. As befits a sultan’s tug.

Mehmet. Lord of lords of this world. King of believers and unbelievers. Emperor of East and West. Sultan of Rum. He has many titles more yet he craves only one. He would be ‘Fatih’.

The Conqueror.

He turns and regards all those he has gathered to this spot to do his and Allah’s will. Then his eyes turn to you. To the tower where you stand. He raises a hand, lets it fall. The janissaries part and reveal what you’d almost forgotten – that square of dug earth right opposite you, a medium bowshot away. It was empty when last you looked. But you were distracted by innumerable men. Now it is full.

Remember I told you we were bringing something different? Not only this vast army. Something new? Here it is.

A cannon. No, not a cannon. That is like calling paradise ‘a place’. This cannon is monstrous. And as befits it, it has a monster’s name. The Basilisk. It is the biggest gun that has ever been made. Five tall janissaries could lie along its length. The largest of them could not circle its bronze mouth in his arms.

Breathe, Greek! You have time. It will be days before the monster is ready to fire its ball bigger than a wine barrel. Yet once it begins, it will keep firing until … until that tower you stand on is rubble.

When it is, I will come.

For I am the Turk. I come on the bare feet of the farmer, the armoured boot of the Anatolian. In the mad dash of the

serdengecti

who craves death and in the measured tread of the janissary who knows a hundred ways to deal it. I clutch scimitar, scythe and spear, my fingers pull back bowstring and trigger, I have a glowing match to lower into a monster’s belly and make it spit out hell.

I am the Turk. There are a hundred thousand of me. And I am here to take your city.

–

PART ONE

–

Alpha

–

ONE

–

Prophecy

Edirne, capital of the Ottoman Empire

April 1452: one year earlier

The house looked little different from any other that faced the river. A merchant’s dwelling, its front wall was punctured by two large square openings either side of an oaken door. These had grilles to keep out intruders, while admitting the water-cooled breezes that would temper the summer heat.

Yet this was early April, the openings were shuttered and Hamza shivered. Though it was not truly the chill that caused his skin to stand up in bumps. It was the midnight hour. It was their reason for standing there. It was this house, especially.

‘Is this the place, lo—’ He cut himself off. Even though the two men were obviously quite alone, they were not to speak their titles aloud. ‘Erol’ his younger companion wished to be called, a name that told of courage and strength. Hamza had submitted to ‘Margrub’. He knew it meant ‘desirable’. The young man had insisted on it with a smile because he did not find Hamza desirable in the least.

Undesired but useful. It was why he had insisted that only Hamza accompany him to the notorious docks of Edirne, where merchants built their houses into forts and men of sense travelled in large, well-armed groups. He hadn’t been brought for his bodyguard skills, though he was as adept as most with the blade he concealed beneath his robes. It was his mind the younger man needed.

‘Come,’ he’d said. ‘Allah is our bodyguard.

Inshallah

.’

Now, at their destination, the reply to Hamza’s query was a gesture. He lifted the lamp he carried, opened the gate on it, held it high. His companion peered up beside the door. ‘Yes, this is the one. See!’

Hamza looked. There, nailed to the frame beside the door, was a wooden tube, smaller than his little finger. He knew what it was, what it contained. He lowered the lamp, closed the gate, returning them to near darkness and river mist. ‘You did not tell me she was a Jewess.’

He could not see it but he could hear the smile in the reply. ‘All the best ones are. Knock!’

His knuckle had barely struck a second time before a small gate in the doorway was opened. They were studied, the small door closed, the larger one unbolted. They were admitted by someone who remained hidden in the darkness behind the door. ‘Straight ahead … friends,’ ordered a soft male voice, and they obeyed, moved into the roofless courtyard beyond, blinking against its sudden light, for reed torches burned in brackets, flame-light spilling onto a garden, four beds of earth around a central fountain.