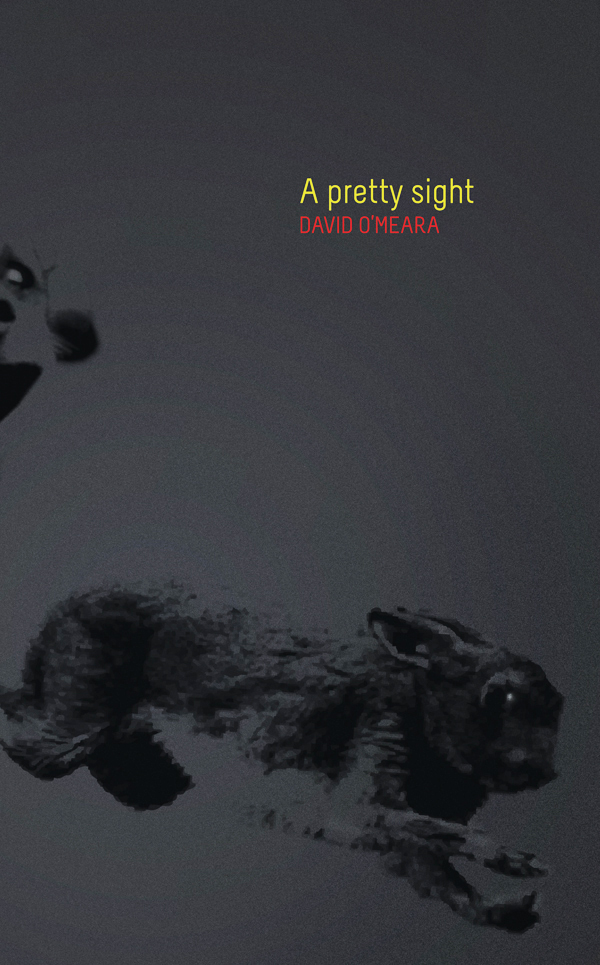

A Pretty Sight

Authors: David O'Meara

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Poetry, #World Literature

Copyright © David O'Meara, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,

recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the internet or any other

means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do

not participate in electronic piracy of copyright material; purchase

only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the

author's rights.

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the

Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Coach House Books also

acknowledges the support of the Government of Canada through the

Canada Book Fund and the Government of Ontario through the

Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in publication

O'Meara, David, 1968-, author

A pretty sight / David O'Meara.

Poems.

eISBN 978-1-77056-359-9

I. Title.

PS8579.M359P74 2013 cC811′.54 C2013-904124-9

For Dorothy

Wood warps.

Glass cracks.

The whole estate

goes for a song.

The cardboard

we used

to box up the sun

didn’t last long.

- Occasional

- Background Noise

- Socrates at Delium

- The Afterlives of Hans and Sophie Scholl

- Vicious

- Dance

- Umbrage

- Drought Journal

- Terms

- Hare

- Memento Mori

- Circa Now

- ‘In Event of Moon Disaster’

- In Kosovo

- Ten Years

- The Tennis Courts in Winter

- So Far, So Stupid

- Somewhere, Nowhere

- No One

- Reclining Figures

- Loot

- Impagliato

- Talk

- Silkworms

- ‘There’s Where the American Helicopters Landed’

- End Times

- Sing Song

- How I Wrote

- Memento Mori

- Charles ‘Old Hoss’ Radbourn, 1886

- Fruit Fly

- Close All Tabs

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

As Poet Laureate of the Moon

I’d like to welcome you

to the opening of the Armstrong Centre

for the Performing Arts. I was asked to prepare

a special verse to mark

this important occasion. And I’d be the first

to confess: the assignment

stumped me. Glancing around my workspace’s

dials and gauges, and the moonscape

through triple hermetic Plexiglas,

I struggled to settle on the proper content

to hard-text into the glow of my thought-screen.

In the progress of art and literature, the moon’s

been as constant a theme as rivers or the glare

of the sun, though even after several bowls

of potent plum wine, a T’ang poet would never

have guessed, addressing this satellite across

the darkness, that someone would ever write back.

The Centre itself, I know, isn’t much;

a duct-lined node bolted to the laboratory,

powered by sectional solar panels mounted

on trusses, parked not far from the first

Apollo landing. We live with bare minimum:

cramped, nutrient-deprived, atrophying

like versions of our perishables

in vacuum-pack. The lack’s made my sleep

more vivid. Last night I dreamt I was in

a pool where cattle hydrated, then

fell tenderly apart in perfect lops of meat.

(I see a few of you nodding there in the back.)

So what good will one room do us? Maybe

none. Maybe this streamlined aluminum

will become our Lascaux, discovered by aliens

ages hence, pressing them to wonder what

our rituals meant, what they said of our hopes and fears.

Somewhere in this lunar grind, in the cratered gap

between survival and any outside meaning,

must be the clue to our humanity, the way

Camus once argued the trouble for Sisyphus

wasn’t the endless failure to prop

a rock atop some hill, but the thoughts

he had on the way back down.

Which brings me to the astronauts of Apollo 11.

After snapping the horizon through the lens

of a single Hasselblad, knowing every boot tread

they left was eternal, they’d squeezed

through the hatch of their landing module, shut

and resealed it for return to Earth,

then discovered, due to cramped space

and the bulk of their spacesuits, they’d crushed

the switch for the ascent engine. The rockets failed

to activate. So Buzz Aldrin used part of a pen

to trigger the damaged breaker, toggling until

it fired the sequence for launch. This

was the quiet work of his engineer’s mind.

He kept the pen for the rest of his years,

which is another kind of thinking, akin to

that

slight pivoting

, as Camus would call it,

when we glance backward over our lives.

What we keep in the pause between facts

might be the beginning of art. Which is where

we are in this room tonight. I’ll have to stop there;

the teleprompter is flashing for wrap-up. Following

tonight’s program, I’m happy to announce

an extra ration of Natural Form and

H2O

will be served by the airlock. I think

you’re in for quite a show. So hold on

to your flight diapers as we cue the dancers

who’ve timed their performance to the backdrop

of Earthrise. There it is now in the tinted

north viewpoint. Look at that, folks. To think

they still find bones of dinosaurs there.

Home, my coat just off, the back room

murky and static, like the side altar of a church, so at first

I don’t know what I hear:

one low, sustained, electronic note

keening across my ear. I spot

the stereo glow, on all morning, the cd

at rest since its final track, just empty signal now,

an electromagnetic aria of frequency backed

by the wall clock’s whirr, the dryer droning in the basement,

wind, a lawn mower, the rev and hum of rush hour

pushing down the parkway. I hit the panel’s power button,

pull the plug on clock and fridge, throw some switches,

trip the main breaker, position fluorescent cones to stop traffic.

Still that singing at the edge of things.

I slash overhead power lines, bleed the radiator dry,

lower flags, strangle the cat

so nothing buzzes, knocks, snaps or cries.

I lock the factories, ban mass

gatherings, building projects and roadwork,

any hobbies that require scissors, shears, knitting needles, cheers,

chopping blocks, drums or power saws. It’s not enough.

I staple streets with rows of egg cartons. I close

the airports, sabotage wind farms, lobby

for cotton wool to be installed on every coast. No luck.

I build a six-metre-wide horn-shaped antenna, climb

the gantry to the control tower, and listen in.

I pick up eras of news reports, Motown, Vera Lynn,

Hockey

Night in Canada

, attempt to eliminate all interference,

pulsing heat or cooing pigeons, and yet there it is:

that bass, uniform, residual hum from all directions,

no single radio source but a resonance left over

from the beginning of the universe. Does it mean

I’m getting closer or further away? It helps to know

whether we’re particle, wave or string, if time

and distance expand or circle, which is why

I need to learn to listen, even while I’m listening.

What do I know? At least these

last two mornings since the Boeotian

ranks massed. The whole lot of us

had been camped inside their border, sea

at our backs. We thought we’d soon

be home in Athens. A set of cooking fires

still smoked behind the earthworks, evidence

of a hurried defence at the temple we’d occupied,

an obvious insult. The old seer took

the ram and made a lattice of its throat,

our counter-prayer

for the terror we hoped to inspire.

Across the dawn fields, the enemy trod

through the stripped orchards and wheat,

farmers like us, setting out cold in linen

and cloaks, the well-to-do armoured

for glory out front. After weeks of marching,

the suddenness of it: the general’s shouts,

his interrupted speech passed down the lines,

our pipe marking the pace, and far off,

their war cry rending the November air

like a thousand sickles. The black doors

of each empty farmhouse watched our lines

clatter through stubbled stalks,

my arm already heavy from the shield.

‘Stay tight, stay tight,’ we called across

the bronze rims, cursing and half out of breath.

Then a new shout went out

and we spilled up the ridge at a run

into the Thebans’ spear thrusts.

In the push, there’s little room for a view;

dust scuffed up by thousands of men

gagged the air. Best to trust in detail,

watch for sharp jabs at your throat,

stay flush with the column, and above all else

don’t fall. Not so easy with the friendly shields

pressing behind, and reaped furrows

snatching your balance. Our phalanx

held, shoving, and forced the Thebans

back over ground they’d claimed at midday.

But there was a too-easy feel to it,

as if we expected they’d break, and we’d slide

through their lines like lava from Hades.

Word spread of horsemen on the hill.

A trick? Who knew? We were servants

to rumour. A few turned and ran,

then the rest. Then I did too.

‘Don’t show them your backs,’ I cried

to a group, shopkeepers from the look

of them. ‘Do you want wounds

there

when your corpse is exchanged?’

That turned them around.

We still had our swords. Scavenging cracked

spear-lengths to keep the cavalry off,

we backpedalled over corpses, boulders

and olive roots into dusk. That was two days ago.

More rumours follow us to Attica: Hippocrates

dead, how we were outnumbered,

whispers of the slaughter chittering in our ears

like broken cart wheels. Though we know the direction

home, we stall, not from plague that still strays

in its streets, but the shame of retreat.

Night, the cooking fires again.

We who are left, battered stragglers, scoop gruel

and wait for orders to seek out our dead.

Now, on the edge of the firelight, a rhapsode

recites an ancient passage, his voice recalling Troy,

the dark-beaked ships and grief for Patroclus.

We were brave enough, but couldn’t hold.

What use is a story or a song?