A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (43 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

Human rights groups were quicker than they had ever been to document atrocities. Helsinki Watch, the European arm of what would become known as Human Rights Watch, had begun dispatching field missions to the Balkans in 1991.When the war in Bosnia broke out in 1992, the organization was thus able to call quickly on a team of experienced lawyers. In the early months of the war, Helsinki Watch sent two teams to the Balkans, the first from March 19 to April 28, 1992, the second from May 29 to June 19. Investigators interviewed refugees, government officials, combatants, Western diplomats, relief officials, and journalists. Aryeh Neier, executive director of Helsinki Watch, edited the impressive 359-page report, which contained gruesome details of a systematic slaughter. Neier found himself presiding over an organization-wide debate over whether the Serb atrocities amounted to genocide.

Neier had moved to the United States from Germany at age eleven as a refugee after World War II. As president of the history club at Stuyvesant High School in NewYork City, he had heard about the exploits of a fellow refugee, Raphael Lemkin, who had coined a new word. In 1952, forty years before the Bosnian war, Neier, a presumptuous sixteen-year-old, rode the subway to the new UN headquarters and tracked down Lemkin in one of its unused offices. Neier asked the crusader if he would come to speak to the Stuyvesant history club some afternoon. Never one to turn down a speaking engagement, Lemkin agreed, giving the future founder of Helsinki Watch his first introduction to the concept of genocide.

In the Helsinki Watch report, published just four months into the war in August 1992, the organization found that the systematic executions, expulsions, and indiscriminate shelling attacks at the very least offered "prima facie evidence that genocide is taking place." Neier had learned Lemkin's lessons well. The report said:"Genocide is the most unspeakable crime in the lexi con.... The authorization that the Convention provides to the United Nations to prevent and suppress this crime carries with it an obligation to act. The only guidance the Convention provides as to the manner of action is that it should be `appropriate' We interpret this as meaning it should be effective.""'

Helsinki Watch had a mandate different from that of Amnesty International. It criticized both the perpetrator state and the Western powers that were doing so little to curb the killing. But for all of their outrage, many individuals within the organization were uncomfortable appealing to the United States to use armed force. "We were in a real bind," Neier remembers. "The organization had never called for military intervention, and we couldn't bring ourselves to do so.Yet we could also see that the atrocities would not be stopped by any other means. What we ended up with was a kind of tortured compromise" In the report Helsinki Watch described U.S. policy as "inert, inconsistent and misguided"" It became the first organization to call upon the United Nations to set up an international war crimes tribunal to prosecute those responsible for these crimes. But when it came to the question of military intervention, it punted:

It is beyond the competence of Helsinki Watch to determine all the steps that may be required to prevent and suppress the crime of genocide. It may be necessary for the United Nations to employ military force to that end. It is not the province of Helsinki Watch to determine whether such force is required. Helsinki Watch believes that it is the responsibility of the Security Council to address this question."

The Security Council was made up of countries, including the United States, steadfastly opposed to using armed force.

A U.S. Policy of Disapproval

When Yugoslavia had disintegrated in June 1991, European leaders claimed they had the authority, the strength, and the will to manage the country's collapse. Europeans had high hopes for the era of the Maastricht Treaty and the creation of a borderless continent that might eventually challenge U.S. economic and diplomatic supremacy. Jacques Poos, Luxembourg's foreign minister, proclaimed "If anyone can do anthing here, it is the EC. It is not the U.S. or the USSR or anyone else"" The United States happily stepped aside. "It was time to make the Europeans step up to the plate and show that they could act as a unified power," Secretary of State James Baker wrote later. "Yugoslavia was as good a first test as any."" Whatever the longterm promise of the European Union (EU), it was not long into the Balkan wars before European weaknesses were exposed. By the time of the Bosnian conflict in April 1992, most American decisionmakers had come to recognize that there was no "European" diplomacy to speak of. They were left asking, as Henry Kissinger had done, "What's Europe's phone number?" Yet anxious to avoid involvement themselves, they persisted in deferring to European leadership that was nonexistent.

U.S. and European officials adopted a diplomatic approach that yielded few dividends. Cyrus Vance, secretary of state under President Carter, and David Owen, a former British Labour Party leader, were appointed chairmen of a UN-EU negotiation process aimed at convincing the "warring parties" to settle their differences. But nationalist Serbs in Bosnia and Serbia were intent on resolving difference by eliminating it. The "peace process" became a handy stalling device. Condemnations were issued. U.S. diplomats warned Milosevic that the United States regarded his military support for rebel Bosnian Serbs with the "utmost gravity." But because warnings were not backed by meaningful threats, Milosevic either ignored them or dissembled. "For Milosevic the truth has a relative and instrumental rather than absolute value," the U.S. ambassador to Yugoslavia, Warren Zimmermann, observed. "If it serves his objectives, it is put to use; if not, it can be discarded."" Although Milosevic struck some as a habitual liar, most U.S. and European diplomats continued to meet his undiplomatic behavior with diplomatic house calls. Milosevic did not close off the diplomatic option as the Khmer Rouge had done. Instead, he shrewdly maintained contact with Western foreign servants, cultivating the impression from the very start of the conflict that peace was "right around the corner"

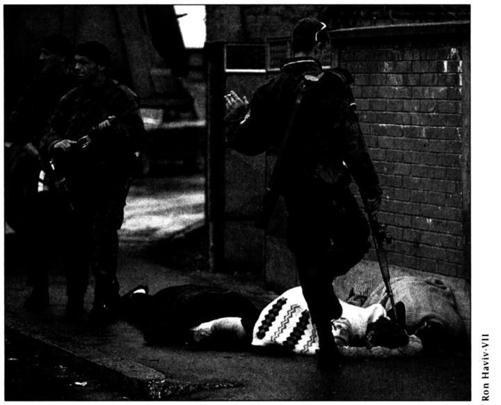

Serb Paramilitaries in Bijeljina, Bosnia, Spring 1992.

Most diplomats brought a gentlemen's bias to their diplomacy, trusting Milosevic's assurances.This was not new. Most notorious, Adolf Hitler persuaded Neville Chamberlain that he would not go to war if Britain and France would allow Germany to absorb the Sudetenland. Just after the September 1938 meeting, where the infamous Munich agreement was signed, Chamberlain wrote to his sister: "In spite of the hardness and ruthlessness, I thought I saw in his face, I got the impression that here was a man who could be relied upon when he gave his word"" When it came to Milosevic, Ambassador Zimmerman noted, "Many is the U.S. senator or congressman who has reeled out of his office exclaiming, `Why, he is not nearly as bad as I expected!""' Milosevic usually met U.S. protests with incredulous queries as to why the behavior of Bosnian Serbs in Bosnia had anything to do with the president of Serbia, a neighboring state. He saw that the Bush administration was prepared to isolate the Serbs and brand them pariahs but not intervene militarily. This the Serbian leader deemed an acceptable risk.

Washington's foreign policy specialists were divided about the U.S. role in the post-Cold War world. One camp believed in the idealistic promise of a new era.They felt that the Gulf War eventually fought against Saddam Hussein in 1991 and the subsequent creation of the safe haven for the Kurds of northern Iraq signaled a U.S. commitment to combating aggres- sion.Where vital American interests or cherished values were imperiled and where the risks were reasonable, the United States should act. They were heartened by Bush's claim that the GulfWar had "buried once and for all" America's Vietnam syndrome. The United States had a new credibility. "Because of what's happened," President Bush had said soon after the U.S. triumph, "I think when we say something that is objectively correct-like `don't take over a neighbor or you're going to bear some responsibility'people are going to listen." Still, for all the talk of a "new world order," Bush was in fact ambivalent. To be sure, the United States had made war against Iraq, a state that "took over a neighbor." But the United States had always frowned upon and occasionally even reversed aggression that affected U.S. strategic interests. Although Serbia's aggression against the internationally recognized state of Bosnia clearly made the Bosnian war an international conflict, top U.S. officials viewed it as a civil war. And it was still not clear whether the rights of individuals within states would have any higher claim to U.S. protection or promotion than they had for much of the century.

The other camp vying to place its stamp on the new world order was firm in the belief that abuses committed inside a country were not America's business. Most of the senior officials in the Bush administration, including Secretary of State Baker, Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney, National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell, were traditional foreign policy "realists." The United States did not have the most powerful military in the history of the world in order to undertake squishy, humanitarian "social work." Rather, the foreign policy team should focus on promoting a narrowly defined set of U.S. economic and security interests, expanding American markets, curbing nuclear proliferation, and maintaining military readiness. Although these were the same men who had waged the Gulf War, that war was fought in order to check Hussein's regional dominance and to maintain U.S. access to cheap oil. Similarly, when they established the safe haven for Kurds in Operation Provide Comfort, the Bush administration had been providing comfort to Turkey, a vital U.S. ally anxious to get rid of Iraqi Kurdish refugees.

With ethnic and civil conflict erupting left and right and sovereignty no longer the bar on U.S. intervention it had been in Morgenthau's day, Bush's foreign policy team saw that the United States would need to develop its own criteria for the use of military force. In 1984 President Reagan's defense secretary, Caspar Weinberger, had demanded that armed interven tion (1) be used only to protect the vital interests of the United States or its allies; (2) be carried out wholeheartedly, with the clear intention of winning; (3) be in pursuit of clearly defined political and military objectives; (4) be accompanied by widespread public and congressional support; and (5) be waged only as a last resort.'" Powell, chairman of the joint Chiefs, now resurrected this cautious military doctrine and amended it to require a "decisive" force and a clear "exit strategy."'" Iraq had eventually threatened U.S. oil supplies, whereas Yugoslavia's turmoil threatened no obvious U.S. national interests. The war was "tragic," but the stakes seemed wholly humanitarian. It met very few of the administration's criteria for intervention.

Several senior U.S. officials may have also been influenced by personal idiosyncrasies in their handling of the Bosnian war. Secretary Baker relied heavily on his deputy, Eagleburger, whose diagnosis may have stemmed, in the words of Zimmerman, from "understanding too much.- Knowing that Croatian president Tudjman was a fanatical nationalist and frustrated that the lovely Yugoslavia was being torn apart, Eagleburger seemed to adopt a kind of "pox on all their houses" attitude, which, according to several of his State Department colleagues, he fed Baker. This was not uncommon. Journalists and diplomats who had served time in Belgrade tended to bring aYugo-nostalgia for "brotherhood and unity" to their analysis, which made them more sympathetic to the alleged effort of Yugoslav forces to preserve the federation than toward the nationalistic, breakaway republics that seemed uncompromising. They were right that the leaders of Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia were inflexible, and Tudjman was in fact a fanatic. But however blighted, the leaders of the secessionist states clued into Milosevic's ruthlessness faster than anyone in the West. The repressive policies of the Serbian president left no place in Yugoslavia for non-Serbs.

An "action memorandum" sent to Deputy Secretary of State Eagleburger two weeks into the Bosnian war in April 1992 proposed a variety of detailed economic and diplomatic measures designed to isolate the Belgrade regime. Eagleburger's signature appears at the bottom of the document-beside the word "disapprove"" Critics of the Bush administration's response branded it a "policy of appeasement," but it might better be dubbed a "policy of disapproval," a phrase that testifies more accurately to the abundance of "soft" and "hard" intervention proposals that were raised and rejected.

U.S. policymakers had a number of options. Most made their way onto the editorial pages of the nation's major dailies. The United States might have demanded that the arms embargo be lifted against the Bosnian Muslims, making a persuasive case at the UN Security Council. "I completely agree with Mr. Bush's statement that American boys should not die for Bosnia," Bosnia's Muslim president Alija Izetbegovic said in early August 1992. "We have hundreds and thousands of able and willing men ready to fight, but unfortunately they have the disadvantage of being unarmed. We need weapons." The United States might have helped arm and train the Muslims, using its leverage to try to ensure the arms were used in conventional conflict and not against Serb or, later, Croat civilians. But President Bush was opposed to lifting the UN embargo. "There are enough arms there already," he said. "We've got to stop the killing some way, and I don't think it's enhanced by more and more [weapons] ." 22